‘I Am Beyond Worried’: More HS Students Are Applying for Financial Aid — and Enrolling in College as a Result. Coronavirus May Put an End to Both

When Akyiaha Simpson, a senior at California’s Orange Vista High School, started applying to college last fall, she wasn’t sure how she was going to pay for it. The first step? Filling out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA).

It was a requirement not only to get money for college but also to earn her high school diploma. “My counselor was on me about that,” she said. “I didn’t know what the FAFSA was at first.”

Now, after taking that first step, Simpson is planning to attend Cal Baptist University on a generous scholarship in the fall.

Three years ago, Simpson’s district, Val Verde Unified, became the first in California to make completion of a financial aid application — either the FAFSA or California Dream Act Application — a graduation requirement. In the first year of implementation, the district’s financial aid completion rate rose significantly, from 69 percent to 83 percent. College enrollment rates went up too, from 56 percent in 2017 to 61 percent in 2018.

Val Verde isn’t alone. Across the country, a growing number of districts and states are considering similar mandates due to the strong correlation between completing the FAFSA and starting college immediately after high school.

Traditionally, students don’t fill out financial aid forms for a number of reasons: because they believe they’re ineligible, they find the application confusing, they don’t have support at school or at home or, for undocumented students, they are worried about sharing personal information for fear of deportation. But nationally, students who complete financial aid applications are 82 percent more likely to go straight on to higher education than their peers who don’t finish the forms. That number jumps to 127 percent for students from the lowest-income backgrounds, according to the National College Attainment Network.

In the first year after Louisiana mandated FAFSA completion — the first state to do so — its overall rate topped 77 percent, compared with less than 70 percent nationally. In both 2018 and 2019, Louisiana had the highest FAFSA completion rate in the United States, and a record number of high school seniors went to college immediately after high school in 2018 — almost 1,600 more than the year before.

“Integrating financial aid applications into high school really normalizes the experience of application completion for students so that … it becomes a standard rather than an afterthought,” said Tyler Wu, formerly a senior policy analyst at Education Trust-West.

As Bill DeBaun, the network’s director of data and evaluation, explained it, “We think about FAFSA completion as an early indicator of college-going intention.”

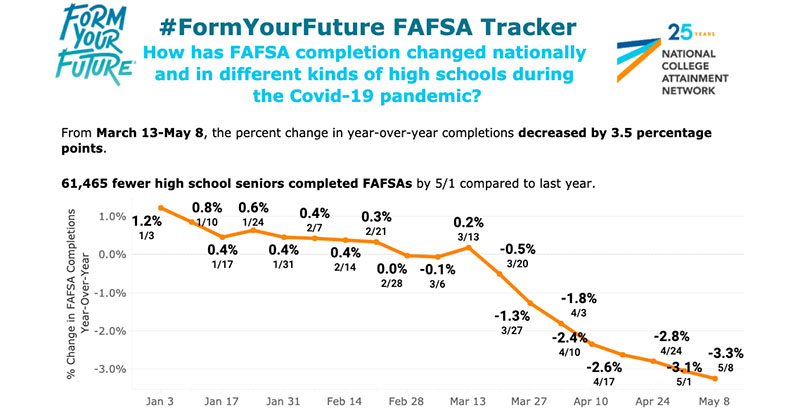

But the coronavirus is undermining those efforts. Since schools nationwide shut down in mid-March, there has been a 3.3 percent decline in FAFSA completion among high school seniors compared with the same time last year.

This means fewer members of the Class of 2020 will likely go to college next fall because of the pandemic. “This isn’t just a numbers game,” said DeBaun. “Every one of those FAFSA completions that doesn’t get done by the end of this cycle represents a student potentially leaving money on the table that would help them finance postsecondary education.”

The same thing is happening among those currently enrolled in college. Compared with last year, some 250,000 fewer low-income college students have renewed their FAFSA, and overall renewals have declined about 5 percent, representing more than 350,000 students. Between March 15 and April 30, nearly 17 percent fewer returning Pell-eligible students filed FAFSA renewals compared with the same time last year. The number was down almost 20 percent among students with incomes of less than $25,000.

‘I am beyond worried’

As of May 8, more than 66,000 fewer high school seniors had completed the application than the year before, leaving approximately $105 million in unallocated Pell Grants unclaimed. In Louisiana, about 2,900 fewer students have completed the FAFSA than last year — a more than 8 percent drop. At a time when students aren’t even sure they’ll be able to finish their senior year classes, Louisiana has waived the FAFSA graduation requirement for the Class of 2020.

“We know how strongly associated FAFSA completion is with immediate postsecondary enrollment after graduation,” DeBaun said. “So where we see declines in FAFSA completion, we would also anticipate seeing plans change for the fall.”

Even students who have completed the FAFSA may not enroll, given the uncertainty about what college will look like in the fall. A recent survey predicted a 20 percent decline in fall enrollment. Another study found that more than half of students were concerned that college enrollment might be delayed due to the coronavirus.

“I am beyond worried that students will give up or think they can just postpone attending a college for a year and not understand that they need to take steps to defer their admissions, or if that is even a possibility at the campus they planned to attend,” said Catalina Cifuentes, executive director of the Office of Education in Riverside County — where Val Verde is located — and chair of the California Student Aid Commission. “We have already heard that preliminary data is showing the number of students who filed their Statement of Intent to Register is lower than years past.”

FAFSA completion rates have dropped even more steeply for students who attend high schools where at least 40 percent of students come from low-income families, and for those in rural areas.

“It’s students at those schools who most often benefit from completing their FAFSA because it opens them up to things like the Pell Grant and other forms of federal and state aid,” DeBaun said.

FAFSA completion rates are down because students lack access to the internet at home to complete the process; because school counselors, who would normally help out, have lost touch with seniors or have trouble reaching them; and because, with the economic downturn, some families now need their children to contribute to the household income.

“Many of our students … need to work to help their families catch up on bills and assist their parents with providing basic needs, so not enrolling into a college for a year is their only option,” Cifuentes said. “The college process is already stressful for first-generation college students, and what they are experiencing now only continues to add to their list of fears and reasons not to attend. As school leaders, we are attempting to balance supporting their basic and emotional needs while trying to inspire them so they don’t give up on the college dream they have worked so hard to achieve.”

Low-income students most affected

The decline in FAFSA completion is most likely hitting these students harder than their higher-income peers. Community colleges have later deadlines, and research shows that students from the lowest-income backgrounds, likely bound for two-year schools, file later than those who are wealthier and plan on attending four-year colleges.

In Texas and California, two of only a handful of states where FAFSA completion rates are up — though all those gains were made prior to mid-March — educators are struggling to guide students through the process from afar. Filing the FAFSA is challenging by itself, they say, and now nearly impossible with schools closed due to the coronavirus.

Sara Urquidez is executive director of the Academic Success Program, a community-based organization that provides college advising for 15 schools throughout the Dallas-Fort Worth area. She estimates that 30 percent of her 3,000 seniors have been asked to complete a FAFSA verification process that requires students to submit documentation to confirm the accuracy of their information. The vast majority of them are low-income.

“It’s not the family that has a two W-2’s and can use the IRS data retrieval tool,” she said. “It’s families that have complicated situations or have their own businesses where they make $7,000 a year.”

FAFSA completion is particularly burdensome for undocumented students or those whose families have mixed immigration status. According to the Pew Research Center, 13.4 percent of students in Texas and 12.3 percent of students in California have at least one parent who is undocumented.

Cifuentes said that parents who don’t have a Social Security number can’t sign their children’s FAFSA application electronically because it is required to get a PIN number.

They instead have to print out a signature page, sign it and mail it to the Department of Education’s Office of Federal Student Aid. “Many of our students struggle with just having technology and Wi-Fi at home, let alone a printer,” Cifuentes said.

Counselors in her district are having students upload a PDF signature page to a secure portal, printing it out for them, and then mailing the signature page along with a stamped envelope back to students so their parents can sign and mail it in. “A process that should just take a few minutes is now at least two weeks for our lowest-income families in the state,” Cifuentes said. “I worry for the students who do not have a counselor that can provide this type of support.”

Next year, Illinois and Texas will follow in Louisiana’s footsteps, requiring all graduating seniors to complete the FAFSA, or the state equivalent, starting in 2020-21. California, Michigan, Washington, D.C., and Indiana have been considering similar requirements. Several California districts have followed Val Verde’s lead and require it at the local level. Other states, including Tennessee (currently No. 1 in FAFSA completion), haven’t mandated it for graduation but do require it to access state aid programs.

Better-informed families

Christina Fontenot is director of college counseling at Abramson Sci Academy, a public charter high school in New Orleans. Her experience with the financial aid requirement is that it has raised awareness of college affordability. “I have a lot more conversations and presentations about financial aid with families, whereas previously the turnout would be a lot lower because it wasn’t required,” she said. “Now, parents and students are far more informed about how to pay for college.”

Fontenot said the financial aid requirement has been most helpful for students who plan to attend two-year schools. She’s seen an increase in the number who enroll directly in community college without taking significant time off after high school. “The students that … would have gone to four-year schools would have typically done the FAFSA anyway,” she said.

For student Claudia Martinez Alvarado, completing the FAFSA in order to graduate from Rancho Verde High School, one of four in the Val Verde Unified School District, was actually exciting. “College is very expensive, and I knew that filling out FAFSA would help me to create a pathway for me to afford college,” she said. “Having resources from the counselor really does help students out so much, especially me being first-generation and neither my family nor my siblings know anything about the college application process.”

Critics of the mandate are concerned it might prevent students from graduating, but advocates point to an opt-out process for families who can’t or don’t want to provide financial information.

Urquidez, though, worries about unintended consequences of mandating FAFSA completion, especially for undocumented students, as Texas implements the requirement for the Class of 2021.

“When you do it, you’re going to spend a lot of time chasing a metric … that’s going to take time away from students who need access to quality college advising,” she said. “There’s a lot of focus on pressing ‘submit’ and no focus whatsoever on what happens once you press it.”

“And as someone who is … responsible for guiding students through that process and [knows] the amount of time that it takes, I am concerned about the allocation of further resources and significant professional development for people who are responsible for this.”

School leaders who have experience with the mandate say support for counselors is essential, as are other efforts to promote college readiness. Mark LeNoir, assistant superintendent at Val Verde Unified, said he involves administrators, teachers, student government leaders and community partners to make sure the initiative is successful and doesn’t overwhelm counselors. They also bring in an immigration attorney to speak with families concerned about implications for their status. “One thing I did to support this process was to make sure we had whatever resources were needed to rally around our students and make sure their applications got completed,” he said. Because students in his district finished their FAFSAs early, he doesn’t anticipate a drop in completion rates.

Education leaders are also experimenting with other initiatives in light of the nationwide decline. For example, former U.S. education secretary Arne Duncan has teamed up with the nonprofit Chiefs for Change and the data management firm Data Insight Partners to launch a competition, challenging 20 school districts to boost FAFSA completion rates. School and district progress will be tracked on a digital platform.

In California, legislation requiring FAFSA for graduation stalled earlier this year, but advocates are still hopeful it will eventually pass. “Students and parents will need this support and assistance more than ever to help make postsecondary education attainable,” said Manny Rodriguez, senior legislative associate at Education Trust-West, one of the bill’s sponsors. “We are already hearing warnings from the nation’s financial aid administrators that coronavirus could severely impact applications — the impact on our undocumented/mixed-status families will be even greater — so this proposal is even more necessary.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)