‘Right Now, All Students are Mobile’: New Pandemic Data Confirms a ‘Massive Event’ Disrupting School Enrollment

The Greenville County Schools in South Carolina was expecting enrollment to increase by about 1,000 students this fall, continuing a recent pattern driven by affordable home prices and accolades for “livability.” But instead of hitting the estimate of 78,000 students, officials are predicting a precipitous drop to about 74,000.

The news is quite different for the John Adams Academy, a charter school with three campuses outside of Sacramento, California — a growing destination for families fleeing the high-priced Bay Area. The school now has 3,300 students, up from 2,400 last school year.

“We know that the world has changed dramatically,” said Dean Forman, the school’s founder. “People are moving. People are changing jobs.”

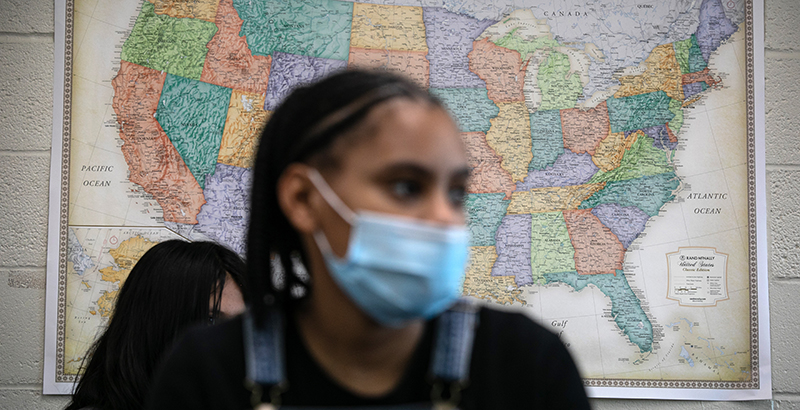

The movement of students in and out of schools — “mobility,” as educators call it — is commonplace. But the school and business closures sparked by the pandemic, and the economy’s subsequent nosedive, are creating a level of disruption some are calling historic.

Past research on the Great Recession showed the economic downturn sparked an increase in student mobility. But the current shift is affecting families across the economic spectrum, from poor students facing evictions and homelessness to wealthier families relocating to exurban “Zoom towns.” In between, many families are opting to send their children to charter schools and so-called learning pods. Others, particularly those with younger children, are engaging in a kind of makeshift homeschooling until their regular schools fully reopen.

“If we would have gone into this year and …seen the mobility we’re seeing without the impetus of COVID-19, all of us would be scrambling, trying to figure out what to do because it would be such a massive event,” said Jillian Balow, Wyoming state superintendent and president of the Council of Chief State School Officers. “It’s like nothing we’ve ever seen before.”

Mobility, however, has consequences — for schools and students. When districts lose students, they also lose state funding tied to attendance. Changing schools can also negatively affect students academically and socially, making it harder for them to keep pace with the curriculum and stay engaged.

District leaders expect a lot of families to return as schools resume in-person learning, leading to additional reshuffling throughout the school year.

“It’s not just the start of the school year where we’re going to face this,” said Stephani Wrabel, a policy researcher at the RAND Corp. “The education system as a whole has never experienced at one time this volume of disruption.”

Many urban districts experiencing enrollment declines this fall, such as Los Angeles and Philadelphia, have been steadily losing students in recent years as charter schools have grown and families have been priced out of urban living. But even districts expecting growth, such as Greenville County, are seeing declines.

In a survey of districts in the Large Countywide and Suburban District Consortium — a group of 18 districts in 11 states — the Gwinnett County Public Schools was originally projected to hit over 181,000 students. Instead, enrollment in Georgia’s largest district is at about 177,400. The Montgomery County Public Schools, a suburban Maryland district just outside of Washington, D.C., has about 162,300 students this fall — over 4,000 less than expected.

“There are real concerns about the implications for future budget years,” said Dan Gordon, senior legal and policy adviser at EducationCounsel, which manages the consortium in partnership with AASA, The School Superintendents Association.

Teacher and parent views

The nation’s school districts won’t know the full extent of the student mobility taking place until 2021. But COVID-19’s historic disruption of school enrollment is supported by two new surveys — one of parents and another of teachers. While the results reveal only snapshots of this moment in time, they provide some striking evidence of how the nation’s student population has shifted during the pandemic.

In one survey, at the request of The 74, researchers at the University of Oregon asked 559 families with school-age children whether they’ve changed schools since the spring for reasons other than moving into middle or high school.

Almost 5 percent said they have a child attending a new school because their family changed residences, and 21 percent responded they have a child in a new school for another reason — offering confirmation of the disruptions many families are experiencing. The questions were added to the researchers’ weekly RAPID-Early Childhood survey measuring the impact of the pandemic on families.

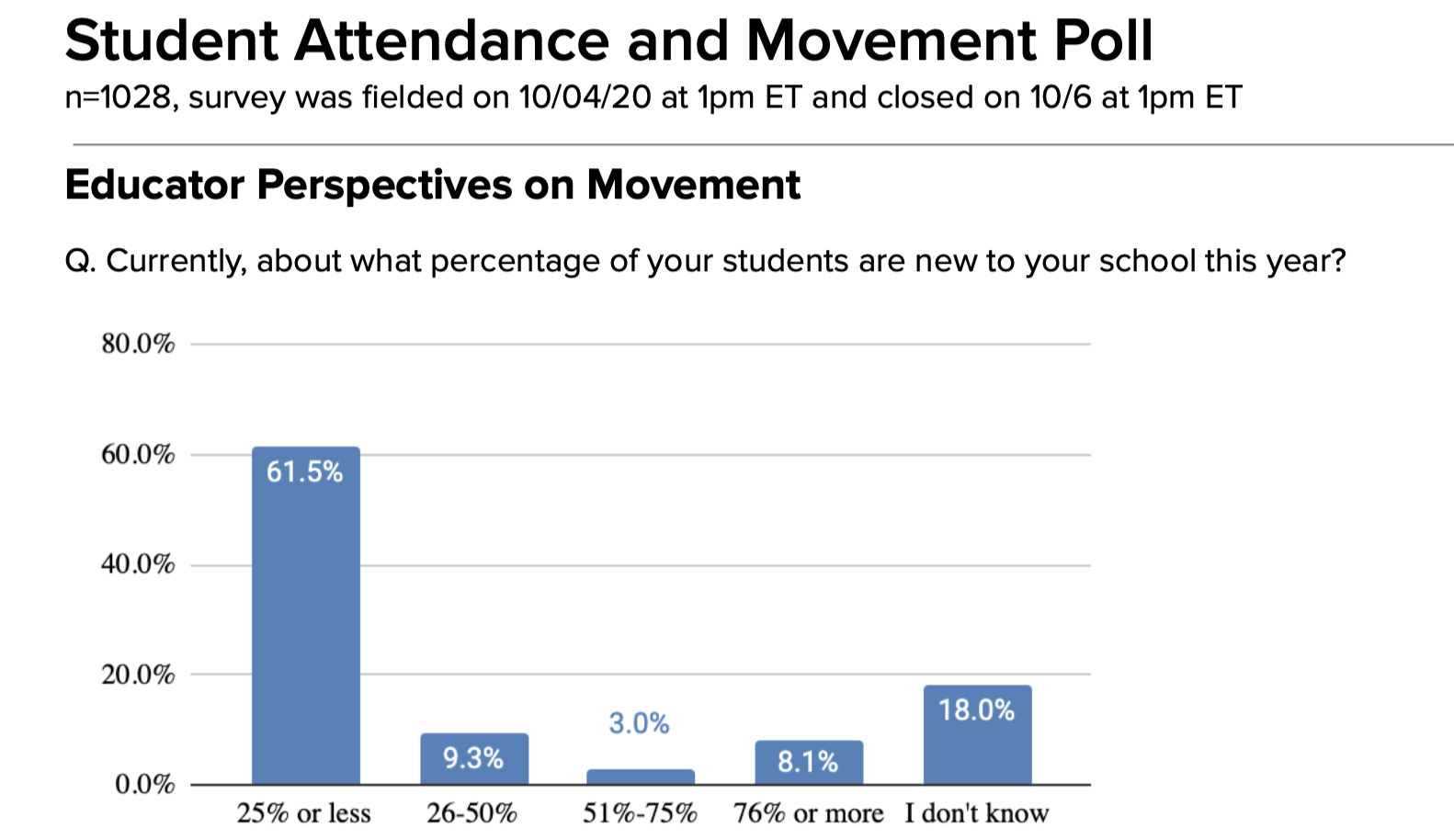

In a separate poll of over 1,000 U.S. teachers conducted by Teachers Pay Teachers, in partnership with The 74, one-fifth responded that at least 25 percent of their students this fall are new. There were key differences by grade level. Almost 12 percent of middle and high school teachers said a quarter to half of the students in their classrooms were new to their schools, compared to 8.4 percent of those teaching lower grades. The majority of teachers who use the online marketplace of instructional resources — and responded to the survey — work in traditional public schools.

Michelle Cummings, vice president of content for Teachers Pay Teachers, said the numbers validate what she’s heard from educators about families still making decisions about schools. Normally by October, “the class list would be well solidified, the relationships would be strong, you’d have some kind of routine,” she said.

While one unexpected school change across a student’s K-12 years is unlikely to lead to later academic problems, research shows that multiple school transfers are linked to declines in reading and math performance, higher absenteeism and a host of behavior problems. Studies have also shown that switching to a virtual charter school — which many families have done this year — can drag down test scores. Even without factoring in mobility, researchers already estimate that school closures have caused students to lose as much as a year of learning in reading and math.

“If students aren’t stable and feeling secure in what they are doing, they’re not going to engage, they’re not going to learn,” said Chad d’Entremont, the executive director of the Boston-based Rennie Center for Education Research and Policy, which published a 2011 report on 11 districts in Massachusetts with high student mobility.

‘Lots of tears’

One factor driving the dramatic changes is the degree to which schools offer remote or in-person instruction.

“We’ve got a bunch of kids I’ve never seen, and they go to school here,” said Jason Mix, principal of Howard Lake-Waverly-Winsted High School, west of Minneapolis. He speculates that one of the reasons his district picked up students is because teachers use live instruction every day. And where he lives, about 20 minutes away, there’s been an influx of families from the Twin Cities. “You can’t keep a house on the market,” he said.

With a new hybrid model in place, the Academy for Advanced and Creative Learning, a charter school in Colorado Springs, Colorado, has picked up new students at every level, but has also seen others go.

“A few families decided that full, in-person learning would work best for their individual situations and chose to withdraw to attend other local schools,” said Teresa Brown, the dean of student support at the school. “We understood that the hybrid model and virtual learning presented a unique challenge for all families, including our own teachers.”

Some parents had such a rough time when schools went remote last year that they pursued other options this fall. Karen DeVault’s four children were enrolled in the Poway Unified School District near San Diego — a district they had attended for three years. But with computers crashing, assorted lockouts from online platforms, and “lots of tears with the kids,” she said she was “not interested in doing a replay of the spring.”

Instead, she enrolled her children in a homeschool program connected with The Classical Academies, a network of seven charter schools that has long employed a hybrid model with virtual and in-person learning. The school assigned the family a head teacher to work with all four students, three of whom have special needs.

Launched in 1999, Classical has seen a 26 percent increase in enrollment since spring, from 4,700 students in June to 5,900 students this fall. Another 1,000 are on the waiting list.

But for many families, the disruption goes deeper than a choice between in-person and online learning. Twenty-six percent of households with children under 18 had problems paying rent or mortgage during July, according to one poll, and a large survey released in June showed many low-to-moderate income households were behind in mortgage and rent payments, especially Hispanic families.

Populations that have been “hit the hardest by COVID-19” are likely to experience the most mobility, said d’Entremont, with the Rennie Center.

‘A long-term issue’

Some districts — including Broward County in Florida, Baltimore County in Maryland, and 12 districts in Oregon’s Umatilla and Morrow counties — have put a moratorium on requests from families to change schools. The goal has been to maintain some continuity for students. In Oregon, it’s also about limiting competition for students if one district opens for in-person learning before the others.

But such changes can make it difficult for officials who track student homelessness to know which families need services, said Barbara Duffield, executive director of SchoolHouse Connection, a nonprofit. Normally, districts provide transportation for homeless students to their original school, but without those requests, schools have lost a key method for identifying students in unstable living arrangements.

“It’s a twin issue of identifying newly homeless students and staying in touch with the ones who were,” Duffield said.

Instead of arranging transportation, Rebeka Beach, an adolescent homeless liaison in the Cincinnati Public Schools, now focuses on ensuring students have devices and reliable internet.

“I often fear that we are missing students because we aren’t seeing them as regularly,” she said.

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, which Congress passed in March, included a ban on evictions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention then extended it through Dec. 31. But those bans haven’t stopped families living in motels from being removed, Duffield said. She added that some homeless liaisons have found families in motels with children who weren’t enrolled in any school.

“If we don’t know where kids are, we cannot serve them,” said Abby Cohen, the associate director for policy and research at the Data Quality Campaign. “This is going to be a widespread issue and a long-term issue.”

Duffield said many districts have asked families to choose between hybrid or distance learning for the entire school year. A superintendent in Florida, for example, has said because “consistency in each class is imperative,” the district will no longer allow movement between in-person and virtual options except for serious health reasons. For families living in shelters or other temporary arrangements, however, there’s a “fluidity in people’s lives that makes it hard” to commit to one plan, Duffield said.

‘A minimum of two transitions’

All students experience transitions when they enter a new grade level or advance to middle or high school, and it can take time to learn routines, make friends, and understand teachers’ expectations. An advantage that teachers had when schools closed in the spring, Cohen said, is that they had seven months to build relationships with students. But establishing a rapport at the beginning of the school year — especially with newly enrolled students — is an extra challenge when school is online.

“For students and the counselors, there is that barrier there” with the screen, said Noelle Carson, who provides online therapy for students attending virtual schools in Indiana.

She added that for students who have changed schools during closures — and are still remote — their eventual return to the classroom might increase anxiety. “Over time, when you don’t have that interaction with students face-to-face, those [social] skills decrease.”

Virtual lunchtimes, Zoom breakout rooms, and welcome bags they send to students’ homes are among the ways teachers say they’re trying to foster some classroom relationships.

One way to think about this year’s students is that “right now, all students are mobile,” d’Entremont said. “They’ve had a minimum of two transitions” since March, and services often targeted toward highly mobile groups, such as tutoring and mentoring, could benefit all students.

In eastern Washington, near the border with Idaho, schools in the Freeman School District are open once a week for K-2 students and more days will be added throughout October. But the district also had in-person “meet-and-greets” for every student in the district so families could visit the campus, talk one-on-one with teachers, and check out devices if needed.

“It took us four days to get through all the kids,” said Superintendent Randy Russell.

Enrollment is down about 7 percent this fall, and the majority of families that have withdrawn are in the elementary grades. But they tell him, “As soon as you return full-time, we’ll be back.”

Disclosure: Linda Jacobson and Stephani Wrabel co-authored “Welcoming Practices: Creating Schools that Support Students and Families in Transition,” a 2017 book about transition and student mobility.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)