A Year Ago, These Uvalde Kids Left School Early. They’re Haunted by What Happened Next

The Treviños have suffered from panic attacks & nightmares since a mass shooting a year ago this week left 19 of their schoolmates and 2 teachers dead

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This story was written by Uriel J. García and photographed by Evan L’Roy.

For 24/7 mental health support in English or Spanish, call the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s free help line at 800-662-4357. You can also reach a trained crisis counselor through the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by calling or texting 988.

UVALDE — At 7 a.m. on a Monday in February, Jessica Treviño, with squinty eyes, goes into her sons’ bedroom and in a low, raspy voice tells them to wake up. Eleven-year-old David James rolls out of bed, but 9-year-old Austin, the youngest of the four Treviño children, doesn’t move from the lower bunk bed.

The siblings get ready for school. David James grabs the car keys and starts the family’s black Ram 1500 truck for his mother.

Austin, who is still in bed covered by a blanket, tells his mother he doesn’t want to go to school.

“I can’t leave you by yourself,” Jessica, 40, tells him, leaning over his body as their fat bulldog, Chubs, tries to jump on the bed. “You have to go to school.”

Austin doesn’t move. The night before, the sound of police sirens woke him.

“It’s ’cause there were cop sounds last night so he’s kinda scared,” David James tells his mother.

It’s not the first time one of the children won’t go to school because something spooked them. And Jessica knows it won’t be the last.

Three of the four Treviño children were students at Robb Elementary on May 24, 2022, and were on campus for an awards ceremony as an 18-year-old with an AR-15 rifle approached the school.

That day, Jessica picked up David James, Austin and her now 12-year-old daughter, Illiaña, from the school about 11:30 a.m.

Jessica later found out that as she was driving off, the shooter had just walked into a classroom, killing two teachers and 19 students — including Illiaña’s best friend, a 10-year-old student in room 112, who was Illiaña’s defender when other children made fun of her.

A few days after the shooting, Jessica took Illiaña, whom she calls Nana, to Uvalde’s plaza to leave a teddy bear and flowers at a memorial for her friend. Suddenly, Illiaña’s heart began to race and she had trouble breathing. Jessica took her to the local hospital, which transferred her to an intensive care unit in San Antonio. The doctor there told Jessica that Illiaña was suffering cardiac arrest and her body shut down from acute stress. She was released after a week.

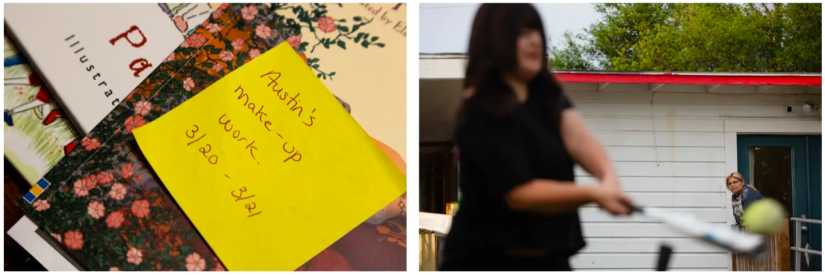

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/0418eb0da95df800f56fdb0d9b296669/0321-25 Trevino Family Week 2 23.jpg)

“Nana was born with a heart of gold,” Jessica says. “So when it breaks, that’s how she reacted.”

Now, things like the sound of police sirens, people yelling — just about any loud sound — can be triggers for Austin and Illiaña, who have developed post-traumatic stress disorder because of the shooting.

This morning, Jessica convinces Austin to get out of bed but agrees to let him miss school. She goes to the kitchen to get Illiaña’s antidepressant and anti-anxiety medicine from a lunch bag filled with prescription bottles. Then she hands Austin the pink ear protectors he uses to block out noise.

Austin says he puts them on “only when I hear the screams.”

Jessica said Austin’s therapist has told her that the kids may talk about the shooting like they were there in an unconscious attempt to empathize with the children they saw at school every day.

In the aftermath of the school shooting in Uvalde, much of the public’s attention has focused on the families of the children who died at Robb Elementary. Artists from San Antonio painted murals all over downtown memorializing the students and teachers who were killed. A year later, the city’s plaza is still adorned with crosses and photos of those who died.

The shooting has also caused emotional and psychological damage to a generation of Uvalde children, particularly the more than 500 students who attended Robb last spring. For the Treviño family, the shooting has reshaped their lives and influenced their children’s outlook on life. It has forced them to learn coping skills and learn how to be resilient.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/114bf30434c11afc7289121ea9abd4eb/0221-24 Trevino Family EL 03.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/8a61536ec1e3b946bbc2df432864a5d1/0221-24 Trevino Family EL 05.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/af90a62a3a8eaddd3363b7c68de382eb/A_009383-2.jpg)

Illiaña, David James and Austin barely escaped the horror their fellow students endured — hiding in their classrooms and hearing gunshots and the screams of terrified children. They each lost friends and classmates in the massacre and are dealing with that trauma in their own way.

Illiaña gets panic attacks, and David James and Austin have nightmares. Austin wets the bed at night and has accidents at school.

Illiaña and Austin are in therapy. So is the family’s oldest child, 13-year-old Ameliaña, who was in middle school last year and since the shooting has taken on the responsibility of helping to emotionally support her younger siblings. David James refuses to see a therapist.

Between 2018 and 2019, more than 100,000 American children attended a school where a shooting occurred, according to research co-authored by Maya Rossin-Slater, an associate professor at Stanford University School of Medicine.

“While many students are physically unharmed, studies have consistently found consequences to their mental health, educational, and economic trajectories that last for years, and potentially decades, to come,” Rossin-Slater wrote.

Most people “don’t think about the parents who had children who survived,” says David, Jessica’s husband. “All the costs that we have to pay for because of the shooting, like therapy and other things.”

Jessica says she gave the state-funded counseling at Uvalde’s new resiliency center a try for Illiaña but didn’t like its practice of rotating staff, which meant her daughter couldn’t see the same counselor at every visit.

Jessica takes a sip from the first of four cups of coffee she will drink today and swallows a tablet for her oral chemotherapy. She was diagnosed with breast cancer in November but opted not to undergo radiation treatment because she fears it would sap the last of her energy.

“I’m doing oral chemotherapy because otherwise I wouldn’t be able to take care of them,” Jessica says, motioning toward her children. “And as you can tell, it’s a job to take care of them.”

David, 42, stays in bed. He is paralyzed from the waist down, so it’s hard for him to help with the children in the mornings.

By 7:45 a.m., Jessica gets the four children in the truck and drops them off at their new schools: Illiaña, David James and Austin attend Sacred Heart, the local private Catholic school, while Ameliaña — an angsty teenager who’s easily annoyed by her mother’s advice — goes to Uvalde Classical Academy, a private high school. The Treviños hoped their kids would be safer at private schools and that maybe Illiaña wouldn’t face bullies.

After drop-offs, Jessica returns home with Austin, where she’ll spend the day with him until it’s time to pick them up again. She quit her job cleaning vacation cabins shortly after the shooting so she could be around her children as much as possible. Now they survive on David’s disability checks and Jessica’s dwindling savings.

David says he sometimes feels helpless, knowing that he doesn’t have the tools to help his children cope with the trauma the shooting has caused.

“It’s hard for me because I’m the type of man that if there’s anything in the way of my family’s happiness, I would move it out of the way,” he says. “But after [the shooting], there’s nothing to move out of the way, there’s nothing physically that I can do. It’s all mental. So that’s what makes it really hard for me.

“It’s just really hard because I know how my children were before the shooting.”

February 21

On a Tuesday evening, Jessica takes Illiaña and Ameliaña to a park near the edge of town for softball practice. The Treviños got all of the kids into basketball or softball after the shooting to help them stay busy. As her daughters join the other girls on the team, Jessica stands nearby, holding a can of Monster Energy drink. It helps offset the chemo pills, which make her lethargic.

A coach bats fly balls to the girls. Jessica looks on and laughs when she sees Illiaña, who is twirling and dancing in place on the field, entertaining herself. Jessica says Illiaña — a sassy preteen who enjoys drawing, reading Japanese comics and listening to rock music — joined the softball team mostly to spend time with her older sister, who takes the sport more seriously and dreams of playing on the Baylor University team.

Jessica treasures moments like this, when they can all forget what happened. But it instantly makes her feel guilty for enjoying her children. So many parents in Uvalde lost their children last year.

“It breaks my heart that I have mine and they don’t,” Jessica says. “The guilt eats me up.

“I just feel so blessed to still have them with me.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/5ef1b2c10ca9b4ebf3a5b4ee36acd4d1/A_009518.jpg)

In the first weeks after the shooting, Jessica gave media interviews explaining that while her children weren’t physically harmed, the tragedy affected their entire family’s mental health. She opened a GoFundMe account to help with their medical and therapy costs.

Most people were supportive, she said, but some strangers sent ugly messages, telling Jessica that her children don’t deserve help because they shouldn’t be considered survivors.

One person wrote: “Why is Illiaña getting help if she’s not one of the survivors?”

Later in the evening, Jessica gets a call from Ameliaña’s best friend’s mother, who tells Jessica that her daughter has troubling screenshots of a private chat group. A teenager in the group told the other participants that he hated Ameliaña and threatened to hurt Ameliaña’s father.

This worries Jessica enough that she goes to the police station to file a report, worried the boy may follow through on his threats.

Before May 24, Jessica says, she would have dismissed the incident.

“Before, I’d be like, ‘Déjalo,’” — let it go — “‘they’re just kids talking shit,’” she says. “But now you can’t second-guess yourself. Now that we know what could happen, now that we know kids have access to guns.”

February 23

After dropping the kids off at school on Thursday, Jessica drives an hour and a half to San Antonio for a follow-up appointment with her cancer doctor. The MRI results show she has another nickel-sized tumor, but the other tumors have shrunk. The doctor says she can continue with oral chemotherapy but eventually she will have to go through radiation.

Jessica plans to push that off for as long as she can.

“My biggest priority right now is to keep Nana safe at school and deal with the bullying,” Jessica says. “I usually put what the kids need first before anything else.”

The cancer isn’t her only worry: Before her diagnosis in November, Jessica developed desmoid tumors in her left leg — they aren’t cancerous, but they cause her constant discomfort.

“I’m in a lot of pain,” she says, rubbing her thigh as she picks up the boys’ clothes from the living room floor after returning from San Antonio. “Usually, it’s at night that I deal with a lot of pain, but I think it’s because it’s been hectic lately.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/f9b96c270a61db51fda3721d306704c5/0221 Trevino Family EL TT 28.jpg)

Doctors have told her that surgery is an option, but there’s a risk the tumors will grow back. The pain gets so bad that Jessica says she’s thought about amputating her legs.

“My doctor said, ‘I’m game if you’re game.’ But we think about the kids a lot,” Jessica says, standing over a pile of laundry before she goes back into the kitchen to season chicken for dinner.

* * *

Having both parents in wheelchairs isn’t an option. David does what he can to help Jessica, but in his mind it’s not enough.

“I’ve always worked, that’s how I was built,” he said on a recent afternoon as he watered his lawn outside of their four-bedroom home on a quiet street shaded by large trees. “Sometimes I want to go to work but I can’t.”

As a boy, he earned money collecting lost golf balls at the local country club. As an adult, he worked in the oil fields, operated heavy machinery and then became a truck driver. In November 2019, he was driving an 18-wheeler on a rainy day and lost control. The rig rolled and threw him out of the cab. He survived but was paralyzed from the waist down.

Still, he helps around the house. He cooks, he plays basketball with the boys, he coaches Austin’s football team and he drives the kids to practice — he plays softball in a wheelchair league and connects with his children through sports. At his daughters’ softball games, he’s among the loudest parents.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/aa8fae0e35be3317471c5d41c6a081cc/0221 Trevino Family EL TT 18.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/a14d4781a95fd035f9e2d618cac62054/0222 Trevino Family Week 2 EL TT 03.jpg)

Jessica and David met at a dance in 2008, two years after she had moved to Uvalde from her hometown of Houston. They started dating and nearly two years later Jessica was pregnant with Ameliaña. They got married in July 2011.

Since the shooting, Jessica says she wants to move out of Uvalde. She wants her children to grow up somewhere far from reminders of the shooting.

“I want my kids to get better, but how can I do that if they’re in the same spot?” she says.

David says he doesn’t want to move — he was born here and loves Uvalde too much. He says he wants his children to grow up with the same positive experiences he had.

Despite what happened at Robb, David still feels like Uvalde is a safe town — as safe as anywhere else anyway. He can go to El Herradero de Jalisco, a town watering hole, for Mexican food and see the same people there every time.

“I don’t have to worry about who’s around me and my kids,” he says.

March 21

It’s a sunny afternoon in March, and Austin is in the backyard hitting softballs off a tee into a net. He says he stayed home from school this morning because he had a hard time falling asleep the night before and woke up with a fever. Jessica gave him the benefit of the doubt and let him stay home.

Nearly every day since the shooting, Jessica has to convince Austin or Illiaña to go to school, and they miss school at least once a week. Sometimes Jessica gets a call to pick them up before the school day is done because Illiaña has a panic attack or Austin’s anxiety gets too intense.

Austin admits that he wasn’t really sick this morning: “I had a bad thought last night that I was going to be in a mental hospital,” he says, picking up a softball and setting it on the tee. He spends the next half hour methodically hitting balls, working on his swing.

“One more for the fans,” he says, pretending he’s in a real game. He swings but barely chips the ball, which dribbles off the tee.

“The fans deserve better,” he says, grabbing the ball. He swings again, this time hitting the ball squarely. It soars in the air before hitting a tree in the backyard.

“Yeah!” Austin yells, dropping the bat and running inside the house.

Illiaña emerges to take her own batting practice. Jessica wanders out to the backyard to watch as her daughter gathers the neon-colored softballs, puts them in a bucket and places one on top of the tee. One by one, she hits the balls into the net.

A few hours earlier, Jessica had rushed to Sacred Heart with hydroxyzine, used to treat anxiety, after the school called to tell her Illiaña was biting her fingertips and hyperventilating. Jessica decided to bring her daughter home. After the shooting, a doctor diagnosed Illiaña with post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder and Graves’ disease, an autoimmune disorder.

Jessica watches as Illiaña practices, wondering why her daughter continues having panic attacks and whether they’re going to increase as May 24 approaches.

“I don’t know if it’s the anniversary coming,” Jessica says.

She’s noticed that on the 24th of any month, Illiaña and Austin get more anxious and Illiaña’s panic attacks are more frequent. And just a mention of Illiaña’s best friend can trigger a panic attack.

Before the shooting, Illiaña was targeted for constant bullying by her classmates. Her friend was always there to confront the bullies. Now she’s gone, and Illiaña is dealing with a new set of bullies at her new school.

“Nana gets teased a lot about her height and weight,” Jessica says later as she fries corn tortillas in oil on the stove while Ameliaña does homework at the kitchen table. “I have to keep reassuring her there’s nothing wrong with her, that it’s OK to be different.

“It hurts me to see her crying because she doesn’t feel like she’s good enough to be someone’s friend,” Jessica adds. “And it’s just me to reassure them.”

March 22

Most days are unpredictable in the Treviño house. Jessica and David try to maintain a routine for their children, but anxiety and panic attacks force them to improvise.

At about 11:30 a.m. on a Wednesday, Jessica packs sandwiches in a red lunch bag with Ameliaña’s name on it, then drops the bag off at school and returns home to help her husband get dressed and in his wheelchair.

Half an hour later, a staffer at Sacred Heart leaves Jessica a voicemail, asking if she wants to bring Illiaña’s medication or pick her up — she’s having another panic attack. Jessica rushes to the school.

“This is always the worst part,” Jessica says on the way to the school. “I don’t know what I’m walking into, like does she just not feel well, or is she having a panic attack?”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/bee84347b22f86a258c689cb0d406bf1/0321-25 Trevino Family Week 2 EL 05.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/3cf33f12ccaf9db1261171f53ceee1c7/0321-25 Trevino Family Week 2 EL 03.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/5368d6ec9210d99d7abace5e2b587d8c/0321-25 Trevino Family Week 2 EL 06.jpg)

Jessica goes into the school and emerges a few minutes later holding the 12-year-old’s hand. They get into the car and Illiaña says her stomach and lower back were hurting.

“Something was going through my head,” she tells Jessica.

“What did your counselor say you do when that happens?” Jessica says. “To think of something else and breathe.”

“But I couldn’t,” Illiaña says.

“What did you dream about last night?” Jessica asks Illiaña.

“About being at Robb and everyone was there and the kids screaming and yelling.”

When they arrive home, David is in front of the house, smoking a cigarette.

“Are you all right?” he asks Illiaña.

“My back was hurting,” she tells him.

Inside the house, Jessica gives Illiaña a pill, which she swallows with a drink of water.

* * *

An hour after Illiaña gets home, Jessica receives another message from Sacred Heart, asking her to bring a set of clean clothes for Austin, who had an accident at school. She grabs a pair of red shorts, a T-shirt and Huggies wet wipes.

“It’s one of those days, David,” she says.

“Tell me about it,” he says.

On the drive, Jessica says she’s going to take Austin home.

“As a parent, you’re never ready for stuff like this. We tackle it because we’re moms but deep down it tears you up inside,” she says.

She says she and David have tried to understand what their 9-year-old is going through. They have repeatedly asked him what’s wrong.

“When it first happened, Austin told me, ‘That guy got me all screwed up in the head,’” Jessica says, referring to the shooter.

“ ‘You can’t let him win,’ I told him,” Jessica says.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/915c08fcb6030c8990fdee727879f8e8/0322 Trevino Family 42.jpg)

She goes into the school again and comes back out with Austin. On the way home, they stop at a convenience store, where she buys him some chicken tenders and a bottle of Coke. When they arrive home, Austin showers and emerges in clean clothes.

He grabs his Coke and goes into the backyard, where he lines up the bottle cap on the edge of a handrail and opens the bottle with a quick smack of his hand. The Coke fizzes out and he immediately begins to drink it before it spills.

He says last night he heard loud bangs outside his home and the noise kept him up and made him anxious. In class, he kept thinking about what those sounds could be. He says he decided not to tell his teacher what was going through his mind that caused him to have an accident.

Chubs, Austin’s brown and white bulldog, starts reaching for Austin’s food. The boy wraps his arms around the dog.

“He protects me from dangerous people,” Austin says.

* * *

After Jessica picks up Ameliaña and David James from school, she tells the girls to get ready because it’s picture day for the softball team.

Illiaña sits in her bedroom and begins to cry. Jessica goes into her room, strokes her hair and asks her what’s wrong. She tells her mom she doesn’t want to take pictures.

Jessica asks her why.

“They’re going to make fun of me,” Illiaña says.

Austin goes inside the bedroom and asks his sister what’s wrong. Illiaña, irritated, yells: “Get out of my room, close the door.”

Jessica leaves Illiaña’s room and begins to curl Ameliaña’s hair as the teenager sits on a chair in a living room, watching a video on her cellphone.

“It just hurts to see her like that,” Jessica says, passing a curling iron through Ameliaña’s hair. “She is just having a shitty day all around.”

When Illiaña finally emerges from her room and sees her sister ready for pictures, she decides to go after all.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/cebb4b29a31427e11cfdce4f5fa6bb1c/0321-25 Trevino Family Week 2 36.jpg)

March 24

Like most Fridays, David is grilling dinner for the family. The house is full of people: Their neighbors are here along with two of David’s cousins, Oscar Treviño and Ida Velasquez, who brings her 8-year-old daughter to play with the Treviño children.

The smell of boiling beans fills the kitchen. Outside, smoke pours from the grill and Mexican corridos play on a Bluetooth speaker as Austin and David James play basketball in the street, teaching Velasquez’s daughter how to shoot.

Illiaña stays in her room and begins to cry. Jessica grabs a bottle of pills and rushes into her daughter’s bedroom along with Velasquez.

“You’re OK,” they tell her.

“No, I’m not,” Illiaña snaps back.

Jessica calls for Ameliaña, who tries to get her younger sister to start a breathing exercise.

“I can’t,” Illiaña says.

Velasquez tries to rub Illiaña’s back to console her, but Illiaña doesn’t want to be touched.

“Let go! Let go! Let go!” Illiaña screams. “Stop touching me.”

Jessica tries to convince Illiaña again to do a breathing exercise. Illiaña buries her face into a plush bear and muffles, “I’m sorry.”

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/4920c4aaf957615871cd1b9ffb3a8349/0321-25 Trevino Family Week 2 41.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/3a98d0a5d21a9f535bb9735e452c6d55/0321-25 Trevino Family Week 2 43.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/dab60cff5f9845ffa804ac9c89977789/0324 Trevino Family 67A.jpg)

Illiaña then starts to bite her fingertips. Ameliaña rushes out of the room to get Steve, her favorite kitten from the litter that the family cat gave birth to recently. Ameliaña passes the kitten to Illiaña and after about 15 minutes, Illiaña calms down.

Everyone leaves the room. Illiaña stays in bed, caressing Steve.

In the kitchen, Velasquez wants to cry, too. It hurts her to see her niece struggling. Jessica tells her to hold it together. If Illiaña hears or sees her crying, she may break down again.

“You have to be mentally strong to go through this, because look what time it is,” Jessica tells Velasquez. “It’s not like you can take the kids anywhere right now for help.”

After dinner, Illiaña finally emerges from the house, walks to her aunt and hugs her without saying a word.

“You OK, mija?” Velasquez asks her. Illiaña nods her head.

It’s past midnight before the house is finally quiet again. Jessica walks to the back porch and lights up a Marlboro, staring off into the night. She leans against the porch railing, arms crossed.

“I come out here to think: ‘What can I do better the next day?’” she says, then stubs out the cigarette and flicks the butt into the yard.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/713552d4a098a53d0f27da8f5fa6ee4a/0321-25 Trevino Family Week 2 52.jpg)

March 25

The next day is Saturday, and like most weekends, the Treviños try to spend time away from the house as a family.

They pile into the pickup and drive to Del Rio, pulling up to a house where a group of men dressed in boots, denim jeans and black leather vests with the Bad Company motorcycle club logo are waiting with their Harley-Davidson motorcycles.

The bikers greet the Treviño children warmly.

The motorcycle group is made up of military veterans who routinely participate in public events to help raise awareness about mental health issues. Last summer, shortly after the shooting, the club came to Uvalde to take part in a community event for children affected by the shooting and met the Treviño children.

As part of the event, Austin also got to smash a pie in club member Albert Treviño’s face. Since then, Albert — who served four years in the Army, including a tour in Afghanistan, and was diagnosed with PTSD in 2016 — has stayed in touch with Austin and his family. Albert, 33, said he and Austin got along right away because of the boy’s charismatic personality.

He said he appreciates the Treviños doing everything they can to provide a support system for their children, even with their limited resources. He said his brother, who did two tours in Afghanistan with the Army, took his own life after struggling with PTSD, so Albert wants to give the Treviño children another adult to turn to for help.

“Growing up in a Latino family, mental health is kind of like a joke,” he said. “They say stuff like, ‘No, pobrecito, esta menso’” — No, poor him, he’s just dumb.

The bikers help Illiaña, David James and Austin put on helmets. The children sit behind the men, who rev the Harleys’ engines before they take off on rides around the city.

Alexander “Tripp” Arneson, a club member, said that veterans diagnosed with PTSD use motorcycle riding as a form of therapy.

“Riding the bike, you feel the cold wind hit your arms and just feel the speed of the bike,” he says. The club, he adds, wants to help the children create happy memories and have something positive to think about when they’re feeling anxious.

“They shouldn’t go through with what they experienced,” he says. “So whenever they’re feeling bad, this helps them remind them that there are people who care for them.”

When the rides are done, the family decides to go to Blue Hole Park, a popular local swimming spot.

The children excitedly run to a bridge over a broad stretch of San Felipe Creek and jump into the water.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/9d67aa8dbc8e8491d981fa83d0bbd99c/0325 Trevino Family 054.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/a8cc488e24dd2003bdfe824f7e319e9e/0325 Trevino Family 058.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/a672d901b64d037c0907f9b1217b4f54/0325 Trevino Family 069-2.jpg)

David waits in the truck, out of the sun, while Jessica sits in a lawn chair nearby, wearing a hat and sunglasses, and watches her kids frolicking in the water. She wonders out loud: “Do you think the world still thinks of these kids?”

“Not really,” Illiaña chimes in as she emerges from the water, dripping wet in her basketball shorts.

“So you think they’re just like, ‘Whatever’ now?” Jessica asks.

“Yeah, there are other things that are happening in the world,” Illiaña responds before diving into the creek again. A teenage boy asks Ameliaña for her number. Austin chases him off with a Nerf water gun. “Get away from my sister,” he says.

Jessica smiles.

“At least they get to be kids here and be worry-free,” she says. For a little while, everyone is happy, and the day that a teenager walked into a school with a rifle and changed their lives feels far away. That’s what Jessica and David want for their children — to be able to forget and just be normal kids again.

“I don’t want them remembered as Robb kids,” Jessica says. “I want them remembered as good kids.”

May 20

It’s four days before the one-year mark of the Robb Elementary shooting. The Treviños have decided they don’t want to be in Uvalde for it. So they’ve rented an Airbnb in Del Rio for a week.

The children are excited to go. “It’s a lot of fun over there,” David James says.

“I think the kids need a break from everything going on here,” Jessica says. “It’s just not good for them, it’s not good for their mental health.

“Maybe next year will be different.”

This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune, a member-supported, nonpartisan newsroom informing and engaging Texans on state politics and policy. Learn more at texastribune.org.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/21745f313e3bc19b08eba213a6f1e0e9/0321 Trevino Family Week 2 EL TT 02.JPG)