‘No One Taught Us How to Do This’: As Families Face Evictions & Closed Classrooms, Data Shows ‘Dramatic’ Spike in Mid-Year School Moves

This article is one in a series spotlighting the broader consequences of families disenrolling their children, students changing schools and children going missing amid the coronavirus crisis. See all our coverage at ‘COVID’s Missing Students.’ (If you or a student you know changed schools or stopped going to class altogether because of the pandemic, tell us your story. On Twitter: #WhereAreTheKids and #IAmHere)

When kindergarten teacher Tabitha Brown received her class list for this fall, there were 27 names on it. But then her school, Global Village Academy, a charter north of Denver, announced it would start the year virtually. The list dropped to 18.

Six weeks later, enrollment inched upward as the school reopened, only to fall again in a month when it closed due to rising COVID-19 cases. Brown’s class is just one example of the disruption affecting classrooms as students fall off the radar.

“I think I know how many students I have, but with all the change, I have to look it up to be certain,” Brown said, adding that the shifting population affects everything she does, from organizing reading groups to helping families navigate online platforms. “I spend more time communicating with families who have missed a piece of information than I do planning what I will be teaching.”

Movement of students during the school year is commonplace, especially in higher-poverty communities. But “the fluctuations we’re seeing now are far more dramatic,” said Michelle Cummings, vice president of content at Teachers Pay Teachers, an online marketplace for curriculum resources, and a former chief academic officer in Oregon’s Medford School District. Whether families are seeking in-person instruction or larger apartments to accommodate learning from home, or are facing eviction on top of remote learning, the pandemic continues to place new academic obstacles in parents’ paths. With schools closing again amid the latest COVID surge, experts say teachers remain stuck in crisis mode and students are struggling to make sense of months of missed material.

“Educators create community, and this disruption tears at the fabric of that community,” Cummings said. “It’s December, and the state of teaching is still a chaotic one.”

Even districts that experienced a sharp decline in enrollment this fall continue to see movement across their schools. By the end of November, 5,500 students had entered schools in the 90,000-student Fulton County district near Atlanta and 3,000 had withdrawn. For a student, even within-district movement at this point in the year still means “a new teacher, a new routine,” said Cliff Jones, the district’s chief academic officer. “That’s going to be tough for a kid.”

Since school started this fall, more Fulton families are opting for in-person learning. But the district still closes individual schools occasionally if too many teachers or substitutes are in quarantine. “We don’t have enough adults to open the buildings,” Jones said.

New survey data — collected by Teachers Pay Teachers, in partnership with The 74 — provides a glimpse into the ongoing interruptions that teachers and families have experienced this semester.

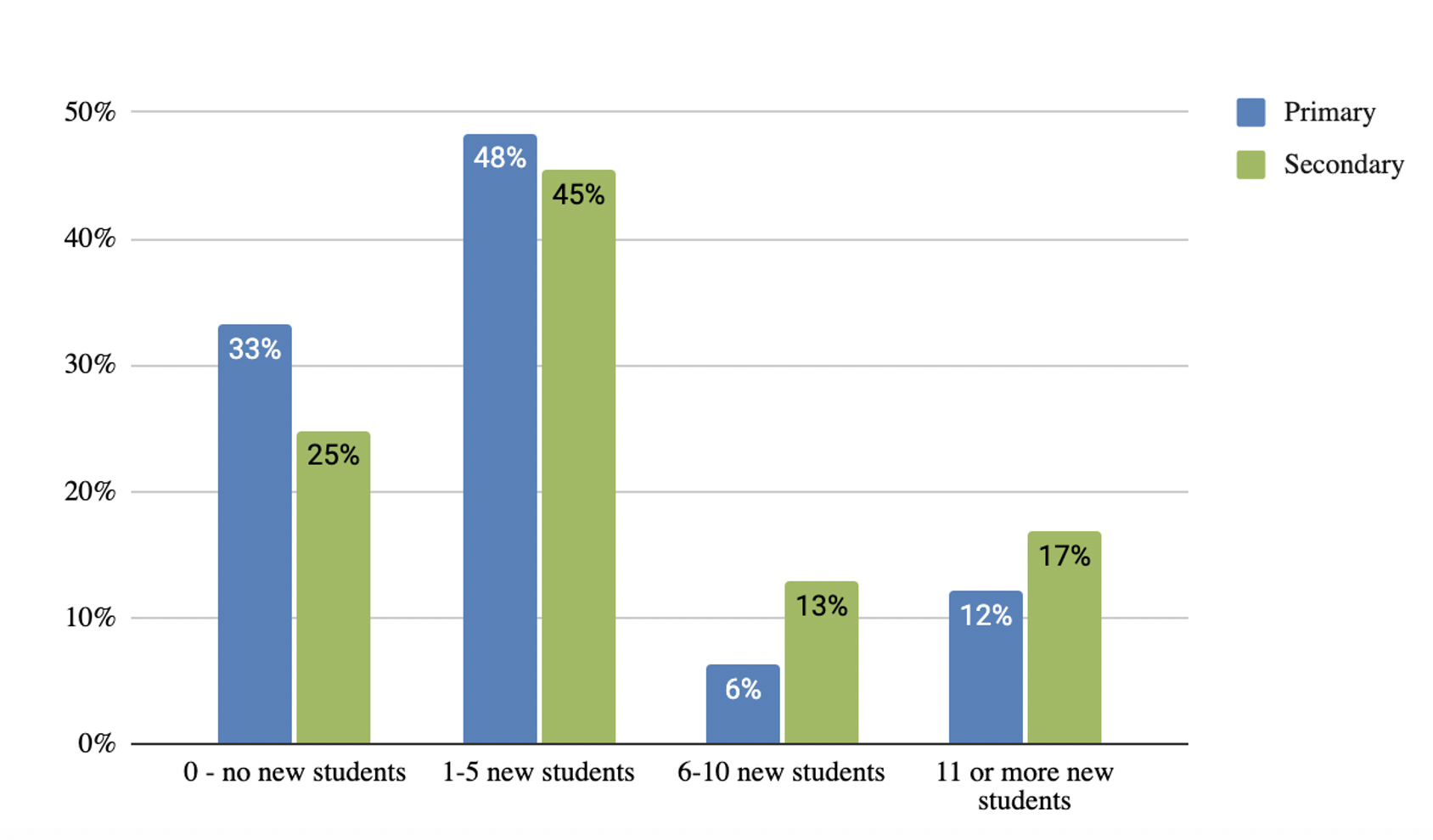

Seventy percent of teachers, out of a sample of over 1,800, have had new students enter their classrooms in the past two months. Fourteen percent said 11 or more new students — close to half of the class for teachers in some schools — had joined them.

“This whole time feels weird because everyone is trying to figure out what works best,” said Elaine Allensworth, director of the Consortium on Chicago School Research. While frequent school changes — or mobility — has been found to harm students, she said families may feel they’re taking less of a risk at a time when most schools aren’t providing in-person programs. “It’s possible people are trying things out they wouldn’t have tried before.”

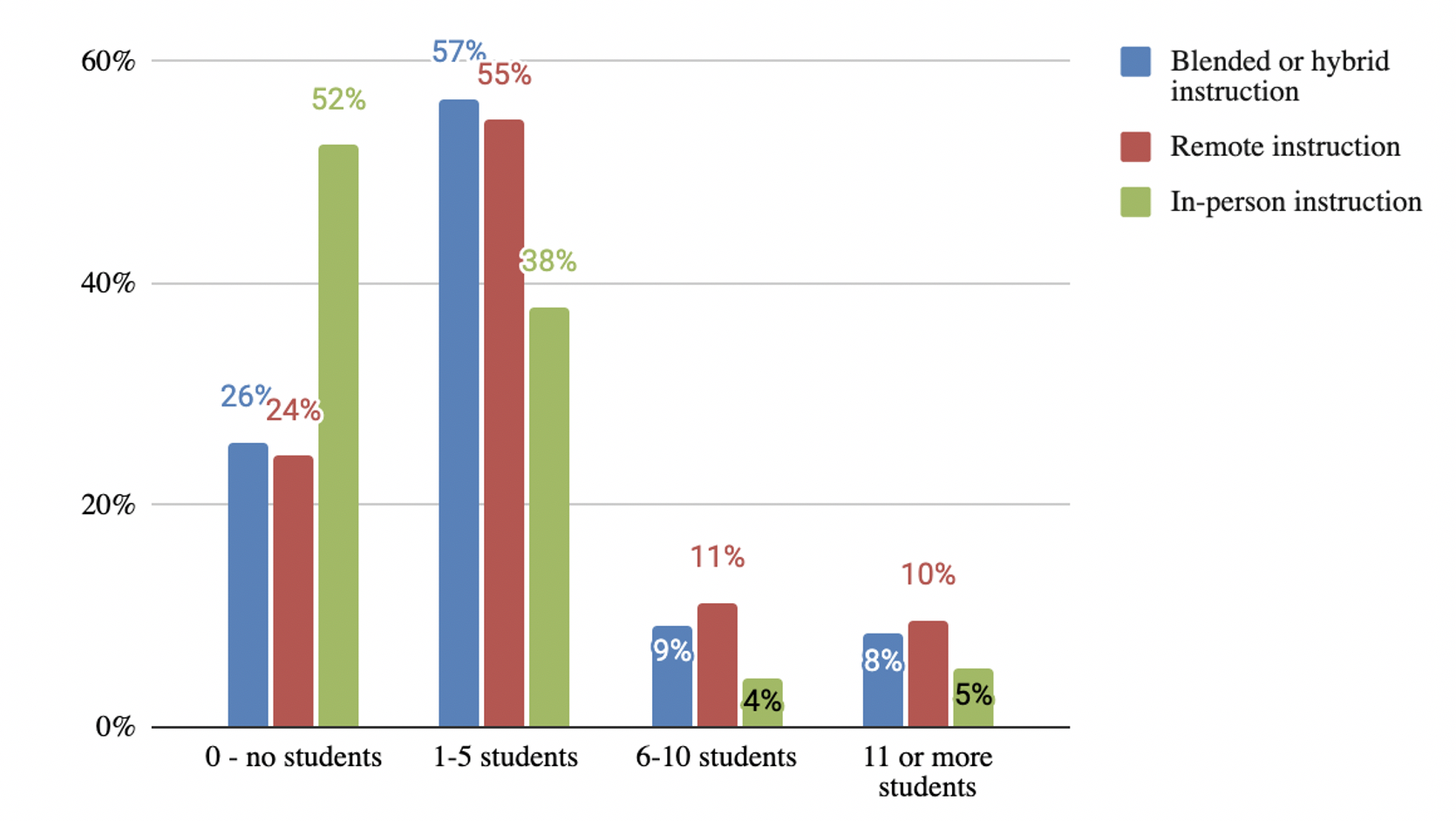

When families choose among face-to-face, hybrid, or remote instruction, that often involves a new class and a new teacher.

Forty percent of teachers in the survey said they’ve had students leave their classrooms in the past two months. And 7 percent said they weren’t sure if they’ve had students leave.

That uncertainty could stem from the fact that some students still haven’t shown up. More than half the teachers said one to five of their students are essentially truant, 9 percent said six to 10 students haven’t attended class, and 8 percent put 11 or more students in that category.

Some students are facing housing instability on top of changes to remote or in-person learning. Unless Congress extends it, an eviction moratorium will expire at the end of this month, which could mean more changes when school resumes after holiday break.

Star-C, an Atlanta nonprofit that operates afterschool programs in apartment complexes, is one organization stepping in to prevent struggling families from experiencing more mobility in such a turbulent year. The organization has provided more than $2.5 million in eviction relief grants to keep 1,735 families in their apartments. The program prevents families from having to double up with relatives or move into hotels, said Allie Reeser, who directs one of the afterschool programs.

The relief program, she said, has been “a big factor for families living paycheck to paycheck, because any interruption … could send them into a dire situation that is extremely hard to climb out of.”

‘Virtual does not equal safe’

Schools receive funding based on enrollment. So the unexpected loss of students could mean the elimination of a teacher the following year. But it also works in the opposite direction. Because funding is typically based on the prior year’s population, schools might lack the staff to manage a sudden enrollment jump.

The shifts have “huge ramifications for student learning and for funding equity,” said Mike Magee, CEO of Chiefs for Change, a network of state and local superintendents representing 14,000 schools and 7 million students. One concerning trend, he said, is that in districts that have largely re-opened, Black and Hispanic families are more likely to choose remote learning.

“Virtual does not equal safe. People need to get that out of their minds,” he said. “Children are safer when they are in school, including in the middle of the pandemic.”

Parents of children with special needs have felt a particular sense of desperation as they’ve watched their children fail to engage in virtual learning.

They include Erica Meyrich-Pinciss, who wanted her son to continue attending his diverse Los Angeles school in a neighborhood the family had enjoyed for 10 years. But this fall, the district placed 5-year-old Barrett, who has developmental delays, in a virtual class with students who have more severe disabilities. The lessons, she said,included a lot of YouTube videos with educational songs.

“He can walk, but he doesn’t talk yet,” Meyrich-Pinciss said. “He will get close to typical, but he needs peers.”

Watching virtual school board meetings of the Hermosa Beach City School District, south of the city, she sensed leaders were determined to open schools as soon as they could. The family moved in October, and on Barrett’s second day in the new district, leaders invited him to participate in an in-person school group. He now participates in his Zoom class, interacts with other students at school, and his speech therapist increased his sessions from one to three times a week.

“We didn’t even have to do anything,” his mother said. Knowing that many special education students haven’t received such services, Meyer-Pinciss found herself feeling “guilty, because it was so nice and different.”

Additional data shows that many parents are still weighing their options. At the request of The 74, researchers at the University of Oregon, as part of their weekly RAPID-Early Childhood survey measuring the impact of the pandemic, asked families with school-age children about their plans for the rest of the school year.

Compared to mid-October, the percentage of parents saying their child is in the same school as last spring has fallen from 61 to 54 percent. The percentage of families who changed schools because they moved is about the same — 4.8 percent in October and 4.2 percent now.

But in the latest round, over 18 percent of the 525 respondents said they have decided to homeschool, and almost 15 percent said their child is attending a different school for a reason other than promotion to middle or high school.

Not all families have warm-fuzzy feelings about transferring their children. Delinia Parris recently moved her grandson King-Maliq from L’Etoile du Nord French Immersion School, part of the St. Paul Public Schools in Minnesota, to Friendship Academy of the Arts, a charter school in Minneapolis open for in-person instruction.

Parris wanted King-Maliq to develop the same “lovely French speaking voice” as his older sister, who attended the French school through fifth grade. But Parris struggled to help him learn a second language over Zoom. “It was like being an immigrant in my own country trying to navigate a language I do not speak,” she said.

Then, as in other parts of the country, COVID cases began to spike and the charter school returned to remote learning. King-Maliq now has roughly five hours a day of virtual instruction, and Parris said getting him to participate is tough. “The reason I transferred him was distance learning, [only] to end up right back in the same situation again,” she said. “I’m at the point where I’m just thinking about … homeschooling.”

“How much learning?’

Even experts who have long studied how school transfers affect students, such as Russell Rumberger at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said switching from online to in-person models — and back — adds “a whole other layer of complexity” to the issue.

The bottom line, Rumberger said, is how much instruction students miss when they transfer. “How much learning is actually going on?”

For Kimberly Dukes’s eight school-age children, the answer this fall was “not much.” Previously, they were enrolled in the Atlanta Public Schools, while Dukes lived with her sister. But when her sister got married, Dukes and her children moved in with her brother in a different neighborhood. When schools re-opened there, she lacked a lease to prove residency.

In October, she enrolled seven of her children in the Georgia Cyber Academy — a free, online charter — while her oldest, Ereunna, went to live with her father in Fulton County so she could finish her senior year in person.

She feels she’s made the right decision for her daughter, who struggled in a “virtual space.” Now, she’s passing all but one class.

But Dukes believes all of her children have lost ground since the spring — in particular her second-grader, whom she now believes reads at a kindergarten level.

“There’s not a hotline I can call and say, ‘My baby, he cannot read,’” she said. “No one has taught us how to do this.”

This article is one in a series spotlighting the broader consequences of families disenrolling their children, students changing schools and children going missing amid the coronavirus crisis. See all our coverage at ‘COVID’s Missing Students.’ (If you or a student you know changed schools or stopped going to class altogether because of the pandemic, tell us your story. On Twitter: #WhereAreTheKids and #IAmHere)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)