New Study Finds Expanding Full-Day Pre-K Boosts Enrollment, Attendance

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Enrollment and attendance in pre-K — especially among Black and Latino preschoolers — improves when programs operate for a full school day instead of a few hours in the morning or afternoon, a new study shows.

Enrollment more than quadrupled among Black children and tripled among Latino students when the Chicago Public Schools expanded full-day pre-K, according to researchers from the Consortium for School Research at the University of Chicago. The findings also focused on an expansion effort in the city’s North Lawndale community.

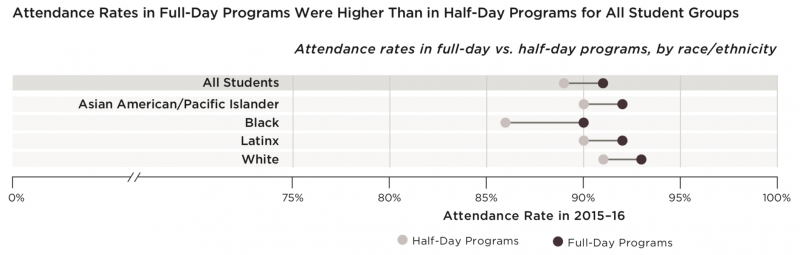

For all racial groups, attendance was higher among children in full-day pre-K, compared with part-day. For Black children, the difference was the largest — 4 to 5 percentage points. Attendance rates also improved among English learners and students from low-income homes.

The results, researchers said, suggest classes operating on a normal school schedule alleviate many of the logistical challenges that might lead low-income and working parents to turn down a free part-day program — like the need to secure child care for the rest of the day, transportation costs and the inability to leave work.

Past research points to more academic benefits for children in full-day programs, compared with part-day. But for policymakers making decisions about how to spend limited funds, “there are trade-offs,” said Elaine Allensworth, a co-author of the report and director of the consortium.

“Full-day preschool requires more resources — personnel and space,” she said, and with full- instead of part-day programs, the “same funding would result in fewer spots available for students to have any preschool.”

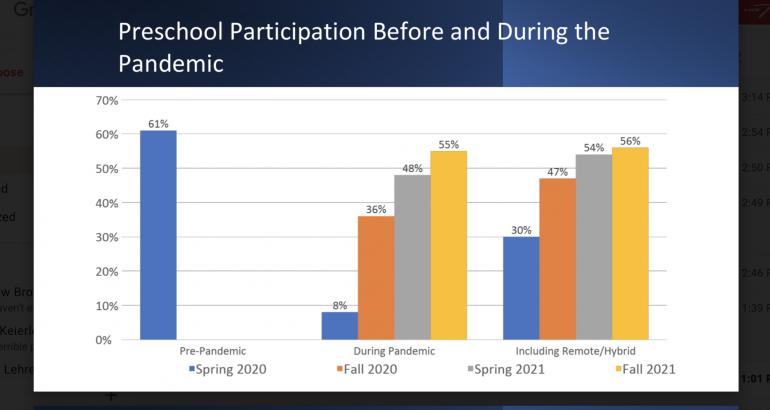

Pre-K programs nationally saw a decline in participation at the start of the 2020-21 school year — a drop from 61 percent of 3- and 4-year-olds before the pandemic to less than half, While there was some rebound last spring, initial counts from fall of 2021 show enrollment has not reached pre-pandemic levels, which experts say could impact future funding for programs. The lack of a vaccine for 5- to 11-year-olds is also one factor influencing parents’ decisions about pre-K this year. Earlier data from the National Institute for Early Education Research’s ongoing survey of parents during the pandemic showed concerns about COVID-19 transmission was the major reason why they decided not to enroll their children.

Allison Friedman-Krauss, an assistant research professor at the institute, said she understands parents’ hesitation.

“A vaccine would certainly make me more comfortable sending my child to preschool, but in reality, I work full time and need child care,” she said. “Plus, the socialization benefits are very important. And the school does take a lot of safety precautions. That said, we all got COVID during Omicron, and I’m pretty certain one of my kids brought it home from school.”

But access to pre-K is still a factor as well. The institute’s annual state preschool yearbook shows that public programs nationally serve about a third of 4-year-olds and only about 6 percent of 3-year-olds.

Looking ahead to next fall, many state leaders and early learning advocates were expecting to see new federal funding for universal pre-K from President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better plan. Instead, they’re waiting on details of a smaller package — one they hope West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin will support. The moderate Democrat blocked the earlier $1.7 trillion package that passed the House, but he’s voiced support for universal pre-K.

“Our crystal ball is not working that well right now,” Steven Barnett, senior co-director of the institute, said about prospects for new federal pre-K funding. As the research center prepares to release its 2021 yearbook in about a month, he said he sees “much increased need.”

According to last year’s report, just New Jersey, North Carolina, Oklahoma, West Virginia and the District of Columbia spend enough to deliver high-quality, full-day preschool. The authors estimated it would take $30 billion to expand access to all 3- and 4-year olds in low-income families and another $32 billion to provide access for all preschoolers.

The Chicago study, the consortium researchers wrote, can inform leaders’ decisions about where to target full-day expansion efforts. Chicago, for example, focused expansion in communities with large Black and Latino student populations, but where pre-K enrollment rates were low. They also prioritized elementary schools with available classroom space. Between 2012-13 and 2015-16, enrollment in full-day pre-K in the city increased from 1,700 children to more than 6,000.

Even without new federal funds, some states have recently launched full-day pre-K expansion efforts. In Maine, 14 school districts will receive $300 million in COVID-19 relief funds for pre-K, enough to serve 500 children. And New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy last fall announced he would spend $17 million to increase enrollment in full-day pre-K in 19 school districts.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)