Study: Multi-Year Gates Experiment to Improve Teacher Effectiveness Spent $575 Million, Didn’t Make an Impact

A major, long-term experiment in improving teacher performance funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation failed in its aims, according to a study released today by the RAND Corporation. The intermediate and long-term student outcomes in affected schools were not improved, and new measures of teacher effectiveness devised through the initiative rated almost all teachers highly, the authors found.

The mammoth study, conducted by RAND in conjunction with the American Institutes for Research, renders a final verdict on the multi-year reform effort, known as the Intensive Partnerships for Effective Teaching. An interim report, released two years ago, had given onlookers a preview of the initiative’s results — few of which were trending upward.

The Intensive Partnerships undertaking sprang from a 2006 paper on teacher effectiveness written by education expert Thomas Kane. Researchers have typically found that teacher quality is among the most important factors in student performance, and that proxies such as educational attainment or teacher experience are poor predictors of performance in the classroom.

Influenced by Kane’s research, the Gates team joined with seven partners in a long-term effort to devise measures of teacher effectiveness and create human resources practices to maximize it. Three large school districts were chosen: Pittsburgh Public Schools, Hillsborough County Public Schools in Florida, and Shelby County Public Schools, which merged with the Memphis school district in 2013. Additionally, the foundation selected four California charter management organizations: Alliance College-Ready Public Schools, Aspire Public Schools, Green Dot Public Schools, and Partnership to Uplift Communities Schools.

Between the 2009-10 and 2015-16 school years, the districts and CMOs were awarded roughly $575 million, including $212 million directly from the Gates Foundation. The remaining funds came from a combination of sources, including the districts and CMOs themselves, local philanthropies, and the federal government.

These funds amounted to expenditures of between $868 per pupil at Green Dot to $3,541 in Pittsburgh. Using the money, the schools were meant to develop a measure of teacher effectiveness that accounted for both metrics of student achievement (on standardized tests, for example) and in-classroom observations by administrators.

School leaders were then expected to make use of their teacher effectiveness rubric when making decisions about hiring and recruitment, compensation, placement, tenure (where applicable; the CMOs did not grant tenure then or now), and dismissal. Ultimately, the goal was to expose low-income and minority students to better teachers, improving their rates of high school graduation and college attendance by doing so.

The plan didn’t work, according to the research team.

“By 2014-2015, student achievement, [low-income minority] students’ access to effective teaching, and dropout rates were not dramatically better than they were for similar sites that did not participate in the [Intensive Partnerships] initiative,” they write.

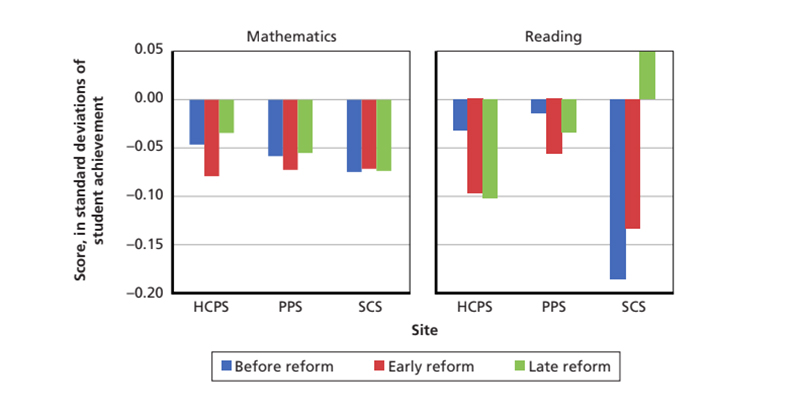

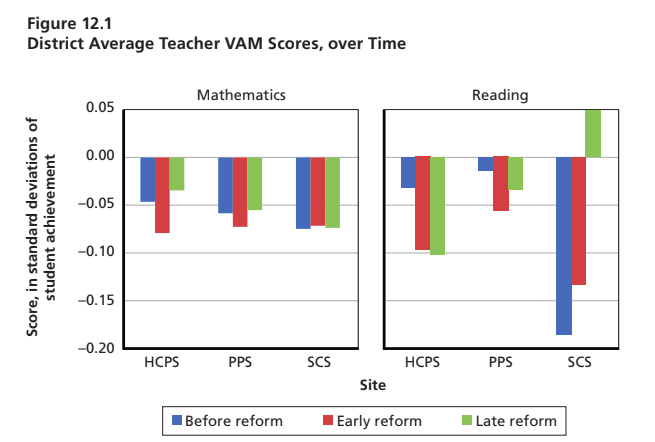

One problem, they find, is that the spiffy new teacher effectiveness ratings were difficult to put into practice. After the 2012-13 school year, no more than 2 percent of teachers in any of the seven school systems were rated in the lowest level of teacher effectiveness. Although the schools rated newly hired teachers more and more effective over the course of the study, RAND’s researchers found their performance to be no better based on their own calculations of value-added modeling (a statistical evaluation of teacher impact on student progress from year to year).

The rating inflation arose partially from the fact that teachers grew resistant to the new evaluations being used for high-stakes decisions like compensation and firing. Indeed, the Pittsburgh Teachers Union kicked up so much of a fuss over the new criteria that the district nearly lost its $40 million grant. Superintendent Linda Lane had to lower the minimum score for effectiveness — twice — before the issue was resolved.

Unexpected contingencies also arose during the six years the experiment was being conducted. Pennsylvania and California experienced school funding crunches, Hillsborough County jettisoned its superintendent (MaryEllen Elia, now the education commissioner in New York state), and virtually every state in the country decided to change their statewide standardized tests.

Whatever the cause, however, teacher performance was not bolstered by the costly study. The authors note that they will continue to track student outcomes for the next two years in case improvements take longer than expected to manifest.

The difficulty involved in revamping teacher evaluations, which can stoke hostility among teachers, bedeviled the Obama administration’s Race to the Top grant program at the same time the Intensive Partnerships initiative was underway. Last year, Bill Gates announced that his foundation would refocus its philanthropic efforts in education away from trying to build a better teacher evaluation and toward funding “networks” of innovative public schools.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)