Texas, 78207: America’s Most Radical School Integration Experiment

By Beth Hawkins | October 17, 2018

In the nation’s most economically segregated city, an innovative new approach to school integration designed to address poverty, trauma, and parental choice is working

San Antonio, Texas 78207

J.T. Brackenridge Elementary sits on the eastern edge of zip code 78207, which is the way people refer to the Mexican-American community that surrounds the school. Located just west of downtown San Antonio, the neighborhood is as rich with art and history and culture as the rest of the city. Yet it’s a world apart.

To travel to or from the school is to take a compressed trip through time. Head east, and every few hundred feet Guadalupe Street presents a different line of demarcation — each a visual reminder of who lived here and what life was like during those respective eras of human habitation.

There’s Alazan Creek, one of the spring-fed waterways that drew nomadic tribes and Spanish conquistadors, now a concrete culvert lined, not with public art, like the city’s iconic Riverwalk, but with untamed scrub. After Guadalupe crosses the river, the road widens and rises, going over busy train tracks that conveyed the raw materials that were used to build the modern metropolis, and then the scrapyards to which spent rebar and steel are returned, to be reforged as the city’s next iteration.

The final boundary is an elevated interstate, a current-day conduit in the sky that bisects the cramped 25-foot lots of the 78207 from the lofts, the leafy, art-filled riverside promenades, the tail-to-snout eateries, and the brewpubs of the city’s prosperous core.

In this daily school commute up and down Guadalupe Street, parents and students are presented with a vivid illustration of their stark reality: By virtually any statistical measure, San Antonio is the most economically segregated city in the United States. Its poorest neighborhood, the 78207, is located a scant few miles from the epicenter of the third-fastest-growing economy in the country. But as the city as a whole thrives, the residents on the West Side are all but locked out of the boom.

Into this divided landscape three years ago came a new schools chief, Pedro Martinez, with a mandate to break down the centuries-old economic isolation that has its heart in the 78207.

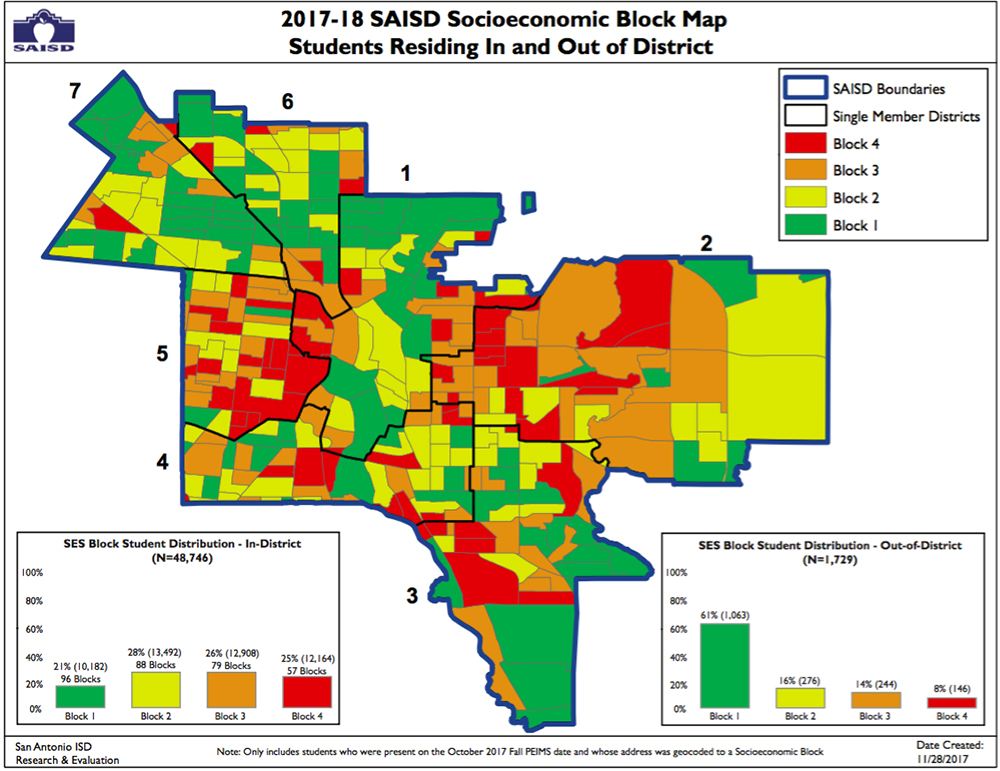

In response, Martinez launched one of America’s most innovative and data-informed school integration experiments. He started with a novel approach that yielded eye-popping information: Using family income data, he created a map showing the depth of poverty on each city block and in every school in the San Antonio Independent School District — a color-coded street guide comprised of granular details unheard of in education. And then he started integrating schools, not by race — 91 percent of his students are Latino and more than 6 percent are black — but by income, factoring in a spectrum of additional elements such as parents’ education levels and homelessness.

To achieve the kind of integration he was looking for, he would first have to better understand the gradations of poverty in each and every one of his schools, what kinds of supports do those student populations require, and then find a way to woo affluent families from other parts of the city into San Antonio ISD schools to disrupt these concentrations of unmet need. Martinez’s strategy: Open new “schools of choice” with sought-after curricular models, like Montessori and dual language, and set aside a share of seats for students from neighboring, more prosperous school districts, who would then sit next to a mix of students from San Antonio ISD, where 93 percent of kids qualify for free and reduced-price lunch.

Only a few years into the experiment, the effort has reshaped the educational landscape, and redefined the aspirations of its students and educators. The district’s diverse-by-design schools now have long lists of well-to-do families waiting for a seat to open up alongside students from working-class households and destitute neighborhoods. Families from the affluent communities on the city’s north and northwest sides are indeed now eagerly applying to share classrooms with families from the 78207.

Student learning has accelerated — in both the new, marquee programs and existing schools.

When Texas released its 2017-18 school performance scores last month, San Antonio ISD, with its 50,000 students and 90 schools, was named one of the fastest-improving districts in the state. The system as a whole had risen from the equivalent of an F rating to a C in just the past three years. Thirty-four of its schools earned the state’s “distinction” designation.

The number of San Antonio ISD schools that would have landed on the state’s “improvement required” list using 2018 criteria fell by half. Using the same calculus, the number of students enrolled in a low-performing school plummeted from 47 percent to 16 percent, the largest decrease among urban districts in the state.

With arguably the nation’s most radical school integration experiment reaping early wins, what Martinez says he needs most now is time — to get his still-disadvantaged schools from a C to an A, to change beliefs at all levels about what success looks like, and to stave off a gathering storm of opposition from those who disagree with his maverick approach.

National experts on school improvement are buzzing about Martinez’s work. But if he is to win over his detractors — and to reach the most profoundly destitute children within a larger community marked by poverty — he needs the same sense of excitement his work is garnering outside San Antonio to catch hold in his own segregated backyard.

74 Films: Inside the SAISD integration experiment:

A boy from the barrio takes charge

Martinez is himself an immigrant from Mexico and a first-generation college-graduate success story. Soft-spoken and trained in finance — not as a teacher — he was a curious hire back in 2015 for the south Texas district.

San Antonio ISD is one of 17 school districts within the city limits, but its blanket poverty is no accident. The district’s boundaries were drawn decades ago to neatly follow the 1940s-era red-lined maps segregating blacks and Latinos into what is now an urban core. By contrast, the district located to the immediate north, Alamo Heights, has a poverty rate of 20 percent.

San Antonio ISD’s school board president, Patti Radle, has lived and worked in the 78207 — the district’s most impoverished neighborhood — for nearly half a century. A former J.T. Brackenridge teacher and community activist, she believed Martinez, like her, would see her neighbors’ pride and resilience, and not fall victim to what she calls “the pobrecito” — “poor thing” — phenomenon.

Radle listened to Martinez describe his family being forced to move every time their landlord figured out how many people were stuffed into their tiny apartment. She became convinced he understood the weight of students’ challenges, as well as the dangers of well-intended but misguided educators trying to protect them from rigorous academic material.

Martinez believed the neighborhood kids could succeed on par with their wealthy peers, just as he had done, and wouldn’t settle for less, she says.

“His attitude and his insight seemed outstanding,” she said.

She and her fellow board members told Martinez his job was nothing less than to create a school system that would serve as a model for big-city districts throughout the nation.

Never mind that these are the marching orders every urban school board chair gives every new superintendent — as the product of a similar community Martinez didn’t hear the directive as a rhetorical one. Neither of his parents made it past second grade, and both worked long hours to feed their 10 kids. At 16, Martinez went to work, too, to help support the family. He knew what creating a generation of college graduates eager to come home to live and work would mean for the 78207.

But knowing that nearly every student in the district was low income told Martinez only the size of the problem, not anything useful in terms of addressing it. In search of better information than what school districts traditionally compile, he turned to census data to create the color-coded map showing the wide variation of levels of poverty from one school to another.

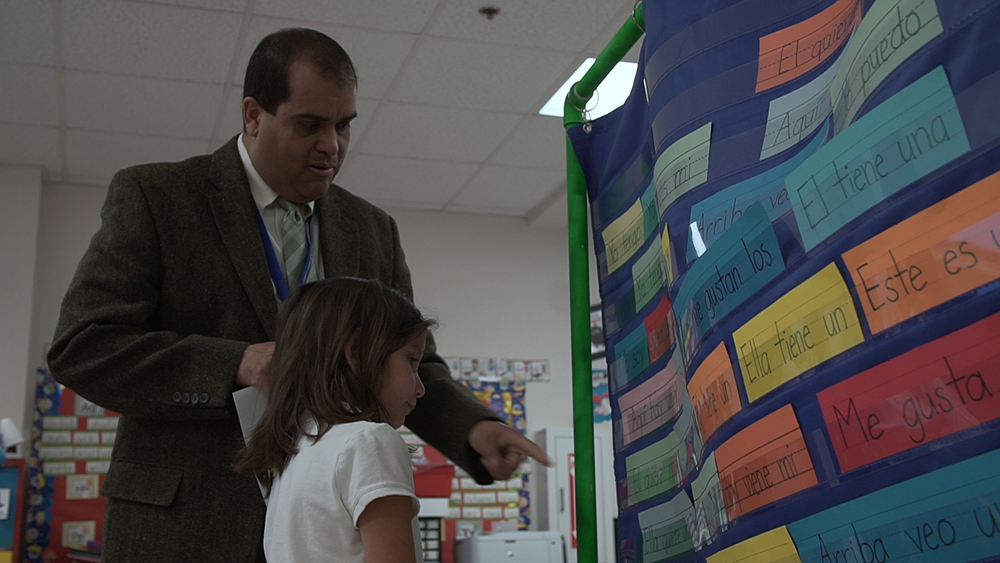

After that, Martinez rebooted dozens of schools, reorganizing them around the kinds of programming — Montessori, dual language, gifted and talented — that families in wealthy communities paid private school tuition for. He recruited master teachers and pushed existing ones to retrain. Lacking the money of neighboring districts, he tapped civic organizations and philanthropies to pitch in.

And he did it fast: “We had to do something completely different,” he says, “knowing we can’t say to the kids, ‘Hey, can you stay home for a couple of years while we retool?’”

Fast-forward three years. Martinez has opened an eye-popping 31 schools of choice. Families — some of them affluent parents who previously didn’t give the district a thought — are clamoring to get their children in. Using what he now knew about the extreme poverty of some of his families, Martinez’s team created a sophisticated lottery system that carves out a percentage of those seats for the neediest students.

Philanthropy is writing big checks. The number of high school graduates going not just to college, but to selective colleges has soared. And Martinez has made sure to build cultural bridges to enable his graduates, many of whom had never before left Texas, to succeed there. In 2017, for example, he organized a road trip to Middlebury College in Vermont so the families of four San Antonio ISD students got the chance to settle their kids in at the elite liberal arts school, while catching a glimpse of what life is like in such an unknown setting.

The education world took note. In February, the Center on Reinventing Public Education brought dozens of leaders of cities that are home to large, struggling school districts to San Antonio to tour the new schools and to hear how Martinez managed to raise the bar so fast — and on a shoestring.

The center’s director, Robin Lake, credits Martinez’s willingness to listen to what the community wanted and to build first on its strengths for the quick buy-in he got. “He really took the time to hear about what was missing in kids’ educations,” she says, and to learn what would empower teachers.

“Going barrelling forth with a top-down solution the community isn’t going to feel good about is the past,” Lake adds, referring to a common criticism of some education reform efforts. “Listening to the community and creating the things they want is the work of the future.”

It appeared Martinez was well on his way to fulfilling his marching orders. But change agents have a way of attracting headwinds.

Last winter, the 48-year-old schools chief announced a plan to invite a charter school network to take over a struggling elementary school slated at that point for closure by the state. Almost overnight, the San Antonio Alliance of Teachers and Support Personnel declared war. The union filed a lawsuit. Critics vowed to oust the school board that hired Martinez. Posters appeared on telephone poles with the hashtag #byepedro.

Now, a new challenge looms. Can Radle and her school board colleagues stand firm, mustering enough support for Martinez’s efforts to continue to spread beyond the impoverished but gentrifying and historic parts of the district where San Antonio ISD’s most successful new schools have opened? Can families have the same excitement and progress in its most profoundly isolated neighborhoods, in schools like J.T. Brackenridge? Can they change expectations fast enough to interrupt generations of complacency?

Martinez and Radle say they have to if they are to create a system that is, in fact, a national model for breaking down the economic segregation handicapping poor children in every big-city school district in the country.

The map that changed the integration conversation

When Martinez was a toddler, his 2-year-old sister died, a tragedy that could have been prevented if his family had access to decent health care in Aguascalientes, Mexico. His father, Rodrigo, orphaned and forced to drop out of school in second grade, realized his family needed to leave if they were to do more than subsist. Rodrigo moved to Chicago and for two years saved money to bring Pedro, his mother, and his surviving siblings north. The local parish helped the family get on its feet, but Rodrigo always had to work two jobs and never earned more than $7 an hour.

In sixth grade, Pedro had a teacher who was determined to push him to live up to his potential. The tough love was effective, and Martinez entered Benito Juarez High School with 12th-grade math skills. He started high school in a class of 700. By the time Martinez graduated, there were 170 seniors left.

He had worked his way up to assistant manager at McDonald’s, but Martinez knew he could do much, much better. He took a leap of faith and enrolled in college, earning a degree in accounting at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and then an MBA at Chicago’s DePaul University.

Martinez was working in finance for the Archdiocese of Chicago when Chicago Public Schools Superintendent Arne Duncan recruited him to work for the district. After serving as its chief financial officer, in 2012, he was named deputy superintendent of Nevada’s Clark County Schools, the nation’s fifth-largest district, then superintendent in Reno, Nevada, and finally, superintendent-in-residence at the Nevada Department of Education.

Watch: One on One with Superintendent Pedro Martinez:

When he visited Radle’s 78207 neighborhood, Martinez was struck by the same things other newcomers are: streets no wider than alleys where houses the size of garden sheds slump, rotting into the ground because there are no sewers to prevent frequent flooding.

“What I saw in my (district’s) neighborhoods were homes that hadn’t had air conditioning in decades,” he said. “And this is a community where the weather reaches 110 degrees with humidity for several months of the year.”

Then there is the street in the 78207 that Radle calls “the place where the money ran out,” a series of intersections where modern infrastructure simply quits, the sidewalks disappear, and roads sporting as much grass as asphalt narrow from two lanes to one.

Martinez thought he knew poverty, both personally and as a professional committed to eradicating it. But what he saw in San Antonio was familiar and yet shocking. The tight-knit families and their warmth reminded him of the neighborhood where he grew up. But the scope and depth of the need was stunning.

“This is the first time that I experienced a district where the entire district had such a density of poverty,” he says. “I could see very quickly because of the demographics of the children and the poverty levels, the density, that we needed to understand it in a deep way.”

Median family income in San Antonio ISD is $30,363. One in five adults aren’t high school graduates, and 42 percent don’t work. Half of the students live in single-parent households. Constant evictions mean up to 40 percent of students shuffle from one school to another.

As daunting as those realities are, the challenges facing J.T. Brackenridge are greater. Located in the poorest corner of the poorest zip code, median family income at the school is $17,000 a year. But J.T. Brack, as residents affectionately call it, enrolls students whose family income dips below $8,000 a year. As a square on the map, the school’s attendance boundary is tiny yet dense, containing three public housing projects, including Alazan-Apache Courts — one of the nation’s oldest, completed near the end of the Great Depression thanks to the parish priest’s relationship with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

Martinez knew that the traditional way of measuring student poverty — tallying the number of children who qualify for free or reduced-price school lunch — was wholly inadequate when it applies to virtually every student in every one of his 90 schools.

At schools near the upper range, an annual income of $45,500 or less for a family of four, students might need extra support in learning basic math and literacy skills, for example. While at schools like J.T. Brackenridge, students need backpacks full of food to take home to their families.

“Our goal is to show our staff, this is what it means to prepare our children for the next level. How do we show parents like mine, who had a second-grade education, what is possible?” —Superintendent Pedro Martinez

To draw the fine-grained portrait he needed, Martinez culled from a different set of data, the U.S. Census’s American Community Survey, which calculates median family income by city block. Cross-referenced with individual student enrollment records, that gave him a median household income level for each school. He put the information on a map, color-coded according to the census’s four corresponding income “blocks,” with Block Four the poorest.

“These are my families that make under $20,000 a year,” Martinez explains. “They are single-parent households, they don’t own a home, and most of the parents don’t have any kind of education beyond high school. In fact, we have in some neighborhoods, a very high percentage of illiterate adults.”

Education research that isn’t based on meal-subsidy data is scarce. But a working paper released shortly after Martinez created his map confirmed his hunch that the depth and nature of poverty matters in terms of a child’s educational odds.

In July 2016, professors at Syracuse University and the University of Michigan used Michigan data to determine the number of years individual students were eligible for free and reduced-price meals. At the time of the study, these students made up half of Michigan eighth-graders.

In “The Gap Within the Gap,” Katherine Michelmore and Susan Dynarski determined that students whose family income was nearest the maximum for eligibility were most likely to be “transitorily disadvantaged” — temporarily set back by a layoff or some other factor the family could bounce back from.

Meanwhile, 14 percent had been eligible their entire time in school. “Persistently disadvantaged,” their families were unable to climb out of poverty. They were more likely to go to urban schools with high concentrations of poverty than their less-impoverished peers. As a group, the poor students studied were about two grades behind their wealthier peers, but the persistently disadvantaged children were three grades behind.

Martinez knew that at some of his schools virtually all of the students carried the trauma associated with growing up in this kind of deprivation. He would have to ask both San Antonio ISD staff and the civic and philanthropic groups eager to contribute to commit to providing the extra support necessary to address this intergenerational trauma.

Martinez carried his map around to Rotary Club breakfasts, meetings with teachers, and any other gathering where it might spark discussion. When he took it to other parts of San Antonio, he pointed out that their poverty bore little resemblance to that of his district. When he showed it within the district, he flagged the outliers.

J.T. Brackenridge was one of them, very near the bottom in terms of poverty but not academic performance. In fact, the school had a higher percentage of students scoring “advanced” on annual state reading and math assessments than the lone district school with median family income anywhere near the national average, about $54,000.

Martinez and Radle had some hypotheses about this. For starters, the close relationships in the 78207 can keep things like evictions and job losses from being as catastrophic as they might be. Though it has since experienced some turnover, the school had an unusually stable staff, Radle notes, and with periodic exceptions, the neighborhood experienced much lower crime rates than might be expected.

Usually when Martinez highlighted the surprises on his map — J.T. Brack’s scores were decent, but the district’s Young Women’s Leadership Academy was one of the best schools in the country in terms of academic achievement among low-income children — people would ask why. What went right, and could they build on it? And if kids were learning in the elementary years, how come college enrollment and graduation were still so elusive?

Conventional wisdom is that multi-generational poverty is the cause of low academic achievement. It’s undoubtedly true that decades of inequities in places like San Antonio’s urban core have created devilishly tough circumstances. But as people who also see the richness in the 78207 and similar communities, Martinez and Radle agreed that beliefs about poverty — the pobrecito problem — are also a very real barrier.

Martinez understood that to parents with little experience beyond their isolated neighborhood, the payoffs from a quality education aren’t tangible. If you don’t know anyone who has a college degree or a comfortable salary, you literally can’t envision how to get those things.

“Our goal is to show our staff, this is what it means to prepare our children for the next level,” he says. “How do we show parents like mine, who had a second-grade education, what is possible?

“I came to the conclusion very quickly that if I didn’t change that conversation that we were going to have this cloud of low expectations and it was going to continue,” Martinez adds. “Our first goal was to redefine excellence.”

Reporter’s Notebook, Animated: ‘In 20 years of failed integration efforts I’ve never seen anything like this’

Integrating by income — when 93% are in poverty

A few months after he arrived in San Antonio, Martinez approached the principal of the most academically successful school in the metro area, the International School of the Americas. Would Kathy Bieser leave her prosperous north-metro school district to design and lead a school in San Antonio ISD?

And not just any school. Martinez wanted to create a gifted and talented academy that would be open to any child in the district, regardless of test scores or zip code. The plan had multiple layers.

There’s a trove of evidence that one way to increase student achievement is to offer more challenging academic material. Requiring students to think critically about knowledge gleaned across different subject areas, the approach used in gifted and talented programs, is precisely the kind of “higher order” learning now shown to be invaluable in raising academic achievement. But when it is offered at all, it’s typically reserved for children who already are ahead. Screened infrequently, children of color are rare in gifted and talented programs.

With 93 percent of his district’s students impoverished, the only way Martinez could create socioeconomic diversity in schools was to attract families from more affluent communities. Convinced a gifted and talented program would be an immediate draw, Martinez would reserve 25 percent of seats for students from other districts.

Dissatisfied with offerings in even the most prosperous traditional districts, San Antonio families of means were decamping for private schools or for one of the nation’s most rapidly growing charter school sectors. Several of the charter networks expanding in the city, such as IDEA and KIPP, have reputations for being academically challenging.

Bieser was well positioned to set a high bar, certainly, but Martinez had another reason for tapping her. The school where Bieser was principal had been conceived of as a teacher-training lab for nearby Trinity University, whose school of education is one of the best in the nation. Hard-pressed to compete financially for teachers, Martinez needed a “grow-your-own” talent pipeline.

The newly created Advanced Learning Academy would have a partnership with the college, which would place 10 educators-in-residence and four would-be principals in the school each year. Instead of a few weeks of student teaching at the end of their educations, the teacher-in-training would spend an entire year working side-by-side with master teachers.

Because the pairs continually talk through the choices they are making in the classroom, in Bieser’s experience, residencies are beneficial not just to the student teachers, but to their veteran mentors, too.

“The magic involves being present at the very beginning of the school year almost to the very end of the school year,” she says, “seeing the flow of the year and having a classroom as well as a school that’s deeply reflective. And so not only the resident, but that master teacher, that mentor teacher are all the time kind of talking out loud about their craft.”

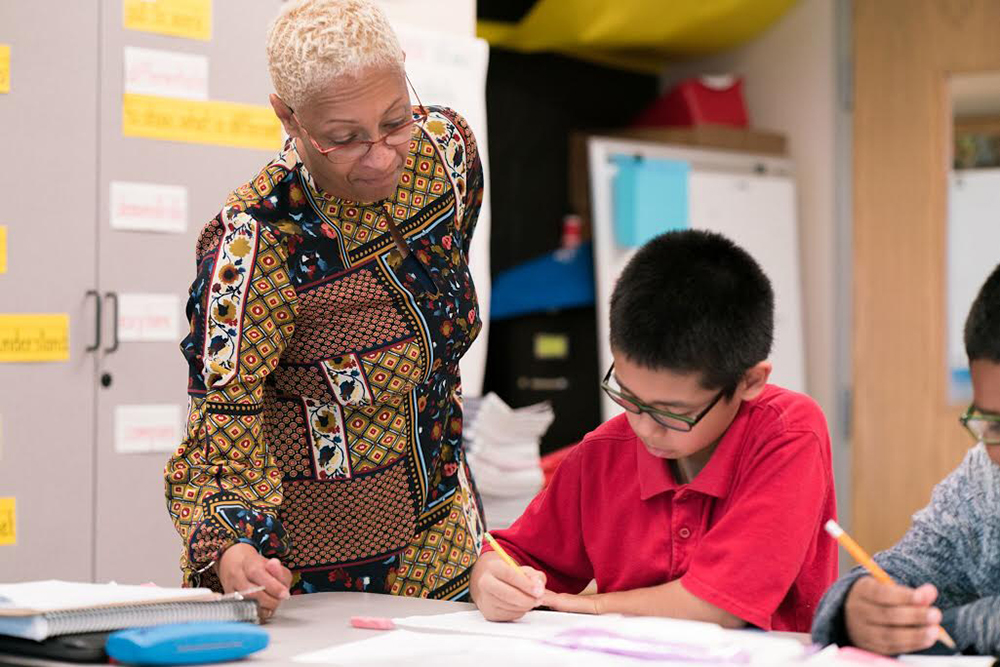

San Antonio ISD would pick up a large portion of the cost of training if the new teachers agreed to stay in the district for several years. Significantly, when they completed their residencies, they would take the high expectations of the gifted and talented model with them to other district schools where few believed impoverished students would benefit from academic rigor.

Advance Learning Academy had a waiting list even before the first day of school in August 2016. Encouraged, Martinez rolled out the welcome mat, offering to reopen schools mothballed because of declining enrollment for teachers and principals interested in creating new schools with dynamic models.

He had no shortage of takers. When the 2017-18 school year started, San Antonio ISD boasted a dual language program, a Montessori school, high-tech and early-college high schools, a teacher-residency school run by the Relay Graduate School of Education, and a number of specialized programs within existing schools. This year, a third dual language school came online, along with an all-boys school and a host of other new programs.

“We’re seeing again such a great response from our families. We have 10,000 applications right now for 3,000 choice seats in our district. We’ve never seen that in the history of the district,” Martinez says. “What I’m very hopeful for is that I’m seeing a community movement. I’m seeing conversations change.”

But with success came a new challenge. As applications rolled in for seats in Advanced Learning Academy’s second year, they followed a trend common throughout the country: As soon as a new school acquires a buzz on the parent grapevine, middle- and upper-class families can quickly dominate.

“We love the fact that our schools are becoming popular, but could we create our own problems?” Martinez asks. “Could we further segregate our own families just based on our success?”

Martinez needed to make sure families from Block Four, the poorest of the poor, got their share of seats in the new schools. He recruited a former teacher who was trying to create “diverse by design” schools in Dallas, Mohammed Choudhury, to start and lead an Office of Innovation.

Choudhury, whose Twitter bio lists desegregation as a job duty, immediately began creating an enrollment system that would reserve seats not just for out-of-district families and neighborhood residents, but for children from each of the income “blocks” on Martinez’s map. And he dug even deeper into the data to incorporate information about parents’ educational attainment, home ownership, single-parent status, and other factors.

Without careful controls, Choudhury says, school choice can create “islands of affluence.” So for the 2018-19 school year, one-fourth of the 3,000 open seats in the 31 choice and magnet schools were reserved for students with the highest needs.

And he and Martinez are working to locate new innovative schools in neighborhoods where geographic and economic isolation make school choice an abstraction.

Living in two worlds

One day last spring, as she was driving past J.T. Brackenridge, Radle spotted a former student of hers, Priscilla Lucio, on the way home from picking up her son, Carlos Zuniga Jr., from school.

“You don’t have, like, beans on the stove or anything like that do you?” Radle asked, making sure they had time to talk.

“No,” Lucio replied. “I did but I took them off.”

The boy, better known as C.J., had just been accepted into a new engineering program at Lanier High School, Lucio told Radle. They had gone to visit and C.J. had become captivated with the idea of working on jet engines. He’s never been on a plane, but if he had the chance, he said, he’d fly to Tokyo.

Lucio had dreamed of being a pediatrician but dropped out in 11th grade when she became pregnant with C.J. The visit to Lanier’s high-tech program changed what she wanted for her first-born.

“At first, growing up and having him, I would say, ‘Oh, I want him to join the (armed) services,’” she said. “But now, I think there’s more out there in life than just that … I would love for him to go to college.”

How would C.J. feel about leaving? How would his family? At this, the talk became more tentative. “It would be hard for my mom to let me go to college just for the fact that I’m the oldest and I’m the first one to go,” C.J. says, looking at his feet and not at his mother.

Named one of the 25 most influential Latinos in the United States by Time magazine, Lionel Sosa is a celebrated native son of the 78207. He has advised presidents and the heads of Fortune 500 companies, and yet he is intimately familiar with the shift of perspective Lucio and her children are undertaking. At 79, he has 50 grandchildren and great-grandchildren, many of whom live in the neighborhood.

Sosa’s own kids are from two marriages, the first to a woman who did not finish high school and the second to a college graduate he married after he made a fortune in advertising. His first four children didn’t graduate from high school. The next two graduated from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and Yale University.

“I live in these two worlds,” he says. “A world where there was no education, and life has been tough, and a world with education, that’s not quite as tough.”

Just three of the 180 members of Sosa’s own Lanier class went to college. “At the time, the courses they offered to high school students were paint and body shop, carpentry, printing, body and fender, upholstery,” he says. “They were preparing the Mexican kids to do the work that Mexican kids should do.”

San Antonio ISD offers much more now, but Lucio and C.J. have another leap to make, Sosa says. Mexican-American culture prizes family. Bringing home a paycheck, however slender, and having one’s own children is being a good son or daughter.

Sosa intervenes now when he learns a grandchild has been accepted to college but is waffling, pointing out as many times as it takes how much more college graduates can contribute and arranging to visit the campus together to help iron out things like financial aid.

Home, Radle knows after watching generations of the 78207’s young people struggle with this moment, exerts a powerful pull. Contrary to stereotypes about poverty, it’s a place where people lift one another up, sharing whatever they have and always making time to catch up. On seemingly every corner of the 78207, there’s art celebrating the neighborhood’s heritage.

And yet, as the rest of the city prospers, the West Side is backsliding. As she cruises the neighborhood, Radle can’t help but notice where homes, their foundations rotted away by rainwater, have literally fallen down.

“Just a few years ago, there were houses there that were very run down,” she says, gesturing at empty lots on a street the city started to redevelop several years ago but never finished. “But at least it was someplace for people to live.”

Fifty years ago, C.J.’s great-great grandfather was one of the founders of Inner City, the neighborhood nonprofit Radle co-directs with her husband, Rod. That work — all volunteer — has helped to keep the community’s culture vibrant, despite its hardships. But it hasn’t been enough.

Like Sosa, Radle knows how much C.J.’s family needs him to leave for at least a little while if meaningful change is to make it over the economic and social moat that encircles the neighborhood. As she watches him start to hesitate at the thought of going away to college, she jumps in, pointing out the things he could fix if he comes back to the 78207 as an engineer.

C.J. brightens. “If I had a degree, it would mean a lot to me,” he says. “I would have money and I’ll help them out to buy them a house, or buy them a car or something. I’ll try to help out and get them what they need like food, or water, or clothes. I’ll just help around with my family, my grandmother, my tia, my grandpa.”

Once C.J. has had a taste of financial security and the opportunities it can open up, Sosa is confident he will begin thinking about even larger contributions — to his family but also to the future of the 78207.

“In the Latino community, and the Hispanic community, helping family is what life is all about,” says Sosa. “It’s not about helping yourself, or doing well for yourself. It’s about the family doing well together.

“But many folks take the wrong turn in how to help their family,” he adds. “They drop out of school early, they go get a job, and then remain in a low-paying job all their lives, creating yet another generation that’s living in poverty, or close to poverty.”

No one, Sosa says — not his family and not San Antonio — can afford that.

“That’s got to change.”

Every data point a child

In 2015, the Texas Legislature passed a law requiring the state Department of Education to take action when a district has one or more schools whose low test scores have placed them on the “improvement required” list for five or more consecutive years. The department must either close the schools in question, the bottom 5 percent of the state’s public schools, or take away power from the local school board. (Charters are considered school districts for the purposes of the law.)

Two years later, lawmakers added a third option: A district could forestall state action for two years by turning a school with five “improvement required” ratings over to an outside partner, including networks of charter schools, nonprofits, or universities.

For the first of these struggling schools, 2018 is the year the clock runs out. With six affected campuses in 2017, San Antonio ISD had more than any other district in the state save Houston, which had 10 schools on the list. When the state released the 2018 list in August, four San Antonio ISD schools had improved enough to climb off it. A fifth escaped sanctions because it is now run by a teacher-training program, and the district announced it would close the sixth school.

In January, Martinez announced plans to contract with Democracy Prep, a New York-based nonprofit charter network, to run P.F. Stewart Elementary, one of the persistently low-performing programs. The district chose the network, which also has schools in Washington, D.C., Louisiana, and New Jersey, because of its strong track record. Its first New York City program opened in 2006 and by 2009 had become the city’s highest-performing middle school.

The San Antonio Alliance of Teachers and Support Personnel protested at a March board meeting where the agreement with Democracy Prep was approved. One speaker threatened “open season on board members.” Soon after, the #byepedro flyers began appearing throughout the district and the union sued.

“School superintendents and school boards are not above the law, which is designed to protect the best interests of school employees as well as students and parents,” union President Shelley Potter said in a statement. “School teachers, staff, our students’ parents, and the community were ignored in the district’s haste to turn over a neighborhood campus to a New York charter company with no ties to our community.”

Pouring kerosene on the fire, enrollment declines and past overstaffing at the district’s non-choice schools required laying off some 130 teachers and classroom aides, a process Texas law says can incorporate performance evaluations.

It’s common for teachers unions to protest district collaborations with public charter schools, especially when the partnership exempts a school from the local bargaining unit’s contract. But San Antonio ISD oversees 20 in-district charter schools, including Advanced Learning Academy — the first specialized school Martinez created — and a number of other popular new programs.

Braination, a local charter network, runs a school for the district’s most challenged special education students, and another, Texans Can Academies, a dropout recovery program. The San Antonio campus of Texans Can, which serves students who are older than their classmates or have too few credits for their age, has a dropout rate of 6 percent, compared with 39 percent among the same population at some San Antonio ISD high schools.

The difference between the new partnerships and the charters the union has not protested is a bread-and-butter distinction: The new schools employ their own teachers, while the district’s choice schools are staffed by San Antonio ISD employees, albeit on terms that differ from the rest of the district.

Democracy Prep’s contract with the district gives it room to expand if it’s successful, eventually enrolling two K-12 “continuums,” each consisting of an elementary, middle, and high school. Current Stewart Elementary staff who are not hired by Democracy Prep can choose to stay in the district and be assigned to other schools.

Whatever the trajectory of the competing pressures created by the school-closure law, the chapter threatens to engulf Martinez in a swirl of controversy that his backers fear could erode the political capital and good will that have enabled him to make so many changes in such a short time.

When Texas released its 2018 school performance data in August, Martinez got lots of good news. The percentage of San Antonio ISD students meeting or exceeding expected growth in reading and math rose to 61 percent, from 53 percent in reading and 52 percent in math the year before. The district saw academic gains across grade levels and on 73 percent of its campuses.

“Every one of those data points is a child,” Martinez says, adding that the state singled the district out as one of Texas’ fastest-improving school systems. “Those children are growing academically and their teachers’ hard work is paying off.”

Has the community had a big enough taste of success to support him, and Radle’s board, in continuing with their experiment?

“We need time to build this out,” says Martinez. “What I tell my [board] is, ‘You have to think 20 years out.’ These things have to outlast us. Will these systems become so popular people don’t look back?

“The need has been here for decades, that hasn’t changed,” he adds. “What’s different is we’re showing people what’s possible.”

The Architect — On the poor side of a deeply divided city, one ‘diverse-by-design’ prophet is weeding out school segregation, one equity audit at a time

Mohammed Choudhury grew up in Los Angeles, “a minority amongst minorities.” His parents emigrated from Bangladesh in the 1980s, a moment he sees in retrospect as an easier time for immigrants to establish themselves. His parents saved up, opened a restaurant in West Hollywood, and worked their way into the middle class.

They sent their kids to the neighborhood school, which had students from all over the world, something Choudhury loved. He knows now, as a rising star in education leadership, that it was academically lackluster. But from his parents’ perspective, the school was the gateway to the self-determination they came to the U.S. seeking.

“For my family, and on my dad’s side especially, it was a big deal for us to be educated,” he says. “It was a privilege in Bangladesh.”

Choudhury came to understand that firsthand. In fifth grade, he was taken to visit the village where his paternal grandfather built the first school in 1953. Back then, only children from wealthy families went to school. Otherwise, if you were born in a village, your future was preordained.

“When my grandfather built that school, he basically flipped that concept on its head and said, ‘We can access education here,’” says Choudhury. “I grew up under that upbringing, that it matters. And to me it was more about agency.”

Fast-forward not so many years, and Choudhury, 34, is leading a closely watched effort by the San Antonio Independent School District to open dozens of innovative new, diverse-by-design schools. Because virtually all of the district’s 50,000 students are impoverished, to create that diversity he must both attract affluent families from outside the district and ensure that children from the most isolated, destitute families within it are represented in these exciting new schools.

After decades of shrugging over the seeming impossibility of desegregation, many communities are responding to renewed interest in paying more than lip service to school integration. In this context especially, Choudhury’s work has drawn national attention.

“When I heard Mohammed was joining the team in San Antonio, I wasn’t surprised,” says Mike Magee, CEO of the nonprofit state and district superintendent network Chiefs for Change. Choudhury, he says, is “one of the leading national advocates and experts on creating diverse-by-design public schools as part of an overall equity strategy.”

Half a world away from Bangladesh, San Antonio has repeatedly been named the most economically segregated city in the United States. Its most impoverished communities are not villages, but their geographic isolation and profoundly inequitable school systems have their roots in early decisions to segregate blacks and Latinos on small, dense tracts of land.

There are 17 school districts within the city, catering to communities of differing levels of prosperity. San Antonio ISD serves the urban core made up of those red-lined neighborhoods — which means Choudhury is attempting to integrate schools where more than 90 percent of students are economically disadvantaged, according to the federal definition, and almost all are Mexican-American.

Choudhury’s work, then, is different from what most people envision when integration is talked about. Traditionally, districts that are pursuing desegregation are drawing attendance boundaries and taking other steps to get children of different races and ethnicities into common schools.

It might be on a different continent and a lifetime later, but Choudhury is fulfilling his family’s legacy in creating schools where education can serve as a means to self-determination.

“I am a proud product of an urban school district,” he says. “My family is that story of the American dream.”

‘A few winners and lots of losers’

School in California provided Choudhury with the mobility his family hoped for, but it also served him lesson after lesson in how unequally those opportunities are distributed. In high school, he was tracked — sized up and placed in a magnet school for students who were deemed college material.

“I knew there were other tracks that weren’t because I had friends that I hung out with,” Choudhury recalls. While they were taking math classes that didn’t count for anything, he was taking algebra, trigonometry, and calculus. The gap in aspirations made him uncomfortable.

One day, his high school held a career fair where he met a sociologist. “I thought it was the coolest thing that they just study problems,” he says. “You figure out what the underlying root causes were, you promoted a solution or you gave solutions, and you solved it.”

He set his sights on UCLA but didn’t get in. Determined, he bypassed the University of California schools that did admit him and enrolled in Santa Monica Community College, which had a path for feeding students to UCLA. After earning his bachelor’s degree there in English and Chicano studies, he went into the education program to train to be a classroom teacher.

Choudhury taught in several Los Angeles Unified School District schools, helping to turn around Luther Burbank Middle School, a chronically low-performing school that rose to be named a state “School to Watch.” The district’s magnet schools were terrific, but he was frustrated with the lack of opportunity outside of them. He could do more for more kids, he decided, in a position where decisions were being made.

“I said, ‘I need to get into those rooms,’” he says. “And that eventually led me to be obsessed with school design and redesign and with how enrollment works.”

WATCH — Innovation czar Mohammed Choudhury on designing schools for diversity:

In 2014, Choudhury was hired to help the Dallas Independent School District develop 35 new or rebooted schools organized around teachers’ interests. The first new schools were quickly oversubscribed, drawing some 1,600 applications for 617 seats for the 2016-17 academic year.

Inevitably, affluent families flocked to the schools. The district came under pressure to give admissions priority at one — an all-girls engineering-themed school — to children from the surrounding very wealthy neighborhood. No way, said Choudhury. That would simply re-create the segregation wrought by housing patterns.

“One of the things that we told ourselves is we’re not going to do school choice … in a way that exacerbates segregation,” he says. “We’re not going to create a system [that has] our hands and fingerprints on it that allows a few winners and lots of losers.”

Three elements for success

When the district got a new superintendent, Choudhury started looking for his next gig. He was thinking about going to work for the state of Texas or maybe returning to California when he got a call to meet San Antonio ISD Superintendent Pedro Martinez. The south Texas district was a third the size of Dallas, and Choudhury was determined to continue implementing his integration vision.

Motivated by a desire to show teachers and families alike that San Antonio ISD could achieve academic excellence with the poorest, most challenged students, Martinez had already started a gifted and talented school to serve as an incubator of teaching talent and opened it to children of any ability. Choudhury sensed a kindred spirit.

“One of the things, if he was going to pick me, diverse by design was going to happen,” says Choudhury. “That’s non-negotiable to me. He was like, ‘Absolutely.’ He grew up in Chicago, he understands how things played out in the magnet schools.”

Martinez, in turn, was attracted to Choudhury’s insistence that school choice must be accompanied by mechanisms that ensure equitable access for all families, something he wishes had been in place during his time in Chicago.

“It gives me a lot of comfort to know there is someone watching out for that who shares my values and is so passionate,” says Martinez. “Often, when district leaders discuss choice options, there are unintended consequences for parents, and Mohammed is dedicated to understanding families’ needs.”

Martinez says his chief priority for Choudhury is the creation of systems. “The longer strategy that will take some time is taking these strategies and replicating them,” he says, explaining that Choudhury’s brand-new Office of Innovation will oversee this.

“I believe Mohammed’s leadership is already showing those changes,” Martinez says.

Three elements are indispensable in creating a system of schools that’s equitable and sustainable, in Choudhury’s view. The first is schools with attractive themes or instructional models, such as Montessori or dual language, in accessible locations. Then there’s transportation; without busing, the most desirable schools will fill up with families that can transport their own kids.

Finally, districts should create one unified enrollment system and use it to weight enrollment at each school for diversity. Families that don’t get their first choice in a computerized lottery should get help finding the next-best fit for their child, and the admissions process should include equity audits to ensure that the most isolated students are adequately represented.

He’s right, says Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, which in February invited leaders from 16 cities around the country to visit San Antonio and learn about Choudhury’s and Martinez’s work.

“When there is more choice in a community, there is always a risk of sorting and segregation,” she says. “Cities that I have seen that have taken enrollment challenges really seriously have done the hard work of going out and doing that kind of education.”

Addressing poverty, “block” by “block”

Installed as San Antonio ISD’s first chief innovation officer in February 2017, Choudhury picked up a project Martinez had started upon becoming superintendent in 2015. School districts and education policymakers almost always quantify poverty according to the number of students who qualify for free and reduced-price lunch, the family income data point collected universally. But that statistic isn’t useful when it applies to virtually every student in the district.

For a family of four, that threshold is $45,500 in most places — nearly twice the federal poverty level and much higher than the $30,000 median income of San Antonio ISD’s families. Using much more nuanced and precise census data, Martinez had created a map listing median family income at all 90 schools in the district. Some were as low as $12,000 a year.

Choudhury mined deeper into the data, layering parents’ educational attainment, single-parent household status, homelessness, and other information into four census income “blocks.”

The gifted and talented school Martinez had launched, Advanced Learning Academy, had a waiting list even before it opened. As the superintendent intended, a fourth of the students were from outside the district. And, as is the case whenever a school acquires a buzz, applications for its second year skewed even wealthier.

Complicating things further, some of San Antonio ISD’s most popular offerings are dual language schools. Many of the city’s Latinos were forced to give up their Spanish because of past beliefs that children should assimilate. The district’s new bilingual schools are to be integrated not just by Choudhury’s socioeconomic blocks but also by home language status.

Similarly, a new Montessori program with a focus on inclusion aims to enroll pupils with disabilities, a particularly underserved population in Texas, which earlier this year was found to have improperly denied services to tens of thousands of special-needs students. In the wake of a Houston Chronicle investigation, the U.S. Department of Education confirmed that state officials had imposed a cap on how many students local districts could classify as being eligible for special education.

Meanwhile, the new, high-tech CAST Tech High School enrolls fully half its students from outside the district. In its first year, CAST earned a state “distinction” designation, meaning it outperforms similar programs.

All of this means Choudhury will need not just to conduct an admissions lottery for each school where there are more applicants than seats, but to control for other student socioeconomic factors, depending on each school’s desired makeup. Like other districts with centralized admissions systems, his office uses a computer algorithm to run lotteries.

Because district “choice” schools reserve seats for different socioeconomic groups, admissions officers either run multiple lotteries until all seats are filled or, in the case of schools with waiting lists, go down them in numerical order until they find a suitable applicant. The district’s dual language schools, for example, receive more applications from English-dominant households than Spanish-speaking ones and so tend to admit most or all native Spanish speakers who apply.

To preserve the 50-50 home language balance at a dual language school, for example, San Antonio ISD leaders might bypass students atop a waiting list if they are from English-speaking families and instead admit the first student on the list from a family of native Spanish speakers.

Special attention will have to be paid to making sure that children from the poorest census blocks, Blocks 3 and 4 in Choudhury’s system, apply and get in. Poor though they are, families in Blocks 1 and 2 are more likely to have two parents with at least one stable job and to be literate, all factors that make them more likely to undertake the process of choosing a school.

The system is working at CAST Tech, where 71 percent of students from outside the district come from San Antonio ISD’s highest-income “block,” versus a fourth of students who live in the district. Half of CAST Tech’s in-district students come from the more disadvantaged and poorest families, the bottom two income blocks.

The most fragile and isolated parents are not likely to realize they have options or to have the context to analyze them without support.

“The Montessori program we have, one of the toughest battles is convincing them that it’s a school that’s not selective admissions, and their child can thrive in it,” Choudhury says. “It’s going to be a constant battle to shift that narrative.”

San Antonio ISD enrollment staff will fill out applications for families over the phone and regularly sets aside time to knock on doors in the poorest neighborhoods. For families who don’t win the lottery, district staff call to let them know about similar schools with open seats or new programs closer to home.

Finally, Choudhury’s system gives extra weight to applications from children attending Texas’s lowest-performing schools, the ones on the state’s “improvement required” list. In 2017, 19 of the district’s 90 campuses were on the list, but 35 would have qualified if new, higher state standards implemented this year had been in force. In 2018, the number of schools on the list fell to 16.

Fighting the resegregation tide

In the decades since court-ordered integration plans of the 1970s and 1980s lapsed, most communities have returned to systems of neighborhood schools, which enroll students according to segregated housing patterns.

One-third of black and Latino students go to schools that are 90 percent or more nonwhite, according to The Century Foundation. The reverse holds true for white children: More than a third attend schools that are virtually all-white.

Meanwhile, as courts have restricted schools’ ability to integrate based solely on race or ethnicity, a number of districts and charter schools have experimented with integrating according to socioeconomic status.

Until 2010, Wake County, North Carolina, had a widely lauded program of integrating schools economically by grouping relatively impoverished schools in Raleigh and more affluent schools from 11 surrounding suburbs into a single large district. The program ended in a political backlash fueled in part by transportation issues, school schedules, and funding disputes.

A similar socioeconomic integration scheme in Kentucky’s Jefferson County, which encompasses Louisville, has remained in force despite assaults from state lawmakers. Some charter schools, which in most places must admit by blind lottery, recruit from diverse communities.

But those efforts have relied on the voluntary participation of wealthy suburbs adjoining impoverished cities. San Antonio ISD, by contrast, is going it alone.

“It may not be perfect out of the box,” says Lake, of the Center on Reinventing Public Education. “But the commitment I’ve seen from that team suggests they’ll keep refining and pushing until they get it right.”

And they will keep pushing, if Choudhury has his way, to make sure the system is successful enough that future leaders would be foolish to water it down.

“What keeps me up at night is that I will not be able to build a system that prioritizes equity that can last beyond Superintendent Martinez, myself and the current board members,” he says. “I have told my team and I continue to tell them, ‘Design as if you won’t be here one day.’ That’s what keeps me up at night.”

Expanding School Options (and Horizons) — How SAISD is partnering with top charter networks to give parents both in and beyond the 78207 new choices

Over the summer, Families Empowered, a nonprofit group that helps Texas families navigate their school choice options, revealed an eye-popping number. For the 2017-18 school year, San Antonio families submitted nearly 40,000 applications to the city’s three largest charter school networks: Great Hearts Texas, KIPP San Antonio (now KIPP Texas), and IDEA Public Schools.

Six years ago, those networks combined enrolled some 800 San Antonio students, according to Choose to Succeed, a group working to attract charter schools to the city. Today, the organization puts the number of students in schools it supports at 16,600. The goal is 60,000 by 2026.

With 1.5 million residents, San Antonio is already the seventh-largest city in the country and is estimated to grow by a million more people in the next 10 years, says Choose to Succeed CEO Christopher “Chip” Haass.

“Our goal is to increase high-performing [school] seats as fast as possible,” he says. “We wanted to make sure San Antonio was on the radar for these high-performing schools.”

Opinions about school choice notwithstanding, what these numbers add up to is a tidal wave of change aimed directly at one of the nation’s fastest-growing and yet most economically divided cities. An unconventional leader, San Antonio Independent School District Superintendent Pedro Martinez has responded by engaging his would-be competitors, creating in-district charter schools that are proving wildly popular, making sure the most impoverished kids are fairly represented in them, and asking everyone to push toward the same goal as the charter schools: making sure all students are college-bound.

A year and a half ago, Ambika Dani arrived in this volatile landscape, intent on opening a public charter school. Her plan was for Promesa Academy Charter School to serve elementary-age pupils in the city’s most impoverished zip code. Four of the nine elementary schools located in the 78207 are on the state’s failing list, and almost half of residents 25 and older did not graduate high school.

Despite the neighborhood’s need for better schools and the public demand for alternatives, the Texas Board of Education this year turned down 17 applications for new charter schools throughout the state. Dani’s was one of four approved — and the only one in San Antonio to get the green light.

When she first visited the 78207, the 28-year-old Dani says, she was shocked to see poverty that looked a lot like the countries she grew up in, Nigeria and India.

“A poverty I believed didn’t exist in the United States,” she says.

Dani’s family lived in Lagos, Nigeria, until she was 13, when they moved to Bangalore, India. She went to international schools — top-notch programs featuring International Baccalaureate classes and other high-level programming, such as the Cambridge International Examinations, that remains the same from country to country.

In Lagos, Dani was one of 20 students who came from some 15 countries. She learned to love both math and the perspective-altering experience of getting to know other cultures.

It made sense, then, that Dani became a math teacher for THINK Global School, a traveling high school that exposes students to four countries a year. She went on to teach in several U.S. cities, including New York and Pittsburgh, eventually following her medical-resident husband to San Antonio.

Dani was learning about the city’s education scene when she heard she had been selected for a Building Excellent Schools fellowship. The Boston-based program would give her intensive, year-long training to open a public charter school, which she decided should be located in the 78207.

“This is such a tight-knit community of families who want the best for their children,” she says. “What I see in a lot of the families on the West Side is what I saw in my own family.”

The community is rich with art and history. But in contrast to her global background, many of the parents and children she met had never traveled outside their neighborhood, much less to other cities.

“This zip code is their world,” she says. “I believe that if our children in this community never get to see the world outside of their community, they never get to see what it is that they can become.”

Dani says Promesa — Spanish for “promise” — is her commitment to trying to change that. To that end, when the school opens in fall 2019, it will feature global studies, among other things.

Doubling the number of students at top colleges

Dani isn’t the only San Antonio transplant who was astonished to learn about the 78207. Martinez, who arrived here from Nevada in 2015, grew up in a struggling part of Chicago’s South Side with a father who never made more than $7 an hour. Like Dani, he fell in love with the neighborhood’s vibrant culture even as he struggled to comprehend the depth of its poverty.

After taking the measure of the district’s challenges, Martinez set a two-pronged strategy into motion. Borrowing the better charter schools’ strengths, he created magnet schools and other innovative schools with attractive academic themes like Montessori and dual language programs. And he reached out to local and national charter school operators and teacher-training programs and asked them to help run some of the district’s most challenged schools.

At the same time, he launched a radical socioeconomic integration plan to end the isolation and low expectations imposed on his district’s poorest students for generations by reserving seats for them in the sought-after new schools. He identified poverty rates on every block in the district and used that information to create a system for enrolling students equitably.

The combination of strategies garnered some quick successes, drawing national attention. District leaders from around the country in February descended on San Antonio to hear from Martinez and his team and to tour their schools.

The CEO of the network of state and district superintendents Chiefs for Change, Mike Magee, says leaders and policymakers are watching intently as Martinez puts his strategy into action. Of particular interest, he says, is “Pedro’s approach to school improvement and the way he’s partnering with charter schools and charter school networks.”

Last spring, as Dani’s charter school application was in the final stages of an uncertain approval process, San Antonio ISD’s board approved Martinez’s proposal to ask Democracy Prep, a New York-based charter school network, to take over a chronically poor-performing district elementary school that was otherwise facing closure.

Seemingly overnight, the same kind of political battles that have attended the arrival of high-performing, typically non-unionized charter schools in other communities commenced — at full boil.

Like many places, San Antonio didn’t have many of the independently run public schools for years after Texas’s first charter school law was passed in 1995. Those that did open up in the early years tended to be mom-and-pop startups or programs intended for dropouts and other small groups of students. Some were good, some were not, and neighboring traditional school districts for the most part took little notice.

In 2009, a woman named Victoria Rico visited one of what were then KIPP San Antonio’s two public charter schools. A lawyer and the product of a family with a legacy in the city’s philanthropic community, Rico had been appointed to the board of the George W. Brackenridge Foundation, whose sole area of giving was K-12 education.

Like many schools affiliated with other charter management organizations — nonprofit networks with three or more schools — KIPP schools frequently outperform their traditional district counterparts. Last year, Stanford University’s CREDO researchers found that networks like KIPP do particularly well with black and Latino students living in poverty.

Rico was blown away by what she saw at the school and began visiting other charter schools that were successfully replicating — opening new campuses where students were enjoying high academic growth.

In December 2011, Rico invited leaders of the charitable network Philanthropy Roundtable and several high-performing charter school networks to two meetings in San Antonio. The city’s private and family foundations could make a greater collective impact if they joined forces to help underwrite new charter schools, she told them. Meanwhile, the school networks could collaborate to achieve economies of scale.

The outgrowth of those meetings, Choose to Succeed, courted not just charter networks that served impoverished students but also groups that appealed to middle-class families. Bare-bones state funding for all schools, including many in wealthy communities, had sparked dissatisfaction among affluent parents, which translated to demand for schools affiliated with Arizona’s BASIS Schools, regularly named among the best high schools in America, and Great Hearts Academies.

“As much as we want to serve students who have been underserved by [traditional districts], we want to make sure that middle-class families have options,” says Haass. “It’s got to be an ecosystem of different choices.”

In his 2016 book The Founders, which was published by The 74, Richard Whitmire wrote about Rico’s plan, observing that as of 2015, the new schools had attracted a remarkably socioeconomically diverse array of families. A third of families at the first two BASIS schools were white, he reported, and another third Latino. Half of students at Great Hearts’ downtown Monte Vista campus are Latino, and a fourth are low-income.

“It was clear the one action that could truly shut down the charter expansion — creating successful traditional schools for low-income Latinos at scale — was not in the offing anytime soon,” Whitmire wrote, while taking note of an incipient “attitude reversal” at San Antonio ISD, which had a new superintendent.

Under state law, the district had long had the ability to create or oversee charter schools, something it had done numerous times. Opened in 2008, for example, Young Women’s Leadership Academy, an all-girls high school with an admissions test, repeatedly has been cited for high student achievement by both the state Department of Education and U.S. News & World Report’s Best High Schools rankings.

The new superintendent, Martinez, began asking teachers if they wanted to open more in-district charter schools where a certain number of seats would be open to the same affluent families living outside San Antonio ISD who were flocking to charters. The rest of the student body would come from in-district students living in different levels of poverty, to make sure that San Antonio ISD’s poorest families had the same access as those who were on the threshold of the middle class.

“When we first started looking at our new models, our first goal was to redefine excellence,” Martinez says. “We created new [school] models and had a clear focus on excellence. I went and found the best principals I could find, the best teachers.”

The first, a gifted and talented school that didn’t screen kids academically and was open to anyone, acquired a buzz on the parent grapevine overnight. Advanced Learning Academy was followed quickly by a Montessori school, dual-language immersion schools, two schools managed by the Relay Graduate School of Education — a teacher-training program founded by veterans of the high-performing Uncommon Schools and KIPP charter school networks — and numerous other magnet programs and in-district charter schools.

Suddenly, several San Antonio ISD schools had as many applications as the most popular charter schools. The influx of students from neighboring districts began to counter the loss of families enrolling their children in schools outside the district.

“We now have waiting lists,” says Martinez. “This is the first time our district in San Antonio is considered a [district] that has great choices for families.”

Martinez also approached a small San Antonio charter network that operates schools for youth in residential settings, including treatment and detention centers. He asked the John H. Wood Charter Schools to take over the district’s moribund facility for its high school students with the most challenging disabilities and behavior issues, and invited the Dallas-based Texans Can Academies to open a program inside a high school for students who have dropped out or are far behind on graduation requirements.

Local philanthropy took notice, particularly of Martinez’s plan to hire college counselors and ask leaders of the lauded KIPP Through College program to train them to use the charter school network’s strategies, which have dramatically increased the number of KIPP graduates enrolling in and graduating from four-year colleges.

“We want to be the district that graduates children from college, not just to get them into college,” he says. “So our goal is to show our staff, this is what it means to prepare our children for the next level. It creates a great conversation about expectations.”

A KIPP counselor spent the 2016-17 school year working in a district high school. Thanks to the experiment, the number of graduates from Jefferson High School accepted into four-year universities doubled, from 26 percent to 53 percent.

In late 2017, Valero Energy, an oil refinery giant that is headquartered in San Antonio, gave the district $8.4 million over five years to hire two college advisers for each high school and one for each of the smaller schools. The staff supplement school counselors, helping to match students — virtually all of them the first in their families to go past high school — with colleges and universities that will support them academically and financially.

The class of 2017 had the district’s highest graduation rate ever, 85 percent. More than 55 percent of those graduates are attending college this year, and the number attending Tier 1 universities doubled to 7 percent. Students are attending Middlebury College in Vermont, Boston College, the University of Michigan, and other highly competitive schools.

“It’s just the beginning of the work,” says Martinez. “But when we’ve already doubled the number of students attending these types of universities and we could be on track to increase that even more this year, with more of them being college-ready, again it just gives me hope and it makes me feel that we’re on the right track.”

Dueling Pedro hashtags

The Texas supermarket chain HEB, whose family owners are deeply involved in K-12 education in the state, meanwhile, played a major role in creating CAST Tech, a high-tech high school located in San Antonio ISD that is open to students throughout Bexar County. At the end of its first year, CAST earned a 2017-18 “distinction” rating from the state based on its superior student performance in relation to similar schools.

Martinez’s decision to invite Relay to run schools — and train new district teachers — is something other districts are watching, says Magee. “The partnership with Relay is groundbreaking for a variety of reasons,” he says. “One is that Pedro told Relay, ‘You are going to be training teachers for our system, and we want to embed your training in our district.’”

The other thing he says education policymakers have noted: Martinez’s willingness to work with the state. To fulfill its requirements under 2015’s federal Every Student Succeeds Act, the state boosted its support for in-district charter schools, which has meant extra funding for San Antonio ISD schools. The district will get extra support, for example, to help the New York-based Democracy Prep turn around a school that had been on the state’s list of the lowest-performing programs, Stewart Elementary.

Buzz and stronger academic outcomes notwithstanding, district enrollment continues to fall. The 2017-18 school year opened with 1,800 fewer students than the year before. And the 2018-19 school year is expected to see enrollment drop by another 800 students, from 50,695 to 49,895.

Martinez attributed the departures to the presence of charter schools within greater San Antonio. But co-opting them, he believes, will better serve students than digging in and trying to vanquish them.

The 2017-18 enrollment losses were a major factor behind a $31 million budget deficit forecast for the current year. When the administration started looking at spending, Martinez said, analysts concluded the district had 255 more teachers than were needed in its 90 schools.

In May, the school board agreed to lay off 31 administrators and 132 teachers. Sixty-nine were probationary teachers who had one-year contracts. The others were laid off on the basis of performance evaluations, sparking protests and angry calls for the board to fire Martinez.

Flyers with the superintendent’s picture and slogans such as #byepedro already had appeared throughout the city, sparked by the board’s decision in March to sign a contract with Democracy Prep to take over Stewart Elementary.

“Public schools in the United States are under attack, and charter schools are merely the latest attempt by private corporations to rebrand the school reform movement and exploit public funding for profit,” Luke Amphlett, a teacher at San Antonio ISD’s Luther Burbank High School and a union activist, wrote in a commentary for the Rivard Report news site. “The idea that we should be working with them is absurd: their goals — and the goals of their advocates — could not be further from our own.”

Under the terms of a relatively new law, Stewart was projected to become one of the first San Antonio ISD schools to trip a requirement that the state either close a school that remained on its lowest-performing “improvement required” list for five consecutive years or take over its district’s board. Districts can forestall those actions for two years by turning over the school in question to a charter network, nonprofit agency, or university to run.

The San Antonio Alliance of Teachers and Support Personnel sued the district, seeking to block the Democracy Prep partnership, demanded an investigation into complaints that the layoffs were based on manipulated evaluations, and warned board members that there would be staunch opposition to re-election bids. (None of the board’s seven members is up for election this year. A court denied the alliance’s request to block Democracy Prep’s arrival but allowed the underlying lawsuit to proceed.)

But here, too, something largely unprecedented happened. Families — including some affluent parents who just a couple of years ago were reluctant to enroll their children in San Antonio ISD schools — showed up to support the superintendent and board members.

They had hashtags of their own: #parentsforpedro and #padresforpedro.

“Now is the time for parents to speak up and let Martinez and the board know that we appreciate the changes that the district has made already,” San Antonio Charter Moms blogger Inga Cotton wrote. “We want the improvements to continue under Martinez’s leadership.”

My life’s dream

It might surprise most people to learn that, reputation as a free-market frontier notwithstanding, Texas is an incredibly hard place to open a charter school. The politics are cutthroat, funding laughable, and scrutiny so intense that applications routinely top 100 pages.

In December 2017, 21 prospective new schools applied for permission to open. In June, after a six-month vetting process that the state’s education commissioner termed “a thrasher,” Dani’s Promesa Academy squeezed through the tiny end of the approval funnel.

“I’ve always believed that to break out of poverty, you need an excellent education,” she says. “For me, to be able to come to a community like this where children and families haven’t had access to education and are struggling to break out of that cycle, and to bring them hope in a new school, that’s my life’s dream.”

Debate was intense right down to the wire. One state Board of Education member, an administrator at a San Antonio-area district adjacent to the 78207, opined that the area was “oversaturated with charter schools.” Another opposed Promesa because Building Excellent Schools, the nonprofit where Dani was a fellow, receives money from the Walton Family Foundation, the nation’s largest philanthropic funder of charter schools.

Because San Antonio ISD will authorize Democracy Prep, Stewart Elementary’s new leaders will not have to navigate the same procedural gantlet. But it’s anyone’s guess whether Martinez’s desire to partner with would-be competitors will provoke enough opposition to spell the end of his much-watched tenure.

Martinez began his career in education in Chicago Public Schools, arguably the epicenter of pushback against school choice. His experience there, he says, suggests that the success of the in-district charter schools opened on his watch — and their long and diverse waiting lists — may help mitigate people’s discomfort with change.

“There is sometimes a little bit of controversy because unlike my colleagues, I’ve been very open to partnering with … universities or charter operators,” he says. “And charter operators sometimes can be very polarizing. Something that I’ve decided is that we’re going to look at whatever works for these children.”

How San Antonio is designing integration efforts to tap into bilingual roots, and empowering families once forced to give up Spanish

The moment a person begins to dream in a second language is often heralded as the moment he or she becomes fluent, when the brain stops translating a thought into a new idiom and instead pulls up a concept and expresses it in either tongue.

Because language and dreams both connect the dreamer to culture, research suggests it’s also the point at which a person becomes comfortable straddling two worlds.