Charter Backers Blast Ed Dept. Proposal That Could Curb Sector’s Growth

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

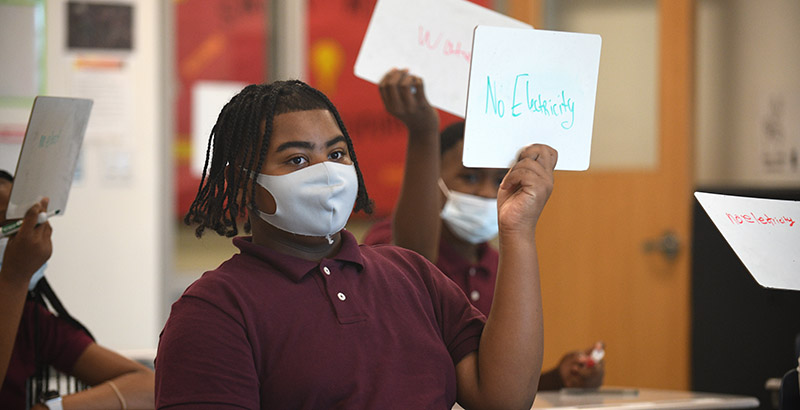

Social Justice School, located in a diverse northeast Washington neighborhood, opened in August 2020. Founder Myron Long’s vision for the charter school is to prepare students for both good jobs and community activism.

But first his staff had to respond to the “pandemic’s aftershocks,” including student learning gaps and parents’ loss of work. Now with 106 students — 99% of them Black and Latino — the school has leaned on a $1 million grant from the federal Charter Schools Program for new technology, curriculum materials and furniture.

Schools like Long’s could have a much harder time getting off the ground if the Biden administration’s plans to revamp the $440 million grant program become final. The U.S. Department of Education’s proposed rule would give preference to charters that districts view as potential partners and discourage new applications in communities with voluntary integration efforts. And if districts are losing enrollment — as they are in D.C. — new charter schools might not be well-received.

“As a Black male who leads a single-site school in Washington D.C., this is extremely concerning,” Long said.

The rule could significantly alter a program that has given a boost to almost 4,100 existing charter schools — roughly 53%, according to the department. Established charter networks like KIPP and Success Academy Charter Schools are among the grantees.

Nina Rees, CEO of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, said the funds help launch new charters, which typically don’t receive state and local funding until they begin admitting students. The program is especially important for “aspiring school leaders of color” who might not have financial backing from a foundation, she said.

With nearly 65% of charters being single-site schools, Rees added, “these proposed regulations are a direct attack on new schools like this.”

Congress has taken note of the backlash. North Carolina Rep. Virginia Foxx, ranking member of the House education committee, said in a statement that the “administration is manufacturing authority it doesn’t have to add unworkable requirements to these charter school grants.” On Monday, the department extended the deadline to comment on the rule from Wednesday to next Monday after six senators asked for more time. In a statement to The 74, the department said the “administration recognizes that there is a place for high-quality public charter schools and supports continuing important investments.”

The debate comes amid a period of change and growth for the charter sector. Last school year, charters saw their largest jump in enrollment in six years — a 7% increase. Initial reports from states such as Alabama and Massachusetts show growth is continuing.

At the same time, Democrats have soured on charters in recent years after a long period in which they enjoyed bipartisan support.

“The Biden administration breaks that tradition,” said James Merriman, CEO of the New York City Charter School Center. “It is clear that they looked around and decided that hewing closely to the wishes of their political patrons in the teachers unions was the way to go. Since they cannot kill us directly, they must resort to attacks on start-up funding.”

Advocates say the department didn’t consult with them before writing the regulation. North Carolina Sen. Richard Burr’s letter noted that the department turned down his staff’s request to meet.

“It doesn’t feel like charter school leaders are a valued part of the process,” said Sonia Park, executive director of the Diverse Charter Schools Coalition, which promotes efforts to create charters that are more racially balanced. As written, the regulations would “make it very challenging for even a diverse charter to get approval if enrollment is declining in a district,” she said.

She pointed to Prospect Schools in Brooklyn, New York, which opened in September 2020, and Atlas Public Schools in St. Louis, which opened last fall. Both designed their schools to reflect the make-up of their communities, but because enrollment is declining in their districts, the schools “would have had extreme difficulty in being approved” today, she said.

The department stressed that U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona spoke last year at the National Charter Schools Conference and has gathered input from charter leaders throughout the pandemic.

One organization the department heard from was The Century Foundation, a progressive think tank that in 2019 issued recommendations for ways the program could promote integration. Halley Potter, a senior fellow at Century and a co-author of the report, said she had a call with the education department before the draft of the rule was issued March 14.

Her report cited federal data showing that charters are more likely than district schools to have student bodies that are more than half Black or Hispanic. In some pockets of the country, however, charter schools are more likely to draw higher-income, white families away from district schools, contributing to racial segregation. Studies have borne this out in North Carolina and Kansas City, Missouri.

Derek Black, a law professor at the University of South Carolina, said in communities with long-standing integration efforts, charters often “operate as an exit strategy for white families who are resistant — consciously or subconsciously — to more diverse environments.”

Potter called the department’s proposal an effort to make sure charter schools “fit in with the context of [their] local community.”

“I really hope that we could see a broad base of charter supporters getting on board with this,” she said.

‘A lifeline’

The Charter Schools Program, begun in 1994 under the Clinton administration, is a competitive grant that provides funding for start-up expenses. Smaller networks have also used funds to add more schools. When Uplift Education, based in Texas, expanded from Dallas to Fort Worth, where it would serve another 2,000 to 3,000 students, the federal grant program supported planning, expanding staff and family engagement efforts, said Rich Harrison, formerly the network’s chief academic officer.

Under the proposed rules, states applying for the funds would have to prove that there is “sufficient demand” for charters, including support from the local community and evidence that district schools have more students than they can serve.

In districts with declining enrollment — a trend across most urban districts nationwide — new charters would face a tougher time getting approved, said Harrison, now CEO of Lighthouse Community Charter Schools in Oakland.

“The anti-charter rhetoric in Oakland is at an all time high,” Harrison said, after the district voted in February to close seven schools.

Community impact

Charter opponents argue that the grant program has been a vehicle for privatizing education and financially benefiting for-profit entities. In a commentary for The Washington Post, Carol Burris, executive director of the Network for Public Education, called the new requirements “sensible rules of the road” and downplayed the rule’s impact.

In a comment to the department, she pointed, for example, to Torchlight Academy, a North Carolina school and grant recipient operated by for-profit Torchlight Academy Schools. The state voted in March to revoke the school’s charter, citing alleged conflicts of interest that benefited the family operating the school. The charter is appealing the state’s decision, saying it has cut ties with the family.

The proposal would require schools receiving the grant funds to pledge that they won’t contract with a for-profit organization to assume most or all of the operation of the school. Grantees would also have to make those agreements public.

Karega Rausch, president and CEO of the National Association of Charter School Authorizers, said he appreciates the focus on transparency. But he and other charter advocates have problems with a requirement that states applying for the funds conduct a “community impact analysis.” Such a process would have to take “into account the student demographics of the schools from which students are, or would be, drawn to attend the charter school.”

Rausch said local authorizers, not state officials, should be responsible for determining whether there is adequate demand for a charter school. He added that the department is sending a mixed message.

“You can’t simultaneously say that it’s a good thing to listen to communities and families and then federally impose specific kinds of schools on communities,” he said.

The education department would give preference to charter applications in which current and former educators are deeply involved in leadership and development of the schools. Another priority for the department is that districts and charter operators work together on issues such as joint teacher training or transportation. At least one district school would have to provide a letter in support of working with the charter.

Rausch said that provision gives the districts leverage, adding that charter demand has increased because they “meet the needs of families” who feel their children aren’t being well-served in traditional schools.

“We are all in favor of collaborative efforts, but it’s got to go both ways,” he said. “We don’t want us versus them. That is old politics.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)