Rich School, Poor School: As Recession Looms, Test Results Show That Affluent Students Score Higher in Financial Literacy

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

As the U.S. economy hurtles into recession, new test results indicate that a sizable portion of students demonstrate only rudimentary knowledge of personal finance. Large gaps also exist along socioeconomic lines, with students attending predominantly low-income schools falling far behind their peers in more affluent communities.

The financial literacy scores are one component of the Programme for International Student Assessment, a well-known exam that compares adolescents from dozens of education systems around the world. Thousands of adolescents are assessed on the core subjects of reading, mathematics and science every three years, but finance has been included since 2012 as an optional testing domain.

Released earlier this month, scores from the 2018 PISA show American students falling in the middle of the pack internationally, with an average score of 506 out of 1,000 — virtually identical to the average for participating countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the intergovernmental entity that administers PISA. The U.S. ranked behind Estonia, Finland, Canada and Poland, but greatly outperformed non-OECD states like Serbia, Brazil and Indonesia. Scores for American students showed no measurable improvement since the test’s first iteration, in 2012.

At the time of the test’s introduction, the world economy was still recovering from the shock of the Great Recession, which resulted from the bursting of a speculative bubble around real estate investment. Many pinned the blame on the public’s ignorance of economic realities — as evidenced by the elevated consumer demand for high-risk mortgages and financial products — and called for more instruction that would provide young people with the skills needed to make responsible decisions with money.

In the years that followed, fears grew that millennials were entering adulthood on worse economic footing than their parents and grandparents, forced into debt by college loans and taking longer to hit life milestones like marriage and homeownership.

Now financial and labor markets are faltering once again, as fears over the COVID-19 pandemic have forced businesses to close and put tens of millions out of work. Just days after the PISA results were published, new statistics from the Department of Labor showed that the unemployment rate had soared to nearly 15 percent, higher than even the worst months of the Great Recession.

For the 2018 PISA, thousands of American 15-year-olds were assessed on their knowledge of fundamental financial skills and concepts. Test takers were asked to examine sample invoices, chart stock prices over time and identify a fallacious request for personal information from a scam artist purporting to be a bank. Students scoring at Level Five, the highest proficiency level, could apply their knowledge in a range of contexts and account for unfamiliar phenomena like the income tax; those at Level One could make simple decisions, like differentiating between needs and wants, but were much less practiced with more complex financial calculations.

Overall, 12 percent of American students were grouped into Level Five, while 16 percent fell into Level One. As is common in standardized tests like PISA, disparities existed among racial groups: White and Asian American students scored above the U.S. average, while black and Hispanic students scored below.

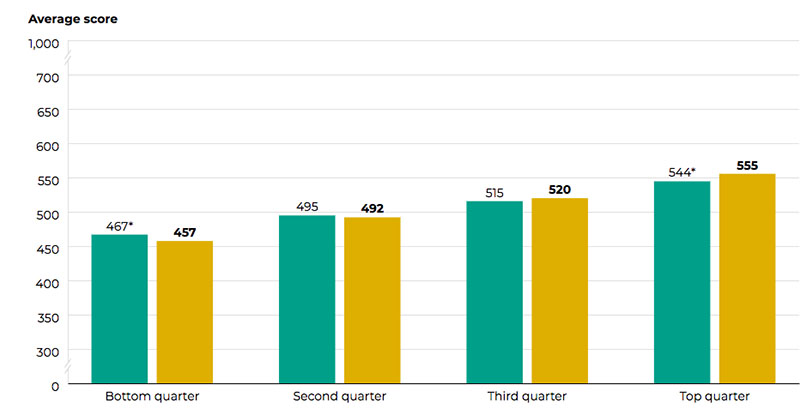

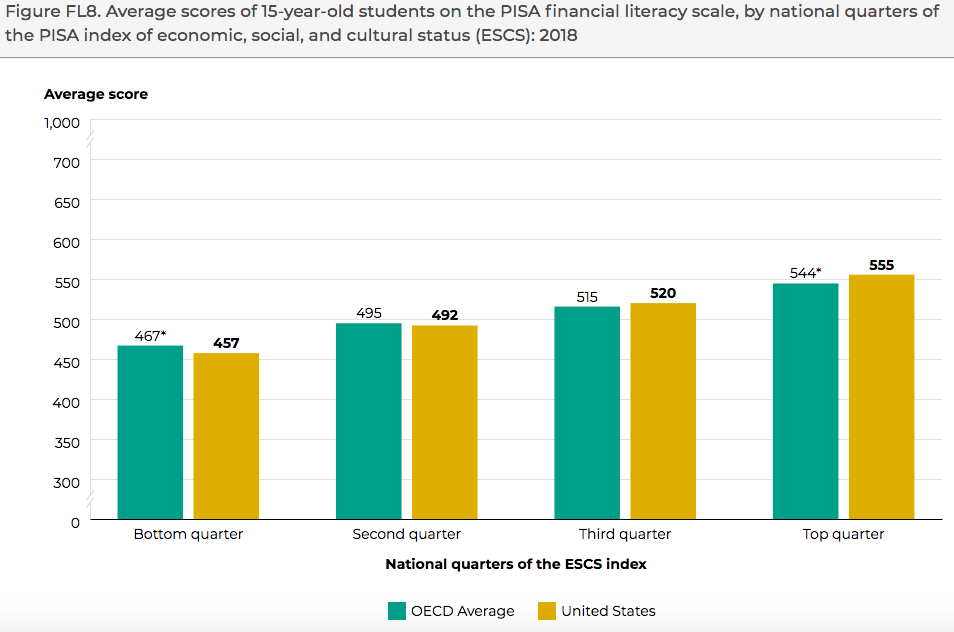

Peggy Carr, associate commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, noted on a media call that class distinctions were even more stark. The average student score in a low-income school (i.e., one in which more than 75 percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch) was nearly 100 points lower than the average in a high-income school (one in which fewer than 25 percent of students qualify).

“Socioeconomic status really does matter,” Carr told reporters.

The results are one reflection of differential exposure to work, money and credit during the K-12 years. Surveys indicate that children from more affluent families are more likely to have access to a credit card — often as a strategy to build their credit from an early age. At a time of long-term decline for youth employment, wealthy kids are also more likely to hold summer jobs.

At the same time, research suggests that education could provide a useful tool. A recently circulated meta-analysis of 76 randomized studies found that financial literacy instruction improved financial knowledge and behaviors for participants in 33 countries. Young people, including students under the age of 14, were shown to benefit in areas like saving and budgeting, and high school finance education yielded a range of later-life advantages.

“High school personal finance graduation requirements … show that financial education reduces non-student debt, increases credit scores, reduces default rates, shifts student loan borrowing from high-interest to low-interest methods, increases student loan repayment rates, reduces payday loan borrowing for young adults, and increases bank account ownership for those with only high school education,” the authors wrote.

Carr noted that the overwhelming majority of PISA test takers reported that they received financial information from their families, though nearly half said that they hardly ever spoke with their parents about financial or economic news. Given the evidence around the effectiveness of financial education, she said, that represented “a missed opportunity.”

“These data show that it is possible to better prepare students than we have for their financial futures, [including] students from less affluent backgrounds,” Carr concluded.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)