Report: As Tuition Rises, How Private Schools and Microschools Are Working to Increase Access for Low- and Middle-Income Families

More than 5 million students in the U.S. attend 35,000 private K-12 schools, but recent changes to the types of schools that remain open mean there are fewer affordable options for low- and middle-income parents who want a private education for their children.

Many Catholic schools, which historically have sought to educate students from low- and middle-income families, have closed during the same period that private school tuition has been increasing. And though just 10 percent of U.S. K-12 students attend a private school, 40 percent of parents say they’d rather send their children to one, according to a 2018 survey funded by the school choice advocacy group EdChoice.

A new report from Bellwether Education Partners, a research and consulting nonprofit, seeks to offer a fresh look at how private K-12 schools are keeping their costs down, even as the share of students from middle-income families attending private schools has dropped by nearly 50 percent since the 1960s.

“There are a number of private schools that are out there that are trying to serve middle- and low-income students,” said Juliet Squire, a partner at Bellwether and co-author of the report. “That’s not an easy proposition to do without” public funding, she said.

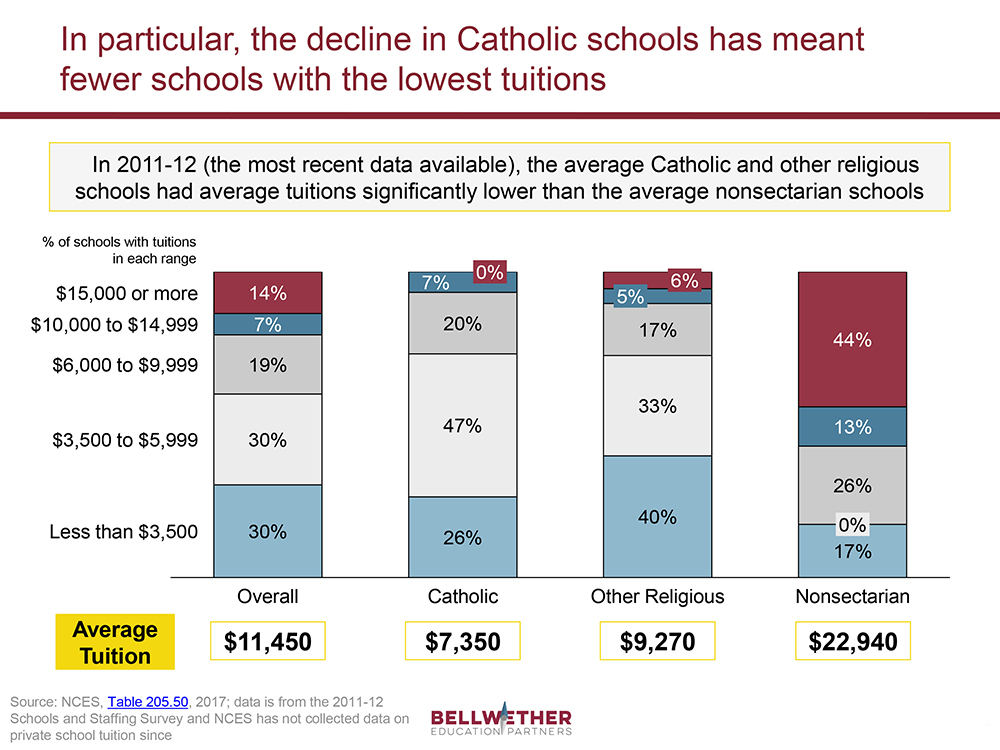

Data on private school tuition are limited. The federal government last published private tuition figures for the 2011-12 school year. Average tuition for Catholic schools, at around $7,400, was less than the overall mean of $11,500 for all private schools and considerably less than the average $23,000 that nonsectarian schools charged.

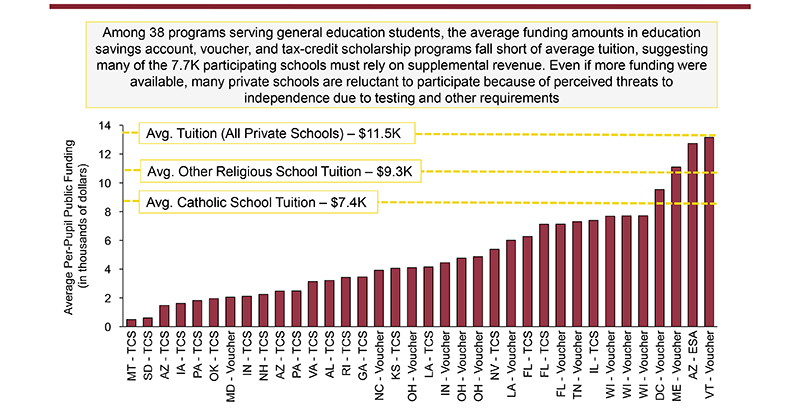

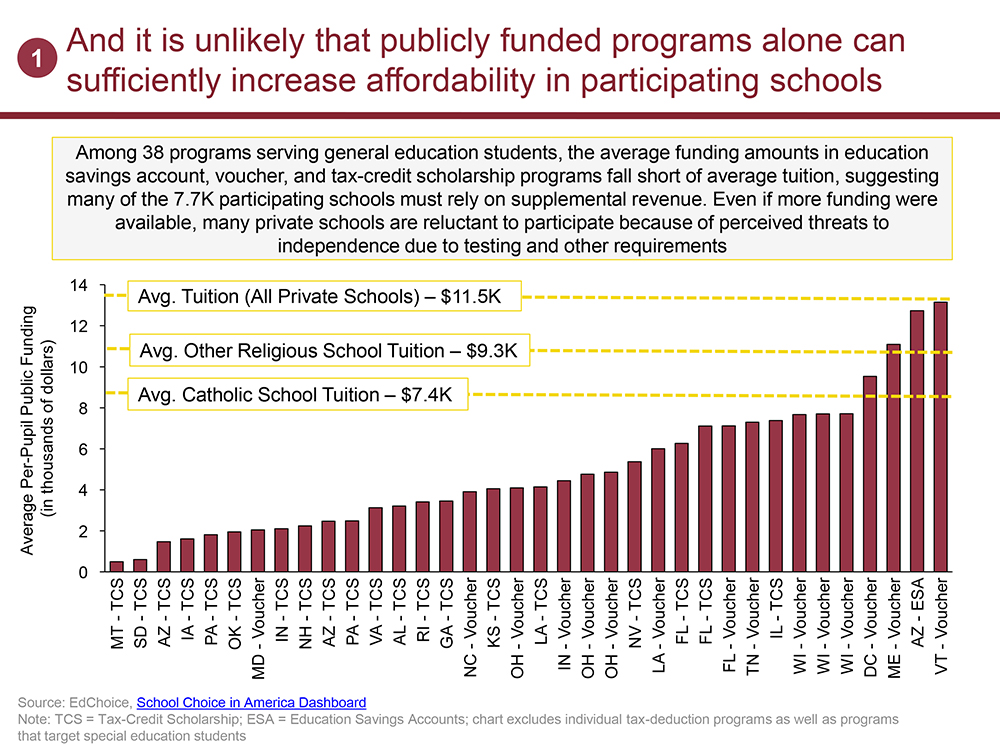

About 500,000 private-school students in 29 states receive public dollars through some combination of vouchers, education savings accounts and tax-credit scholarships. But the public support that students do receive for their private educations isn’t enough to cover full tuition costs except in a few states.

Some private schools that enroll a large number of low-income students rely on a mix of philanthropy, public funds and novel approaches to work-study or cost savings to reduce the tuition burden parents face.

“I don’t think that we come to a full definition of what sustainability is,” Squire said. “What I can say is that these schools that we profile are making it work, and that seems to be admirable in serving middle- and low-income families.”

At Partnership Schools in New York City, which operates seven campuses, parents on average contribute $2,700 even though total expenses per student are close to $10,000. Nearly three-quarters of the students Partnership enrolls are low-income, and virtually all are black or Latinx students, the Bellwether report indicates. The Catholic school group, which Bellwether discloses has been a client, generates two-thirds of its revenue through philanthropy.

Another, the Cristo Rey Network, has students work five full days a month at local businesses to help cover the cost of tuition. According to Bellwether, the corporate work-study revenue generates half of the $14,500 needed to educate each student. Families pay between $1,000 and $2,500 in tuition; the rest comes from philanthropy and public school-choice programs. About two-thirds of Cristo Rey’s 12,000 students across 24 states come from low-income families. It, too, has been a Bellwether client.

The Ron Clark Academy in Atlanta enrolls 150 students in grades 4 through 8; it has a sliding scale for what it charges in tuition, calculated based on both family income and number of children per family. Monthly tuition fees can range from $20 to $50 a month (for families earning less than $35,000) to $1,000 to $1,500 a month (for families with incomes exceeding $170,000). But tuition generates just 4 percent of the school’s revenues. The bulk of its proceeds — 78 percent — comes from a teacher training course it runs. Since 2007, more than 60,000 educators have visited Ron Clark “to observe master teachers, participate in workshops, and observe school culture,” the report says. Training fees range from $525 to $995 and can count as continuing education credits for teachers.

Build Up, founded in 2018, partners with the Birmingham Land Bank Authority to buy blighted homes that students can one day own. Students earn $15 an hour working on renovations while also attending classes, doing schoolwork and earning industry credentials. The contributions families make toward the full $25,000 tuition per student is capped at $1,500 annually. Half of the student’s work wages go toward tuition expenses, while fundraising and tax-credit scholarships cover the rest of the revenues required to keep the school running, the report says. According to Bellwether, “graduates take over the deeds to an owner-occupied home and a rental property” once they enter a four-year college, open their own business or begin earning more than $40,000 a year.

Other schools cut costs by saving on curriculum expenses through iPad purchases and online coursework or by using blended-learning models to reduce the number of lead teachers. But not all schools cited for cost savings can enroll all students. Thales Academy, founded in 2007 by the president of a commercial kitchen ventilation company, does not serve students with disability plans. It presently has eight locations in North Carolina and relies in part on the state’s Opportunity Scholarship of up to $4,200 per student.

Another model Bellwether highlights is the microschool. There are an estimated 200 such academies, mostly private, that have little in common except for their small size. Based on a survey of several dozen microschools, most enroll fewer than 50 students. Forty percent are in storefronts and office buildings. Some have students at different grade levels in the same class.

But few enroll low-income students. Among survey respondents, 60 percent of schools reported having no more than a quarter of students who’d be eligible for free or reduced-price lunch programs. At a similar number of schools, fewer than 25 percent of the attendees are students of color.

That’s not too different from national trends. Across all private schools in the U.S., white students accounted for 67 percent of the student body in 2017. At public schools, white students made up 48 percent of the student population.

“Private school choice is probably not a 100 percent solution for providing high-quality schools to middle- and low-income families,” Squire said. “But they can help, and I think it’s worth studying them for that reason.”

Disclosure: Bellwether Education Partners was co-founded by Andrew Rotherham, who sits on The 74’s board of directors.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)