Amid COVID, Closures & Zoom, a Teacher Fights to Preserve School Relationships

Through team teaching, straight talk and showing up in unexpected ways, Baltimore’s Kyair Butts kept students together and learning during tough times

By Greg Toppo | May 31, 2022This is one article in a series produced in partnership with the Aspen Institute’s Weave: The Social Fabric Project, spotlighting educators, mentors and local leaders who see community as the key to student success, especially during the turbulence of the pandemic. See all our profiles.

On March 13, 2020, Kyair Butts and his sixth-graders were deep into a particularly engaging forensic anthropology lesson, trying to answer this question: Why did Virginia’s Jamestown settlement collapse?

At the time, Butts — universally known as “Mr. K” to his students and colleagues and simply “K” to his friends — was a language arts teacher at Waverly Elementary/Middle School in Northeast Baltimore. When COVID-19 hit, he and his students were mere weeks from the end of the school year.

That evening, Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan ordered schools statewide to close immediately. The city system, along with Maryland’s other 23 school districts, would shut down for a full two weeks, with a plan to reopen in early April.

Butts was worried. “If I waited two weeks, I’m just convinced that I would have lost some students — and lost some families,” he said. “And we just don’t have time for that.”

So he contacted all of his families and told them he’d be on Zoom first thing Monday morning, no matter what — greeting students, hearing about their weekends, commiserating, sharing fears, and teaching a lesson.

While virtually every other school in the city took a break, his students logged on, attended abbreviated classes and quickly learned about Zoom waiting and breakout rooms.

That sent a message.

“Families just really appreciated that,” he said. “So, in turn, they showed up. That’s all I can ask.” To be exact, 25 of his 60 students showed up. As the week progressed, that number grew, to 35, then 40, then 45.

Two years later he’s teaching at his third Baltimore school, Henderson-Hopkins, a pre-K-8 school that partners with Johns Hopkins University, located just blocks away. With the pandemic entering its third year, this Iowa transplant has become not just a go-to expert for advice about how to reach students remotely. He has established himself as a constant, supportive presence in his students’ lives, both inside and outside school, and an unlikely role model for young people growing up in a very different time and place than he did.

Honored in 2019 as Baltimore’s Teacher of the Year — district CEO Sonja Sontelises cited his “passionate commitment to student achievement and equity” — Mr. K. sees teaching as more than just a job.

One weekend a month, he brings students to get free books at the Maryland Book Bank. Then he takes them out to brunch and, on occasion, to attractions like Baltimore’s National Aquarium. The outings further cement his bond with families, said Henderson-Hopkins Assistant Principal J.D. Merrill. “That relationship piece is something that you can’t really quantify, but it translates into academic gains because the kids will work for him. They know he’s there for them, that he loves them.”

The ‘super magical’ promise of Zoom

When school shutdowns forced him to begin teaching almost entirely from his bedroom, he was sharing a Baltimore townhouse with two other teachers. One was a special education teacher at a local high school who taught from the adjoining bedroom, and another was a tutor for the startup Amplify, who conducted 20-minute lessons from the dining room.

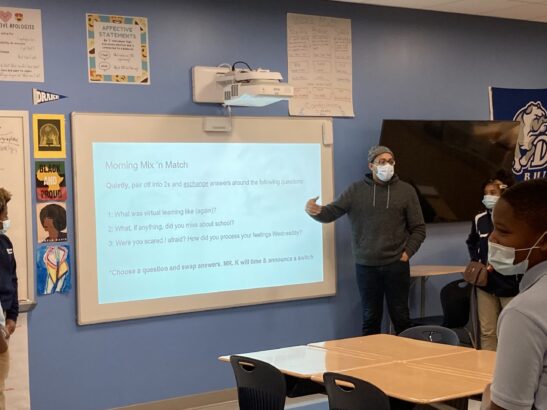

Butts learned that in other Baltimore schools, teachers at the same grade level were logging onto a single Zoom link and taking turns working as lead teachers. He and his colleagues tried it, adding a dedicated special education teacher to the mix and teaching one lesson apiece each day, as opposed to the typical model, in which each teacher delivers the same lesson to several classes throughout the day.

While one teacher taught, the others provided support, answering students’ questions via Zoom chat, monitoring student work, and moving students into breakout rooms for individualized or small-group instruction. That kept students focused on the lessons and, in the bargain, standardized teachers’ expectations across the team, helping students figure out how to succeed day by day.

“My colleagues were also able to see me teach for an hour every day — and I was able to see my colleagues teach for an hour every day. We’d give each other really good feedback and great debrief sessions,” he said. “We kind of tweaked our practice so that there was a unity among what students were hearing, by way of expectations — it was actually super, super magical.”

It also simplified the school day for families, who only needed to log on to one Zoom address each day instead of four or more. In all, students received about three-and-a-half to four hours of instruction each day.

While attendance was rarely perfect, he said, 55 to 58 of 70 students would show up most days — a respectable 79 to 83 percent attendance rate, during a school year in which Maryland school systems collectively lost an estimated 27,000 students, according to one analysis.

Two years later, Butts has retained his sense of urgency. “Zoom and remote learning has so much potential,” he said. “The problem, though, is that potential is still at rest until something gives a push to become kinetic and something kind of magical and brilliant.”

Love & straight talk

The magic that Butts offers is a dose of honesty about life and the world that is often missing in the daily press to teach content to students. The honesty lets him and his students talk about things that matter and be vulnerable with each other.

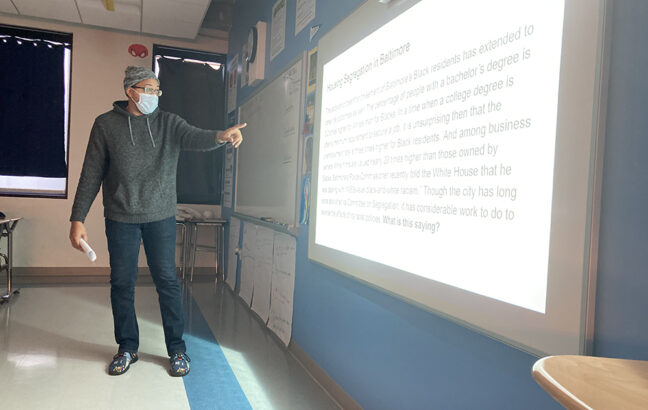

Each year, he shares with his students a 2015 Washington Post article, based on the ground-breaking research of Harvard economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, detailing the risks of growing up poor in Baltimore. The researchers found, for instance, that every year a poor boy spends growing up in Baltimore means a 1.5 percent drop in his earnings as an adult; if a young man spends his entire childhood in the city, by 26 he’d earn about 28 percent less than if he’d grown up nearly anywhere else.

Butts translates data about Black Baltimore students’ achievement into a picture of what awaits them as young adults. If they’re not reading on grade level, for instance, their risks of not graduating high school rise, as do their chances of being incarcerated. Assistant Principal Merrill said, “He just makes these connections between what’s happening, but then he doesn’t make the kids feel bad about it. He has a plan: ‘This is what we’re going to do to get you caught up.’”

Because of recent interruptions in their schooling, that straight talk has never been more important, Butts said. “I’ve been very clear with students this year: ‘I’m going to be very transparent with you. I want to be open with you, I want to be vulnerable with you. But because I love you, I’m also going to tell you things that you need to hear versus things that you want to hear.’”

Butts’ life story offers up a different kind of narrative of growing up Black.

By his own admission, Butts led a “pretty middle-class” life: a child of divorce raised on the south side of Des Moines, he was liked by teachers, with a loyal group of mostly white friends. He liked school and thrived, especially in high school, where debate and mock trials fired his imagination.

Being Black in “majority white spaces” gave him an awareness of a kind of implicit spotlight that shone on him. He fit in at school and knew that his friends and their parents respected him.

Actually, his classmates went a step further, electing him “Man of the Year” in his junior year. That shocked him. Butts knew he was well-liked, but never thought of himself as popular. “I could kind of blend in with various different friend groups or different kids, but I just didn’t think I was in the ‘In’ or the ‘It’ crowd.” To win Man of the Year proved to him “that I belonged.”

Decades later, that quiet confidence shines through — as does a decidedly Midwestern sensibility and set of tastes that he can trace to his youth: He likes Marvel superhero movies, progressive rock, and Ultimate Frisbee. In that way, colleague Christina Bradford said, his students get to see “a different representation of Blackness.”

Butts, who sports thick black eyeglasses, laughed when asked during a midmorning recess period about his tastes in movies, music, and sports. “A little Ben Folds never hurt anybody,” he joked. “So we’re going to listen to it. I just choose me, and I hope that some kids are like, ‘You know what? I think I can choose me too.’”

‘He believes that Black students deserve the best’

Butts actually showed up at Henderson-Hopkins nearly three years ago to lead a teacher training, recalled Merrill. But as he and Principal Peter Kannam looked on, they were instantly impressed with his ability to both deliver the material and connect with teachers. Merrill pulled out his phone and texted his boss: Are you thinking what I’m thinking?

Merrill ran back to his office, typed up an offer letter, dug in a closet for a Henderson-Hopkins backpack, hat, and folder, and ran back to the training room. Kannam signed the letter and they handed the odd parcel to Butts, even though they had no open positions.

Eventually Bradford, the math teacher, accepted a job there — with the requirement that she and Butts could teach as partners. They both began teaching there last fall.

“You can tell that he treats each student as if they were his own kids,” she said. “And he is very clear about his expectations for them and truly believes and acts in a way that he believes that Black students deserve the best and are the best, which is really refreshing to experience and work alongside.”

Principal Kannam said walking the line between friend and teacher is harder than it looks. “Everyone says, ‘Relationship build,’ but it’s not to be students’ friends,” he said. “You’ve got to get them to work for you.”

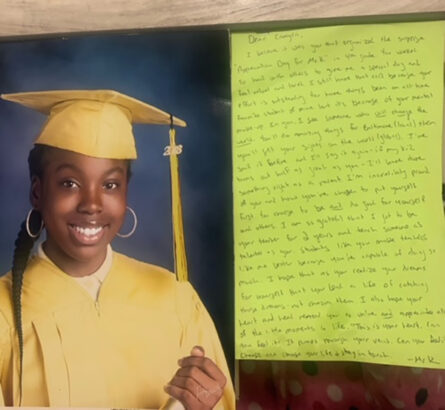

Camyra Williams, 18, vividly remembers Butts’ class at Calverton Elementary-Middle School, where he taught her for fourth and fifth grades. Even now, she said, they talk regularly about school, and about life.

Williams remembers that he helped her come out of her shell, especially during preparations for debates, which taught her to both embrace the ideas she cared about and think about them logically.

“I put up a pretty good fight now, I’m not going to lie,” she said with a laugh. “Anything that I feel strongly in, nobody can beat me.”

At the end of her fifth-grade year, she was so grateful that she arranged a party in his honor, which she dubbed “Appreciation Day for Mr. K.”

She still relies on an exhortation he used to share with students: “Mind over matter.”

“It didn’t click with me at the time,” she said. But as she got older, it began making more sense: Everybody has hardships and bad days, she recalled him saying. You’ve got to accept that and keep going in life, no matter the obstacles. “It’s being able to control it, not letting it control you.”

A senior who’s due to graduate next month from Baltimore’s Western High School, Williams still keeps a hand-written letter Butts wrote to her (and every other student) for fifth-grade graduation. It sits in a mirror frame, next to her graduation photo. In the letter, he tells her, “In you, I see someone who will change the world.”

“He didn’t have to do what he did, kind of like the typical teacher, the typical person,” Williams said. “But he wasn’t. And I will forever cherish him for that.”

‘This generation is in no way lost’

On a recent morning, a cool jazz ballad played softly on the classroom stereo as Butts led 24 sixth-graders through a reading lesson. He urged them to sound out large, unfamiliar words such as “humanitarian” syllable by syllable, in their heads, much as they once sounded out simpler words like “cat” when they were younger.

He clapped out “hu-man-i-tar-i-an” saying, “I know it sounds silly, it sounds a little elementary. But your brain is going to thank you.”

With a passage from a reading about the Black photographer Gordon Parks on a projector screen, he led students through an “echo read” of the passage, reciting short phrases that they repeated, en masse, like a congregation following the lead of a minister.

The technique is a standard one, but he brought it into the classroom, he later said, because he’s thinking more and more, post-pandemic, about the importance of reading fluency. “I haven’t spent this much time ever truly focusing on fluency,” he said. “There’s a precision to this.”

Being able to read is one thing, he said, but being able to demonstrate it is another. “Working on fluency has to stay going forward,” he said.

As schools look past the pandemic in 2022 and beyond, Butts said he’s hoping the public will rethink its idea of how students like his have fared. The dominant narrative is that remote learning was a disaster and that millions suffered possibly irretrievable “learning loss.” One July 2021 study from the consulting firm McKinsey & Company found that students, on average, were four months behind in reading and five months behind in math by the end of the last school year.

In Baltimore, the most recent statewide test results show that just 19 percent of city middle-schoolers read proficiently, compared to 37 percent in nearby Baltimore County and 53 percent in suburban Howard County.

Butts said he saw a different reality with his students.

“They really attacked school,” he said. “Yeah, there were some students for sure who are in sixth grade that need some decoding practice, but I’ve also seen that before there was ever a pandemic. And the students that I had the virtual year, they were engaged — they asked questions. They found ways to just get it done.”

He also roundly dismisses any talk that his students risk becoming a “lost generation,” as several critics have warned.

“If anything, I would like to think that it’s a ‘generation of opportunity,’” he said. “The coolest part about being a teacher, I like to think, is that every day you get to do something that allows others to present their best selves to you. And if that to me is a measure of success, aside from academics, this generation is in no way lost.”

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to both the Weave Project and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter