A Turning Point for Union Research? New Study Shows a Negative Relationship Between Collective Bargaining & Boys’ Future Earnings, Career Tracks

The central factor at the heart of K-12 education in the United States, and all efforts to improve it, is the relationship between teacher and student. And since the majority of teachers are represented by unions — which bargain with districts over most of what happens within a school’s walls — the fate of America’s students will be determined in large part by questions of labor.

In ways both obvious and imperceptible, collective bargaining shapes almost everything a child experiences between first bell and the ride home: The curriculum they’re taught. The size of their class. How much their teachers make. How much their administrators make. Who stays. Who goes.

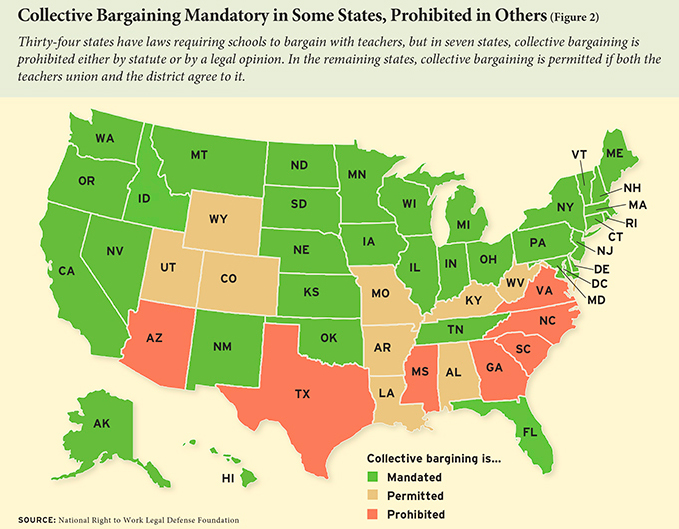

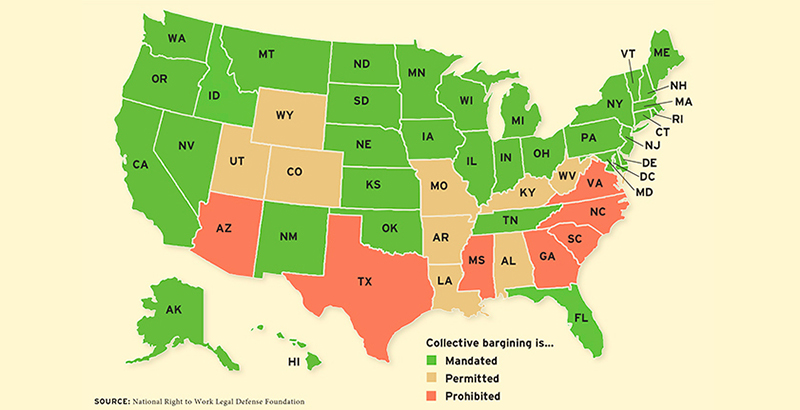

That’s why the influence of teachers unions is also the most politicized issue in education today. It’s why Republicans around the country have been whittling away at teachers’ collective bargaining rights for the better part of a decade, while Democrats do their best to defend them.

It’s why union foes have doggedly pursued their cause through high-stakes litigation — including the Janus v. AFSCME case, argued before the Supreme Court this winter, which could endanger the financial viability of many public-sector unions.

And it’s why some academic researchers spend their careers tracking organized labor’s impact on kids.

Cornell professor Michael Lovenheim is one such researcher, and the conclusions from one of his forthcoming papers could mark a turning point in our understanding of teachers unions. In a study of decades of economic data, he found that male students in states that mandate collective bargaining between school districts and teachers experience meaningful long-term reductions in their earnings and labor force participation. They cluster in lower-skilled occupations. And they demonstrate lower cognitive and noncognitive skills.

Overall, he estimates that the annual toll to the American economy could be as high as $150 billion.

The research was summarized in the journal Education Next in 2016 and discussed as part of a research session on teachers unions at the American Economic Association’s annual meeting in January. It is currently in the peer-review process for publication in an economics journal. With lawmakers in many states still aiming to pare back union protections, and with Janus looming as perhaps the greatest legal challenge organized labor has faced in decades, its findings could prove damning.

Although some previous studies have attempted to quantify the impact of teacher unionization on student outcomes, this is the first to examine its effects on former pupils midway through their careers. Lovenheim was asked in a recent interview with The 74 whether he was surprised at the scale of his findings.

“Yup,” he answered immediately. “I agree, the results are very striking. When Alex [fellow Cornell researcher Alexander Willen] and I came to this, we were very open-minded about what we might find, but we certainly didn’t have a strong prior belief that we were going to find these kinds of negative effects.”

Overall, male students exposed to 12 years of education in a state with a duty-to-bargain statute — a law requiring districts to bargain in good faith with a union elected by teachers — worked 0.52 fewer hours per week and saw their annual earnings decreased by $1,493, or roughly 2.75 percent. They were also 1.1 percentage points less likely to be employed.

Among historically disadvantaged subgroups, those figures were substantially worse: Black and Hispanic men earned $3,640 less per year, a 10.6 percent reduction. They were 2.6 percentage points less likely to be employed and worked an average of 1.35 fewer hours per week.

Those figures are alarming. But Lovenheim argued that they should be weighed against the value that collective bargaining provides to teachers in the form of influence and agency over their work environments.

“On the one hand, it’s true that teachers very much value collective bargaining, right? They’ll tell you that directly,” he said. “Can we retain some of the aspects of collective bargaining that teachers value while eliminating or significantly mitigating these negative effects? To me, that’s the policy question that comes out of this, and it’s one that we need a lot more study to answer.”

Data problems

Lovenheim’s study is best understood as an application of contemporary research methodologies to a question that has tantalized economists for decades.

Since the first economic studies into teacher unionization were published in the 1970s and ’80s, researchers have mainly focused on its influence over the more direct and tangible measure of total money allocated to public schools, and how that money is divided among teacher salaries, administrative costs, and classroom expenses. The existing research points to unions as a “rent-seeking” force in public finance, negotiating higher salaries and better working conditions for members without necessarily contributing to improved student performance, according to a 2015 review by Michigan State University professors Joshua Cowen and Katharine Strunk.

But it’s hard to capture the specific impact of unions for a few reasons. First, areas with unionized teachers tend to just be different from those without them. Of the 17 states that never passed duty-to-bargain laws, most are concentrated in the South, where higher rates of poverty and racial segregation impact student success in ways that make it difficult to pick out other possible factors.

The lack of historical data on students’ academic performance makes things even harder. Lovenheim and Willen’s study covers the period between 1960 and 1987, when duty-to-bargain laws were being passed. Compared to today’s testing and accountability regime, states and the federal government weren’t making any real effort to measure student achievement at that time. So researchers had to measure proxy effects like SAT results and high school dropout rates.

In his forthcoming study, Lovenheim instead uses data for American men ages 35–49 from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey to track how they performed once they proceeded from classrooms to the workforce. He focuses on men specifically, he says, because boys have been widely shown to be less resilient to economic shocks than girls.

Tracking community survey participants back to the areas in which they were born, he compared the difference in professional results for men from duty-to-bargain states (before and after the laws were passed) to the difference for men over the same period from states where such laws were never enacted. Since the nearly three-decade interval between 1960 and 1987 also saw huge shifts in social policy and educational practice, he also controlled for the presence of separate phenomena like school financing reforms, food stamps, and the Earned Income Tax Credit, which benefits workers with low to moderate incomes.

The conclusion was clear: The longer a boy received schooling in a state with a duty-to-bargain law, the lower his earnings and labor force participation.

Michigan State’s Strunk, who knows Lovenheim and has spoken with him about the study, said his findings represent the fruits of new methodologies developed over the past few decades that allow researchers to couple what had previously been wholly different troves of information.

Years ago, she said, economists necessarily trimmed their ambitions to match the constraints of available data.

“[The thinking was,] ‘I can track a kid from kindergarten through 12th grade, and if I’m real lucky, I can track a kid from kindergarten through college, if they go to a state school,’ ” she said. “What’s been happening in recent years … is they can track individuals from when they were in school into the workforce by linking different government data sets. And that’s a really powerful thing to do.”

What’s next

Both Strunk and Lovenheim agree that the study is cause for careful inquiry. Far from recommending sweeping policy changes to limit teachers unions, they insist that more research needs to be conducted into what specific mechanisms of collective bargaining might be generating these effects.

“People want to extrapolate from studies like Mike’s and say, ‘Well, giving unions the right to bargain causes X, Y, or Z, and therefore taking away those rights will cause the opposite,’ ” Strunk said. “But I don’t think we can extrapolate to that. I just think it’s a very different reform.”

“Unionization is probably here to stay. If we intend to make policy around it, we should think about what levers we should pull.”

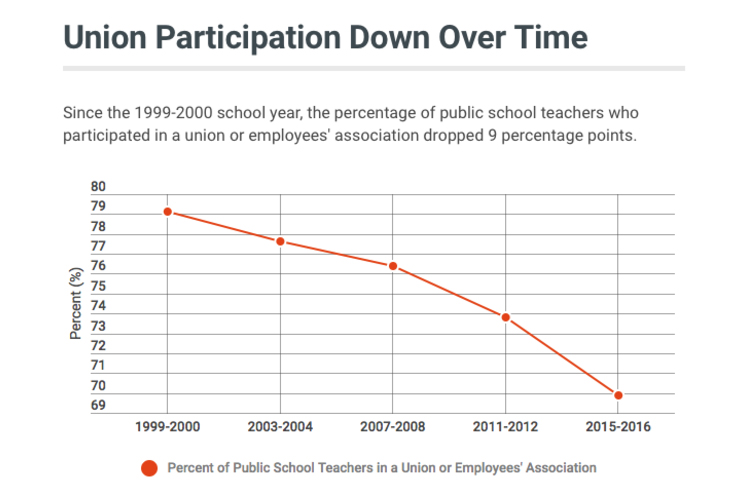

And yet since the 2010 elections elevated Republican governors and legislative majorities into statehouses across the country, unions have seen their rights to organize and charge de facto union dues suddenly limited. Studies of the aftermath, particularly in high-profile cases like Wisconsin, are beginning to show the results of those developments.

What’s more, even before the downturn in their political fortunes, unions had simply seen a steady decline in membership: In 1999, 79 percent of all public school teachers participated in a union or employees association. That number had already sunk to less than 74 percent a decade later.

Lovenheim acknowledged that the evidence he has uncovered is unflattering to teachers unions. “There’s no sugar-coating [that],” he said. “That’s absolutely the case.”

Nonetheless, he echoed Strunk’s note of caution.

“I don’t think the policy recommendation is necessarily, ‘Let’s outlaw collective bargaining,’ he said. “There’s more evidence being introduced on these questions, and so I think whenever we do policy, we want to take into account the body of evidence. We should never make policy based on one study.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)