Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Significant bias has contributed to lower classroom observation scores for thousands of teachers in Tennessee over the last decade, a study published in late December found. Even when controlling for differences in professional qualification and student testing performance, male and African American teachers were rated lower than their female and white colleagues.

The paper is one of the first thorough examinations of classroom observation — the common method of using an evaluator, such as a school principal, to watch and rate a teacher’s work with pupils — across an entire state. Its findings may cast doubt on the efficacy and fairness of the practice not only in Tennessee, but also the huge number of states that also place the in-person reviews at the heart of their federally mandated teacher evaluation systems.

Study co-author Jason Grissom, a professor of public policy at Vanderbilt University, said that distortions in teacher evaluations — which were especially large in observations of male instructors relative to females — held significant sway over decisions on retention, firing, and promotion. Biased scores could undermine states’ ability to raise teacher performance and offer a better education to students, he added.

“If we’re not collecting accurate information, it’s going to disrupt the feedback that’s supposed to be a big way that evaluation can drive improvement,” Grissom said. “And it can treat people unfairly, which can undermine the capacity of the system to improve schools.”

The study, conducted by Grissom and University of Virginia professor Brendan Bartanen, focused on Tennessee as an example of an evaluation framework that has long since reached maturity, with standards-based performance rubrics and observers who are trained to follow specific procedures in rating teachers. One of the original winners of the Obama administration’s Race to the Top school reform initiative, the state first rolled out its system in 2011. In-person appraisals represent the largest single element in each teacher’s overall performance score, alongside student test scores and other factors.

To isolate the possible role of bias in ratings, the researchers accessed detailed administrative data on Tennessee teacher demographics, locations, and work experience. Next, they poured over information from over 460,000 classroom observations between the 2011–12 and 2018–19 school years. Teachers in the state typically undergo between two and five observations each year, and the overwhelming majority are rated on 19 indicators of instruction, environment, and planning. On each metric, subjects are measured on a scale of one (“significantly below expectations”) to five (“significantly above expectations”).

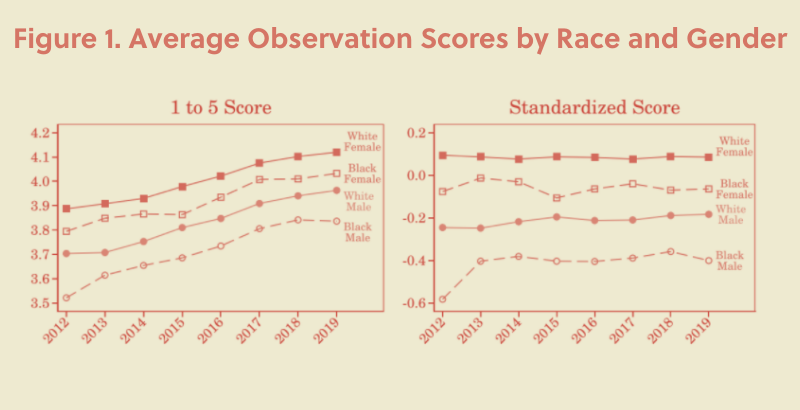

Across all years, male teachers scored approximately .18 points lower than females on average on the 1–5 scale, while African Americans scored approximately .09 points lower than whites. Black male teachers, faced with two possible sources of bias, were the lowest-scoring group, rated about half of a standard deviation lower than their white female counterparts, the highest-scoring. Black women scored slightly higher than white men. While ratings for all groups crept upward over time, gaps between categories remained roughly the same throughout.

The racial and gender disparities shrank somewhat, but did not disappear, when Grissom and Bartanen controlled for factors such as teacher experience, educational attainment (whether or not they had gained a master’s or PhD), and student test performance. In other words, even when comparing similarly credentialed teachers whose pupils achieved at about the same level, white and female teachers were rated higher.

As a way of demonstrating the effects of these gaps, the researchers theoretically “credited” African American and male teachers with the points that they evidently lost due to bias during their classroom observations; ultimately, 9 percent of all male teachers would have ascended to the next threshold on the five-point measurement scale, including one-third of all males rated at Level One and nearly one-quarter of males rated at Level Two.

The difference in those grades, especially at the lower margins of teacher performance, could mean everything to a given educator, Grissom argued.

“The difference between a Level-One and a Level-Two [grade] is very likely the difference between you getting to come back to your school next year or not,” he said. “The difference between Level Two and Level Three might be the difference between you being on probationary or non-probationary status. So the magnitude is large in that sense.”

Exploring possible explanations for the trends, the authors discovered that the racial gap, while smaller, was perhaps more explicable: Black teachers were more likely than white teachers in their own schools to be assigned students who had previously achieved at lower levels and were more likely to be absent from school. They also received modestly higher grades from same-race observers than from white observers, and experienced larger score gaps in schools that employed fewer African American teachers.

The explanation for the difference between genders was murkier, though it could stem from the fact that men are more likely to teach subjects (such as career and technical education) and at grade levels (particularly high school) that tend to see lower classroom observation scores on average.

The results somewhat echo those of earlier research focusing on the Measures of Effective Teaching Project, a teacher evaluation initiative funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. In that study, two groups of teachers were more likely to be graded lower on a set of low-stakes classroom observations: Men, and those who worked in classrooms with higher concentrations of low-performing students and students of color. A 2013 paper authored by researchers at Brown University also found that low-achieving students are disproportionately likely to be assigned to non-white and novice teachers.

Grissom added that his own prior investigations have suggested that school leaders rely heavily on classroom observations as a kind of “eye test” to help form judgments on personnel decisions.

“One of the really stark findings is that principals really emphasize what they’re seeing in observation,” he said. “That’s the real information that’s useful, and in their own minds, they down-weight other information for various reasons.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter