New Tennessee Teacher Apprenticeship Program Hailed as ‘Game Changer’ in Effort to Reduce Classroom Shortages

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Nahil Andujar was working for a health care company and just two courses away from a bachelor’s degree in microbiology when her husband joined the Army — a decision that uprooted the family of five from Puerto Rico and brought them to Clarksville, Tennessee in 2000.

When her husband recently retired after 22 years, Andujar began to rethink her own career path and recalled her years volunteering in her children’s schools. She became an educational assistant in a Spanish dual-immersion program in the Clarksville-Montgomery schools, northwest of Nashville.

“I wasn’t planning to become a teacher, but I noticed how a teacher could transform a student’s life,” she said.

Now she’s part of an effort to transform educator preparation with the nation’s first apprenticeship in teaching approved by the U.S. Department of Labor. A partnership between the school district and Austin-Peay State University, the Teacher Residency Program is a “grow-your-own” model in which districts recruit candidates from within their communities and give them extensive on-the-job experience before they take over their own classrooms. With the nation’s teachers far less racially diverse than the public school students they instruct, many consider the approach an effective way to recruit more Black and Hispanic educators.

Education Secretary Miguel Cardona highlighted grow-your-own programs in a visit to Tennessee State University last week. He was instrumental in getting Labor Secretary Martin Walsh’s support for the apprenticeship, according to Tennessee Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn.

He visited Tennessee State University to learn more about its own partnership with Metro Nashville Public Schools and told local reporters that it’s important to “make sure that teachers aren’t working three jobs to make ends meet.”

With the nation currently fixed on staffing shortages and the persistent challenges of hard-to-fill positions, efforts to strengthen the teacher “pipeline” are popular among policymakers. Over 20 years ago, a major study of a grow-your-own program for paraprofessionals showed that participants were more likely than new teachers to still be teaching after three years. But the model lacks long-term evidence of effectiveness. Experts say the federal government’s support — and potential funding — should help spread the concept.

“Let’s get rid of this idea of a first-year teacher,” Schwinn told The 74 last month when she announced the new Teacher Occupation Apprenticeship.

By the time candidates finish the three-year program, she said they’ll not only have a bachelor’s degree and teacher certification but also experience working under the supervision of a master educator. While the concept isn’t new, funding for such programs has been inconsistent, according to a nationwide survey of programs from New America, a center-left think tank. The American Rescue Plan offers a new source of support for the model, but that too will run out, Schwinn said.

Access to state and federal funding for apprenticeships, however “is a game changer,” Schwinn said. “It is that permanent, recurring source of funding.”

Putting ‘dreams on hold’

The Department of Labor awarded more than $130 million in grants to 15 states last year for apprenticeships to meet workforce needs across multiple industries. Becoming a registered apprenticeship with the labor department — which requires programs to meet specific quality standards — puts Tennessee’s program in position to receive funding that would cover both pay and the cost of education for participants, removing a barrier that often keeps lower-income and non-white candidates from pursuing teaching.

For now, the state is using $20 million in federal relief funds to support 65 grow-your-own programs across the state, including the one in Clarksville-Montgomery, where Scottie Bonecutter is working in a first-grade classroom while earning a degree and certification in special education.

She grew up in Clarksville, graduated from the district in 2006 and was doing the “whole traditional college thing” she said. Just as she began taking core courses to become a teacher, she got pregnant and had her first son.

“I ended up putting my dreams on hold,” she said.

She became an educational assistant in the district in 2018. By the time she applied for the residency program last year, she felt more equipped to take advantage of her mentors’ expertise.

“Now that I’m an adult, I’m not scared to raise my hand and say, ‘I have a struggle with this,’” she said, adding that the supervising teachers “are willing to literally walk us through every single step of every single decision they make. They are willing to explain every single standard that we use in class.”

Sean Impeartice, the district’s chief academic officer, said sending candidates to college without the support to balance work, education and family life responsibilities is “educational malpractice.” He hires staff members to work as “facilitators,” who Bonecutter said, provide “emotional support, if you have a lot going on at home, at school or in any aspect of life.”

‘Improving practice’

But it’s a challenging time to become a teacher. Entering the field during the pandemic has been a “baptism by fire,” said Impeartice.

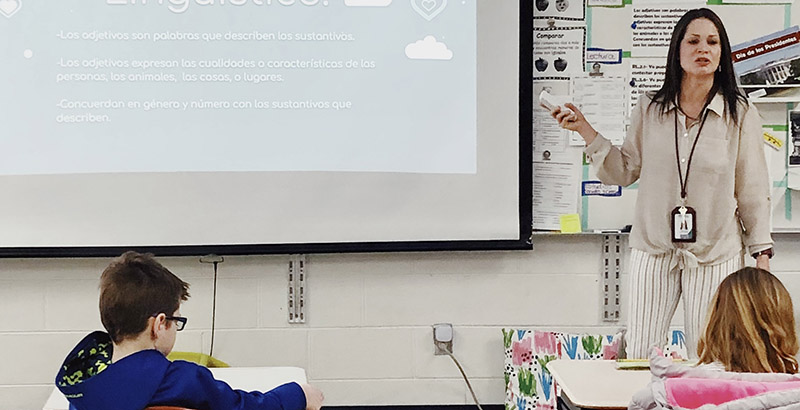

Because of staff shortages, some residents have already led classes on their own. Learning to teach for the first time in a remote arrangement was an additional hurdle. Andujar spent much of her first year in the program teaching Spanish grammar remotely.

“I highly dislike Zoom,” she said. “I’m not a techie person.”

Growing efforts among conservative lawmakers to restrict curriculum also feel out of “touch with the realities of being a teacher,” said Amaya Garcia, the deputy director of New America’s Pre-K to 12 program.

That’s why incentives, such as full tuition and mentoring support, are important for addressing teacher shortages, she said, adding that recruiting paraprofessionals, like Andujar and Bonecutter, is a “logical and sound investment” for policymakers because many already have some college credit, classroom experience and often hail from the communities they’re serving.

Apprenticeships generally receive bipartisan support. Governors of both parties have highlighted the model during state of the state addresses this year.

But researchers don’t know enough about whether participants in grow-your-own programs stay in teaching or improve student learning, Garcia said. In 2001, the Wallace Foundation evaluated its $50 million Pathways to Teaching Careers program for paraprofessionals and other non-certified staff and found that 81 percent of participants remained in teaching for at least three years after completing the program, compared to 71 percent for new teachers in general.

There’s even less data on whether students in high school pathway programs ultimately enter and stay in teaching, even though such programs are growing in popularity.

Just last week, the Chicago Public Schools announced that it wants to expand the number of graduates it hires through its Teach Chicago Tomorrow program from about 140 annually to over 500.

One program that Garcia considers “exemplary” is the two-year Bilingual Teacher Fellow program in the Highline Public Schools, near Seattle — a partnership that began in 2016 with Western Washington University to address a specific need for bilingual teachers.

Sandra Ruiz Kim, formerly a manager in a dental office, was among the first to finish the program in 2018. Now a sixth-grade Spanish teacher at Glacier Middle School, she noticed a difference between those who completed the fellowship and those without such experience.

“We were able — even as first-year teachers — to have meaningful conversations about improving practice,” she said, adding that the experience also gave her access to a network of colleagues, “which can be vital for career progression in an industry that often depends on professional relationships and word-of-mouth reputation.”

A recent Florida study showed that “homegrown” teachers — those who teach in the districts where they graduated — contribute to small improvements in student performance in English language arts.

That confirms why recruiting teachers from the community can be “an impactful strategy,” Garcia said, adding, “We’re going to be getting more proof points because we’re going to have more districts like Highline that have been doing this for several years.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)