Supreme Court Skeptical Biden Has Authority to Cancel Student Loan Debt

Observers say the issue could rest on whether the justices find states and borrowers had a right to sue.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Six states, two student loan borrowers and one advocacy group asked the U.S. Supreme Court to throw out President Joe Biden’s student debt relief plan, but much of the debate Tuesday on the two cases at issue centered on whether they had a right to sue in the first place.

Beyond the “standing” issue, however, conservative justices expressed skepticism that the administration had the authority to offer up to $20,000 in debt relief without going through Congress or at least allowing public comment.

“We take very seriously the idea of separation of powers, and that power should be divided to prevent its abuse,” Chief Justice John Roberts told Nebraska Solicitor General James Campbell, representing the states. “This is a case that presents extraordinarily serious important issues about the role of Congress and about the role that we should exercise.”

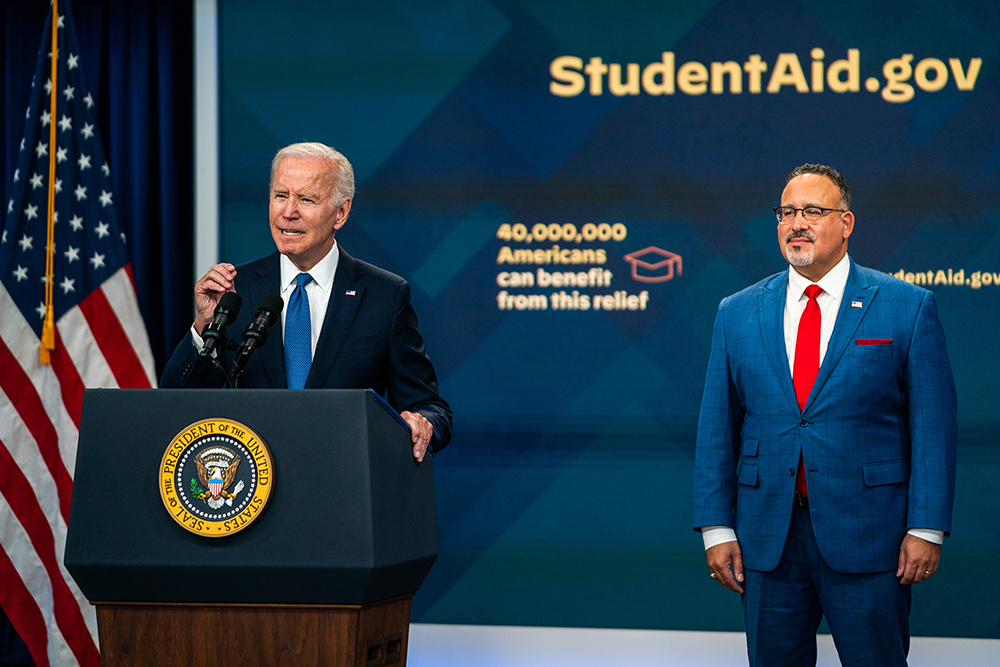

Those eligible for relief — roughly 40 million borrowers — have been left hanging since November, when a Trump-appointed federal judge halted the plan. Both the Trump and Biden administrations had argued that the secretary of education has the authority under a 2003 law, the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students, or HEROES, to forgive student debt because of the pandemic. COVID caused severe financial harm and increased the chances that borrowers would default on their loans, said U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar.

“Millions of Americans have struggled to pay rent, utilities, food, and many have been unable to pay their debts,” she said.

Biden’s plan offers $10,000 in relief to borrowers earning up to $125,000 and $20,000 for Pell Grant recipients.

‘A breathtaking power’

In the first case, Biden v. Nebraska, Prelogar argued that the six states had no right to sue on behalf of the Missouri Higher Education Loan Authority, the student loan servicer that would primarily be affected if students don’t make good on their debt.

Campbell argued that because the state created the nonprofit, it has an interest in the case and that if the authority loses revenue, it won’t be able to adequately contribute to the state’s higher education programs. On the merits of the case, he argued that the administration misinterpreted HEROES.

“The secretary here asserts a breathtaking power to do anything that he thinks might reduce the risk of borrowers defaulting,” Campbell said.

Justice Elena Kagan, one of the three liberals on the court, disagreed that Education Secretary Miguel Cardona was acting outside the intent of the law.

“Congress used its voice in enacting this piece of legislation,” she said. “Congress has authorized the use of executive power in an emergency situation.”

That’s what former Rep. George Miller of California, one of the authors of HEROES, wrote in an op-ed last week. He was among those who filed amicus briefs in support of loan forgiveness, saying the law’s use of the terms “waive” or “modify” in regard to the terms of a loan includes debt cancellation.

“Congress empowered officials to say that those requirements no longer apply — that borrowers no longer need to pay off the debt they owe,” he wrote. “And there’s no question that the COVID-19 pandemic is a ‘national emergency’ within the meaning of the law.”

In the second case, U.S. Department of Education v. Brown, attorney John Connolly, representing two borrowers and the conservative Job Creators Network Foundation, argued that Cardona should grant relief but should have used a different law — the Higher Education Act. That law would have required the department to seek comments from the public.

Congress, through HEROES, he said, “did not authorize the secretary to create a $400 billion debt forgiveness program behind closed doors with no public involvement.”

One of his clients, Myra Brown, is ineligible for the Biden program because she received loans from commercial lenders. Another, Alexander Taylor, qualifies for only $10,000 in relief because he’s not a Pell Grant recipient. Connolly said loan forgiveness is so important to the administration that Cardona would likely use the Higher Education Act to grant it if the current Biden plan were overruled.

But Prelogar said the case uses a “Rube Goldberg theory” and takes a “circuitous route” to get relief.

Even Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, a liberal, agreed.

“You … have to convince us that the administration would have provided this sort of debt relief under the authority you point to,” she told Connolly.

‘A technicality’

Observers said it’s possible that the court will never rule on the major question of whether the debt relief plan is an example of government overreach.

The administration has “staked a lot” on the idea that the plan will be upheld “on essentially a technicality rather than on this question of whether the Department of Education had the right to do this,” said Michael Brickman, an adjunct fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, who focuses on higher education.

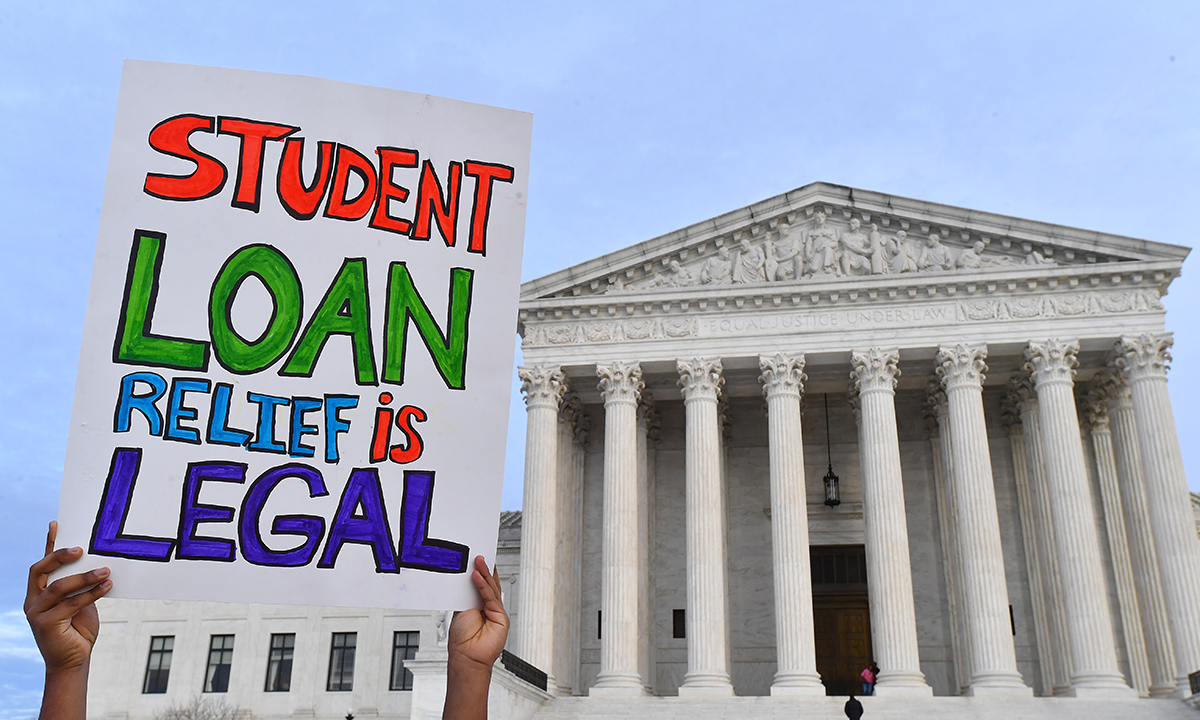

The arguments ran for over three hours, while demonstrators — overwhelmingly advocating for debt relief — amassed outside the court. About 100 college students with Rise, a nonprofit, had spent the night outside to get tickets to hear the arguments.

“We get caught up in the legalese — standing issues, statute issues — that we miss the big picture around the students’ lives who are going to be impacted by what the justices decide,” said Max Lubin, the organization’s founder. “Our job as advocates is to be prepared for every possible outcome.”

Among the 26 million borrowers who were automatically eligible for the relief or submitted an application are many K-12 and early childhood educators who needed more than a bachelor’s degree to meet job requirements and advance in their careers. That has consequences for students, some say.

Albert Sackey, principal of Hommocks Middle School in Larchmont, New York, said he knows teachers, principals and other administrators who are “strongly exploring changing career paths to everything from catering to real estate to law,” in part because of financial strain.

“We want to make sure that the people we are putting in front of our children have the necessary training and education that is needed,” said Sackey, who has two master’s degrees and a doctorate. “I graduated with my undergraduate degree in 1998 and have been paying significant student loans ever since.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)