For Maverick Polly Williams, the Mother of School Choice, The Point Was Always to Empower Parents and Improve Education for Black Children

When Annette “Polly” Williams died in 2014, she had spent 30 years as a Wisconsin state representative — the longest-serving woman in the Wisconsin Legislature. But it was her efforts in the late ’80s and early ’90s to create the nation’s longest-running private school voucher program that marked her career. The Milwaukee Parental Choice Program, or MPCP, offered parents with limited means public funds to send their child to a nonsectarian private school.

Williams and her staff drafted legislation leading to MPCP. And she brought together an unlikely bipartisan coalition of moderate Democrats and Republicans, as well as a grassroots coalition of parents and community leaders to get the bill passed. Tommy Thompson, the Republican governor at the time, had tried for a few years unsuccessfully to move similar school choice legislation. But it wasn’t until Williams, a Democrat, black activist and community organizer, took the helm that it succeeded.

For her efforts and influence, Williams has been called the “mother of school choice.” At her funeral, however, those closest to Williams were careful to qualify that legacy. “I was a Polly Williams choice person,” said a longtime colleague and friend. “She had a permanent interest in helping black people, and helping poor black children.”

Although many proponents celebrated the controversial parental choice program because of its historic introduction of competition into the public education space, this was not Williams’s ambition. To suggest that free-market theorist and economist Milton Friedman was her muse would cause her to balk. In fact, she admonished me for even using the v-word.

“Don’t call it a voucher plan,” she told me in 2012 during one of many interviews. “That’s not what I call it. It’s parental choice. My focus is always empowering the parents.”

Williams’s specific ambition was to empower low-income and working-class black families in Milwaukee to have more control over a variety of aspects of their lives, one of the most influential being education. MPCP was just one of many efforts she championed in this cause. In her 10 years in the state Assembly leading up to MPCP being enacted in 1990, she worked to give the black community more control over Milwaukee Public Schools in hopes of reversing its long record of underserving black kids.

She pushed for more black teachers and black paraprofessionals, believing that black educators would have a greater impact on black students. (A theory that research now supports.) She introduced legislation to redraw school board election district lines to increase black representation and give Hispanic voters a chance to elect a board member.

She also fought to keep the city’s court-ordered school desegregation plan from overburdening black families and decimating majority-black schools. Key tenets of the plan included closing inner-city schools, converting neighborhood schools into magnet schools and busing students to achieve a racial balance. In each instance, black families were disproportionately impacted. Williams joined other community activists, including Howard Fuller, who would later become the Milwaukee Public Schools superintendent and subsequently an influential parental choice advocate, to mitigate that impact.

She supported Fuller’s bid to keep North Division High School (Fuller’s and Williams’s alma mater) from becoming a specialty school and displacing hundreds of black students. She introduced legislation to create a separate, majority-black school district, one where black educators and community leaders would have the resources and control to provide and decide what was best for black students and where more black students would be able to stay in neighborhood schools.

Ending forced busing, however, was the issue on which she was, perhaps, most consistent and persistent. In 1987, she introduced an amendment requiring parents and guardians to give written permission before their child could be bused to another school. Two years later, addressing her colleagues on the Assembly floor in 1989, she called on them to end “intra-district transfers” in particular. At the time, she said, of the 33,000 Milwaukee students who were being bused inside the city, 20,000 were black students being bused from one black school to another.

“They are not being bused for desegregation purposes. They are not being bused for specialty schools. They are just being bused for the sake of being bused,” she said. “Assume your responsibilities as state legislators who are responsible for the education of all children in the State of Wisconsin and take his burden off the backs of black students.” (*Transcript published in The Milwaukee Courier, July 1989.)

A mother on a mission

The busing issue is what initially drew Williams to grassroots activism. In the 1970s, she joined Blacks for Two-Way Integration, a group of mostly parents calling for black and white families to equally shoulder the burden of integrating schools. The group was organized by Larry Harwell, a known community organizer who would later serve as Williams’s chief aide and thought partner for much of her efforts to give the black community more control.

The group’s motto was “two-way or no way.” They were angry that their children had to wake up early and endure long bus rides, while white students remained in their neighborhood schools. Black parents were also frustrated because they couldn’t be as engaged as they wanted to be, finding it difficult to make it across town for parent-teacher meetings and to intervene on their child’s behalf when they needed to.

Initially, Williams said, “I was one of those parents who bought into integrating. … The perception was wherever white kids are, white parents are going to make sure their kids got the best.” So, she fought to get her oldest daughter’s assignment switched from a majority-black high school to a more integrated one. Officials originally denied the request, claiming that the school’s racial quota had already been met. But Williams persisted. Her oldest daughter remembers her mother telling school administrators that she would “go to school at Riverside or not at all.” And when officials warned Williams that truancy would land her in jail, she gave them her address, telling them where to find her. Her daughter also remembers her mother going up to the school and having meeting after meeting after meeting. “They got sick of Ma,” she said. “She bullied her way through.”

All four of Williams’s children would go to Riverside. But Williams marks that initial rejection as a turning point for her. For one, it made it clear to her that the city’s desegregation efforts were more about racial quotas than making sure black children in the city had access to a quality education. “Our children were being taken out of our community to integrate another community under the guise that it was a better education for them,” said Williams. “We didn’t see that it was necessary that black students’ education had to be tied to integration with white kids.”

To accept the premise that black kids had to go to school with white kids to get a good education meant that all-black educational settings were inherently inferior. This was far from what Williams, Harwell, Fuller and other community activists she worked closely with believed. Before she pushed to get her kids into Riverside, she sent them all to Urban Day, an independent majority-black community school serving grades K-8. Williams said she read in the paper about Urban Day, a former Catholic school that was reopening as a private school and where low-income families could pay on a sliding scale. To offset tuition, Williams did administrative work — typing, answering phones, etc. Williams would maintain close ties with the school, even after her kids graduated, serving on its advisory board. Later, Urban Day would be one of the first schools to participate in the Milwaukee voucher program.

The Riverside rejection also showed Williams firsthand how it felt, as a parent, to know what was best for your child’s education and not be able to access it because of something outside of your control — setting the stage for the historic parental choice legislation to follow. Looking back at that experience, she said, “I would imagine that had something to do with my fight to have a quality education no matter where the child lived. That a parent ought to be able to get the best, whatever they decide for their children, whatever it is, whether it is all-white, predominantly black, Hispanic … good quality education ought to be there.”

The people’s politician

Williams got her political inklings from her cousin Monroe Swan, who in 1972 became Wisconsin’s first black state senator. She worked on his campaign and then a few others. And in 1976, at 39 years old, she ran for state representative against a Democratic incumbent who also was black. Recalling her initial campaign, she said: “Black folks saw me as a problem. ‘You’re running against this black man. You’re trying to put him out of work.’” But Williams said he was not a “good representative.” So, even though she helped get him elected in 1972, she “decided to take him on.” She was unsuccessful in 1976 and again in 1978. But in 1980, on the charm try, she won.

When Williams showed up in Madison at the State Capitol, she had only one loyalty — to the people who elected her. She didn’t get support or money from the Democratic Party, since she was trying to unseat an incumbent. The money she raised came from family and friends, she said. “As a politician, either you have money or people … I had people,” she said. Each time she ran and persisted, she made a name for herself, earning the respect of the community. “I was able to turn them around and see me as a viable person who could do a better job,” she said.

From the beginning, Williams showcased her independence in the Legislature. “I came there with an agenda that I got from the community. Not the agenda of the State Capitol, where the leadership dictated what you are going to do and what you are going to vote for.” She remembered, in her freshman year, refusing to follow party lines and vote against the Republican governor’s budget. The budget had money to support community-based organizations in her district, so she gave her first of many impassioned speeches on the floor on behalf of what was best for her constituents. She was so emotional, she said, she had to leave the room crying. But when she returned, she learned that her pleas had worked and she had just secured $3 million for her district, she said.

Williams recounted other instances when she “fought her party” and “refused to toe the line,” from policies regarding HMOs to serving as minister of education for Milwaukee alderman and former Black Panther party member Michael McGee’s black militia. “I was a shock to them,” she said of her legislative colleagues. “I was a single [divorced] mom, African-American and poor. I needed the job. I made more money than I had ever made in my life. Prior to coming to the Legislature, my income was $8,000 a year with five of us. And when I went into the Legislature, my income jumped to $19,000. I had never seen that much money in my life.”

But there were consequences to her independence. The Democratic Party, she said, funded candidates to run against her in her first and second terms in hopes of ousting her. She credits her strong base in the community for keeping her in office. “If they didn’t put you in, they can’t take you out,” she said. So, almost 10 years into her 30-year tenure, when the opportunity came up to work with another Republican governor to push parental school choice, a controversial issue that would further distance her from her Democratic peers but would benefit her constituents, she didn’t think of her party, but of her people.

Open invitation to the White House

In his memoir Power to the People, former Wisconsin governor Tommy G. Thompson writes that the idea for the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program originated during a meeting in his office at which Williams and Fuller were in attendance. Fuller, in his memoir, No Struggle No Progress, maintains that the idea emerged out of talks in the black community after the bid to create an all-black school district failed. And editor of the Milwaukee Community Journal, Mikel Holt, in a comprehensive firsthand account, Not Yet “Free At Last,” names an origin long before — as part of local black activists’ efforts in the 1970s to gain control over their educational destiny.

While there is discrepancy in the idea’s origin, there is no disagreement about Williams’s role in bringing it to life. Fuller, for example, writes that she deserves the “lion’s share of credit” for getting the bill through the Legislature and recently expressed that he’s “extremely disappointed that Polly doesn’t get the credit she deserves for so much of what’s happening today.”

Thompson corroborates a familiar story of Williams bringing busloads of parents, students and community activists to pack the Assembly gallery — a palpable presence for lawmakers as they voted on those same students’ educational fate. Holt gives great detail about Williams’s role in influencing her colleagues, as well as “sounding the trumpet” and “rallying the troops” among parents and community leaders. In all, she built strong public support among black parents, private school and community leaders and local black press. Together they organized a massive grassroots campaign (word of mouth, phone trees and flyers) to influence lawmakers.

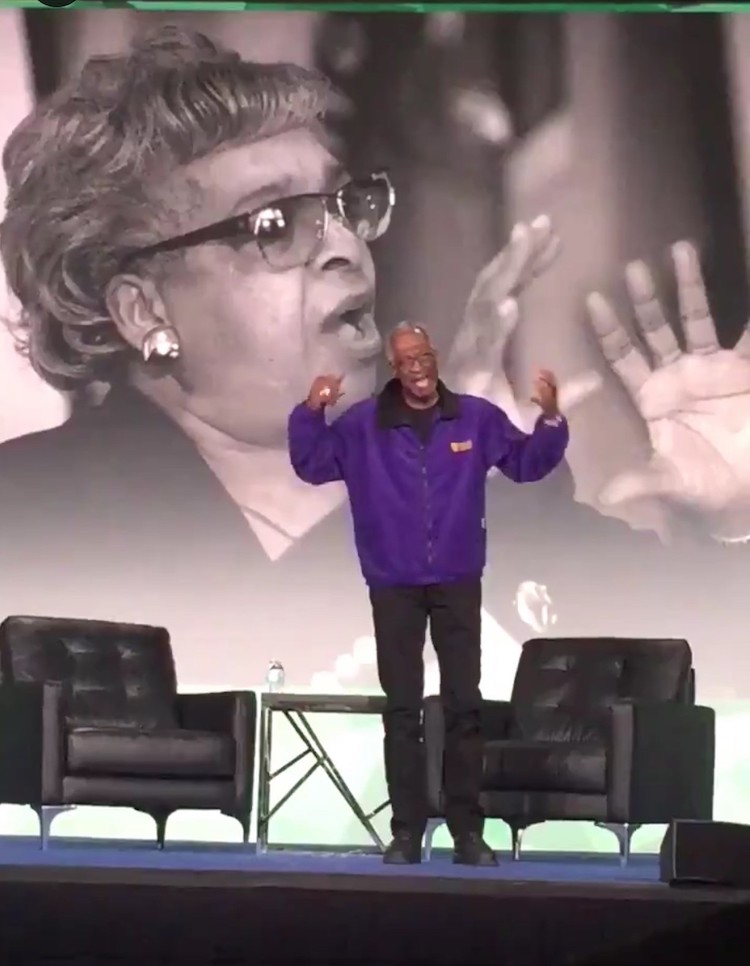

And yet, when Fuller asked the audience this past July at the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools’ annual conference in Las Vegas — a group that arguably owes its start to the Milwaukee parental choice program — if anyone had heard of Williams … few signaled yes. Williams’s story from being MPCP’s lead architect and proponent to near obscurity among today’s parental choice advocates is a complicated one, and one that has yet to be told — at least from her perspective.

In the years immediately following the program’s start, she traveled around the country and overseas as the voice of choice. “I spoke at the most prestigious places,” she said. Harvard, Stanford and the Brookings Institution are some examples. At Stanford, she said, she was on campus speaking the same weekend as Mikhail Gorbachev. “I was the Friday night banquet speaker, and he was the Saturday afternoon speaker.”

She was especially popular with conservative audiences and Republican lawmakers, who had been trying unsuccessfully to legislate private school choice for years. Ronald Reagan tried several times to introduce educational vouchers during his presidency. And George H.W. Bush continued the push early in his term. During the first Bush presidency, Williams said, she had an “open door policy” at the White House since she was invited so much. “I didn’t have to go in the way through all the security. The guy just told me to come to the back gate and they would just open it and let me in.” President Bush called her a “courageous hero” during a Rose Garden ceremony. And Newt Gingrich, she said, who was House minority whip at the time, told a room full of journalists from major outlets that they should all go out and write stories about her.

Many accused Williams of being naive and letting conservatives use her. But she said she was well aware of what she brought to their cause. “An elected official, an African American, a former welfare recipient, who was articulate, who could speak — they never thought they would get that. So I helped legitimize them.” She said she also knew that her conservative allies, mostly white and wealthy, had a long-range plan to create programs to benefit the rich: universal vouchers with no income limits. In the meantime, they needed low-income families like those she represented to open the door. So, just as she had, in her first term in office, taken advantage of a shared interest with those she generally disagreed with to benefit her community, she did the same.

But by the mid-1990s, that shared interest was not enough for Williams to set aside her core belief in black empowerment and community control. As the program expanded, the school choice coalition grew to include philanthropic foundations, religious groups and the business community. They helped bolster the program by funding organizing efforts and the many legal battles the program faced. But they were not typically controlled or led by African Americans. Thus, as they stepped up their efforts, Williams sensed she was no longer in control, and by extension she believed neither were the low-income and working-class black parents she had helped to organize.

“We just wanted the resources to allow [black parents] to be in control. I just didn’t see that,” she said. “Everywhere I went it was always white people. People whose background and their history was not serving or helping low-income families.”

Williams disagreed with the coalition on other matters. When the Legislature passed an amendment to make religious schools eligible, it increased the number of choice schools from 12 to 100 and students from 800 to almost 3,000 in a matter of months. (It also set in motion a constitutional battle that would hamstring the program for many years.) At the same time, by the mid-1990s, reports of choice schools closing due to cash flow problems, parents complaining of poor conditions and mistreatment, and other issues illuminated flaws in the program’s structure and the lack of regulation (not unlike the concerns put forth by many of today’s critics of similar programs).

Theoretically, the school closings could be considered signs of success, i.e., market forces at work. But Williams, who spent her days fielding complaints from choice parents in her district desperately scrambling to find new options when their voucher school closed mid-semester, couldn’t dismiss it as an ideological issue. “I’m not going to be an ostrich with my head in the sand pretending we don’t have a problem,” Williams told a local reporter.

Instead, she introduced amendments to limit religious school participation, strengthen oversight and make the choice schools more accountable. She also moved to limit the seats allowed for religious schools, so the existing pioneering choice schools — the few independent community schools like Urban Day — would not lose their opportunity to expand and be replicated. It was not unlike when she tried to limit forced busing the decade before. In theory, integrated classrooms promised to lead to a better education for black kids. But in the present, black families were being treated unfairly. In either case, she focused on fixing the problem at hand. Nonetheless, calling for more government-imposed rules to regulate a market-based approach (and trying to slow religious school expansion) further put her at odds with her allies. As Williams began to speak publicly about her frustrations, she solidified her split from the Milwaukee coalition, ultimately distancing herself from a national school choice movement that she helped to spark.

Other community leaders, such as Fuller, stepped in to represent the interests of poor black families in the national school choice movement. In MPCP’s early years when Fuller was superintendent of Milwaukee Public Schools, he was restricted from advocating for the program. But once he resigned, he resumed his early activism, fighting to ensure that low-income and working-class families had access to quality education. More recently, however, Fuller has shared some of Williams’s frustrations. He includes details of his own split with longtime Milwaukee choice coalition members in his memoir. He also writes about the battle to keep Republican lawmakers from ending MPCP’s income caps altogether, meaning anyone would be eligible, including wealthy families who already have the resources to choose a better education — a fear Williams expressed early on.

Zakiya Courtney, a local community activist and Urban Day parent, would too emerge as an important leader in Milwaukee and in the national movement. She said that a lot of what Williams predicted came true, especially regarding the fate of the black independent community schools like Urban Day that pioneered the program. MPCP’s expansion to include Catholic and Lutheran schools left little room for them, she said. Today, both Urban Day and Harambee Community School, which shared a similar history and track record of successfully educating black children, are closed.

A Polly Williams choice person

Soon after her confirmation, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos evoked Williams’s legacy in a major speech on the Trump administration’s plans to expand school choice and then in testimony on Capitol Hill. Most recently, she referenced Williams during her back-to-school tour in September. DeVos, in an appeal to bipartisanship, championed Williams as “a Democrat city councilwoman [sic] … [who] bucked the system on behalf of the kids she loved.”

DeVos was (mostly) right about Williams’s early role in the parental school choice movement. But she left out the second half of the story, when, after hard-won experience, Williams also bucked her allies, many of them with privileged backgrounds like DeVos’s. Williams was not alive to hear DeVos’s reference or to witness the recent federal push to expand school choice initiatives. But a close look at her more than three decades of public service and advocacy for low-income and working-class families offers insight into how she might have reacted as well as into exactly what her longtime colleague and friend meant when she said at Williams’s funeral that she was a “Polly Williams choice person.”

It’s highly likely, for instance, that Williams would have been upset with reports of students taking hour-long bus rides to voucher schools, politicians profiting from tax-credit vouchers and policies that subsidize private education for the wealthy. She would have rejected programs with no accountability to serve kids with special needs and programs having no problem turning away students with disciplinary problems and been disappointed by the litany of data showing little gains for low-income students and students of color.

But she would have celebrated the stories of black and brown students succeeding in various educational settings. And she would have been pleased to hear of schools — public, private or charter — where both black students and black teachers say they feel welcomed, supported, motivated and culturally affirmed. And there’s no question she would have answered in the affirmative if she were asked the question today’s advocates are pondering: if “School Choice Is the Black Choice.”

Perhaps, most certain, she would have never questioned the role of low-income and working-class families in making decisions about their children’s education. That’s a premise she maintained. “When they ask me, knowing what I know now, would I still do it? I say yes. Even though I may not agree with a parent’s decision, they still have the right to make it,” she said.

Robin V. Harris is a former New America Fellow, writing a book about the life of her cousin Polly Williams. She is also managing editor at The Education Trust. Follow her on Twitter @RobinVHarris. Quotes from Williams and her family are all from personal interviews conducted in 2012-14, unless otherwise noted.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)