Aldeman: There Is No ‘Big Quit’ in K-12 Education. But Schools Have Specific Labor Challenges That Need Targeted Solutions

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The full numbers aren’t in yet, but 2021 will likely set a modern record for number of Americans who quit their jobs. Economists have dubbed it the Great Resignation, as millions of employees search for higher pay and better working conditions.

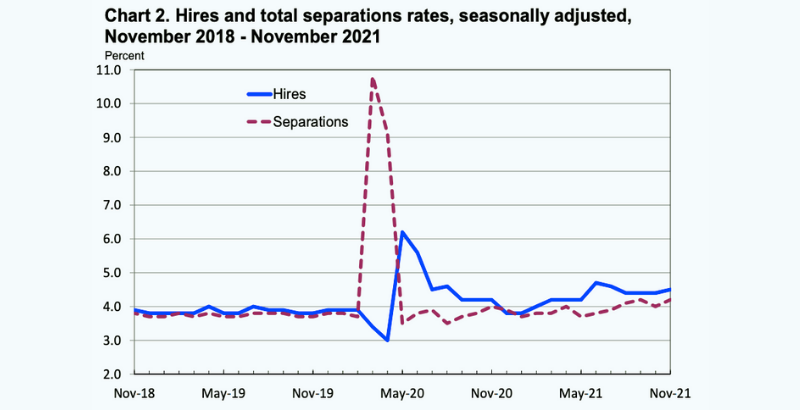

Is this Big Quit happening in education? The data suggest the answer is no. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, while turnover rates are setting new highs in the private sector, they look pretty normal in public education.

That doesn’t mean there are no labor challenges in K-12. It’s just that those issues are smaller in magnitude than what the private sector faces, and they are much more about specific schools and particular roles within schools. Districts should respond accordingly with solutions tailored to the actual challenges schools face.

K-12 districts are reporting a higher number of vacancies compared with historical norms. In a typical year, a school district with 1,000 employees might have about 10 to 15 job openings in January. But this year, the number is on track to be twice as high. Still, a high vacancy rate does not necessarily mean people are quitting at higher rates. Instead, the elevated job openings are caused by a mix of factors, including a desire to staff back up after employment reductions last year, an influx of state and federal money allowing districts to spend freely and a tight labor market fueled by lingering COVID fears and stiff competition from other industries.

Moreover, just because districts have more job openings than normal, that does not mean they’re facing the same labor challenges across the board. When researchers Dan Goldhaber and Trevor Gratz scraped Washington school websites this fall to look at what type of positions school districts were looking to fill, they found that districts had more total job openings for para-educators and athletic coaches than they did for classroom teachers.

Even among educators, some roles are much harder to fill than others. To get a sense of relative scarcity, Goldhaber and Gratz divided the number of job openings by the total number of employees already in those positions. They found that districts were facing disproportionately large challenges in filling special education, English learner and STEM jobs. For example, relative to the number of positions overall, there were eight times as many job openings for special education teachers as general elementary teachers. These disparities were worse in high-poverty and rural districts. It’s tempting to group all these issues together as one labor shortage, but districts can’t respond to these discrete challenges with universal solutions.

On the turnover side, states and districts have not released much real-time data yet. To fill that vacuum, observers have relied on teacher surveys that describe large numbers of educators as stressed out and considering quitting.

But such responses can be misleading. Last year, surveys showed that teachers were dissatisfied and burned out, which led to predictions that they would leave the profession en masse. And yet, statewide reports from Idaho, Massachusetts, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah and Washington eventually found that teacher retention rates rose. Educators may have reported higher stress, but they stuck around anyway.

Turnover rates also vary within schools. For example, data from the Colorado Department of Education in 2020 showed that classroom teachers had the lowest turnover rates among education employees. About 14 percent of teachers left their district, compared with 24 percent of instructional support staff and 28 percent of paraprofessionals. Other studies have found that classroom teachers’ turnover rates look more like those of nurses and accountants than their colleagues within schools.

The fact that teacher turnover is low overall shouldn’t be surprising. In general, government workers have lower turnover rates than employees in the private sector. And across industries, salaried employees with more academic credentials are less likely to leave than hourly workers with fewer credentials. These trends were true before March 2020, they’ve remained consistent during the pandemic and they’re likely to persist going forward.

Discrete challenges should demand targeted compensation solutions. Yet, too often, districts will offer across-the-board salary increases instead of funneling extra pay to those roles with the largest labor gaps. Even as the labor markets vary across position types and schools, the typical salary schedule continues to treat physical education and physics teachers interchangeably. Historically, districts have been less than eager to use compensation as a tool to attract and retain workers in targeted areas, even as research suggests that offering stipends in specific shortage areas can help improve employee retention.

There are signs that may be changing. As my colleague Katherine Silberstein and I write in a new Edunomics Lab report, a number of districts have broken from tradition during the pandemic to pay teachers outside their traditional salary schedules. We found districts pursuing a wide range of innovative compensation ideas, including flat-dollar raises, nonrecurring bonuses and incentives to address longstanding recruitment and retention issues.

While we don’t yet know how pervasive and persistent these new pay models will be, it’s notable that districts are pursuing teacher pay reforms after decades with almost no movement to address the problems with rigid salary schedules. Beyond the pandemic era, these types of approaches could pave the way for savvier, more nimble teacher compensation packages that are more responsive to the staffing challenges schools actually face.

Chad Aldeman is policy director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)