New L.A. Schools Chief Carvalho Starts Monday With Immediate Challenge: College Readiness Among Black and Latino Students Has Plunged

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

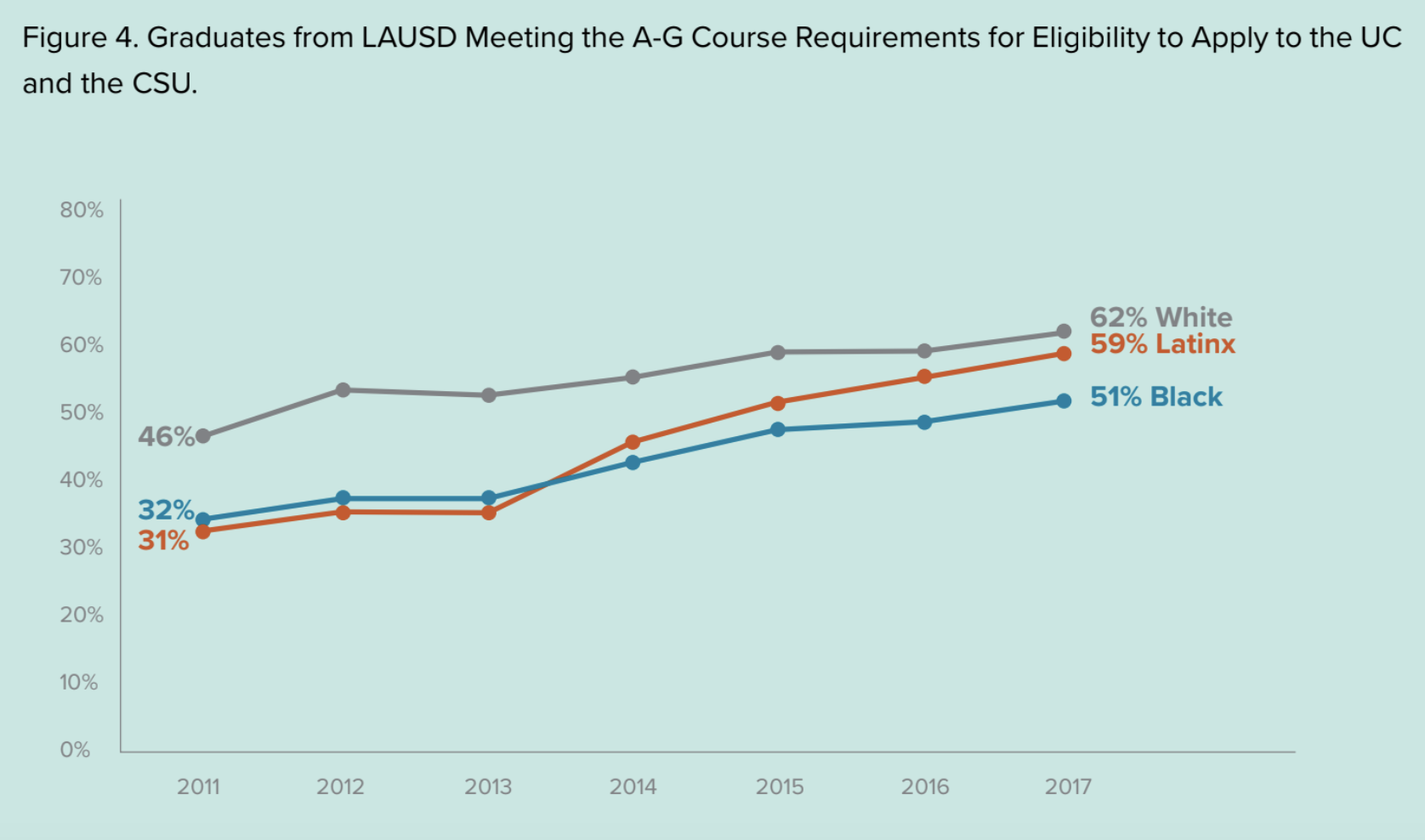

The percentage of Black and Latino students in Los Angeles schools completing courses that make them eligible to attend California’s state universities plunged in 2020, according to a report released Friday.

Before the pandemic, almost two-thirds of Latino and more than half of Black graduates from the Los Angeles Unified School District were completing the series of 15 courses required by both the University of California and California State University systems. In 2020, the rate fell to 54 percent for Latino students and 46 percent for Black students.

First-time enrollment in Los Angeles’s community colleges also saw a sharp decline — another indicator of the pandemic’s impact on students’ post-secondary plans.

“We can’t allow the pandemic to let us go backwards,” said Audrey Dow, senior vice president of the Los Angeles office for the Campaign for College Opportunity, which produced the report. “We all know that a bachelor’s degree, a college credential, is the new entry level into work.”

The district’s overall graduation rate reached 82 percent last school year, but that doesn’t mean students are well-prepared for college. The authors of the report commend the district for requiring students to take math, English and other courses needed for college admission in order to graduate. But they urge leaders to take the next step by requiring higher grades in those courses to get a diploma — a C instead of a D.

The findings contribute to the many challenges facing Alberto Carvalho as he prepares to take over as superintendent of the predominantly-Latino Los Angeles district on Monday.

“Los Angeles is ripe, is primed for rampant and rapid expansion of advanced academic opportunities for the students,” Carvalho said Thursday during a virtual event honoring him for improving college enrollment in Miami-Dade County Public Schools, where he was chief for 14 years. He’s the first to win Superintendent of the Year from the National Education Equity Lab, a nonprofit that brings courses from the nation’s top universities into high schools.

The Los Angeles district already has two schools working with the organization, but Carvalho said he plans to “forcefully” expand the model throughout the district. He said he’d also like to expand dual enrollment programs and work closer with colleges and universities, as he did in Miami-Dade, to have college professors teach high school and high school students attend college courses.

“If we simultaneously continue to lift the performance of Miami and we lift the performance of Los Angeles, America as a whole is elevated,” he said.

Carvalho’s track record in Miami — eliminating F schools in the district and increasing the graduation rate from less than 60 percent to 90 percent — is why the board recruited him and unanimously approved his contract, Jackie Goldberg, a member of the board, said last month when Carvalho was in town for his first school visit.

“He struck some chords that just seemed to ring the bell,” she said. “We don’t vote 7-0 on much of anything.”

Carvalho is under pressure to combat trends that have only worsened during the pandemic. Those include reversing declines in enrollment, narrowing persistent achievement gaps and, with over 18 percent of students chronically absent, increasing attendance.

“He is inheriting a district that, quite frankly, parents have lost a lot of faith in,” said Jay Artis-Wright, executive director of Parent Revolution, an advocacy group that was involved in a lawsuit related to reopening and now wants the district to provide more tutoring and individualized academic support. “There is a disconnect between the [learning] loss and the recovery that’s supposed to be happening right now.”

High school students are on a shorter timeline to make up for lost instruction before applying for college. This year’s juniors, she said, were in ninth grade when schools closed for the pandemic and might have missed out on opportunities to learn about financial aid and which courses to take.

The pandemic also “forced kids to make tough choices,” added Elmer Roldan, executive director of Communities In Schools of Los Angeles, part of a nationwide nonprofit that focuses on keeping low-income students on track toward graduation and college. High school students “felt the financial burdens” of their families, sometimes forcing them to work, delay college or choose a trade school as an alternative, he said.

But he agrees with the report’s recommendation that the district should increase the graduation requirement from a D to a C in those classes. That would make them eligible for admission to one of nine University of California or 23 California State University campuses.

“Now is the time, because there is money on the table” for counselors and other programs to help students prepare for college, Rodan said, adding that if there’s hesitation from teachers and administrators it’s because “you’re asking folks to raise the standards without providing additional resources.”

The class of 2016 was the first to be required to complete the classes for graduation. The Los Angeles school board set a goal of 75 percent of graduates earning a C or higher in those courses by 2026. But not requiring a C for graduation sends students the wrong message, Dow said.

“The whole impetus behind the policy change was so they could have a shot” at the UC or CSU systems, Dow said. “They are not going to be eligible applicants.”

According to the district, graduation requirements are not changing.

Raising the standard to a C is a worthy goal, said Ana Ponce of Great Public Schools Now, which funded the report. But she added that it could lead to a decline in graduation rates if too many students miss the C cutoff or “grade inflation” to ensure they make it.

Reforming remediation

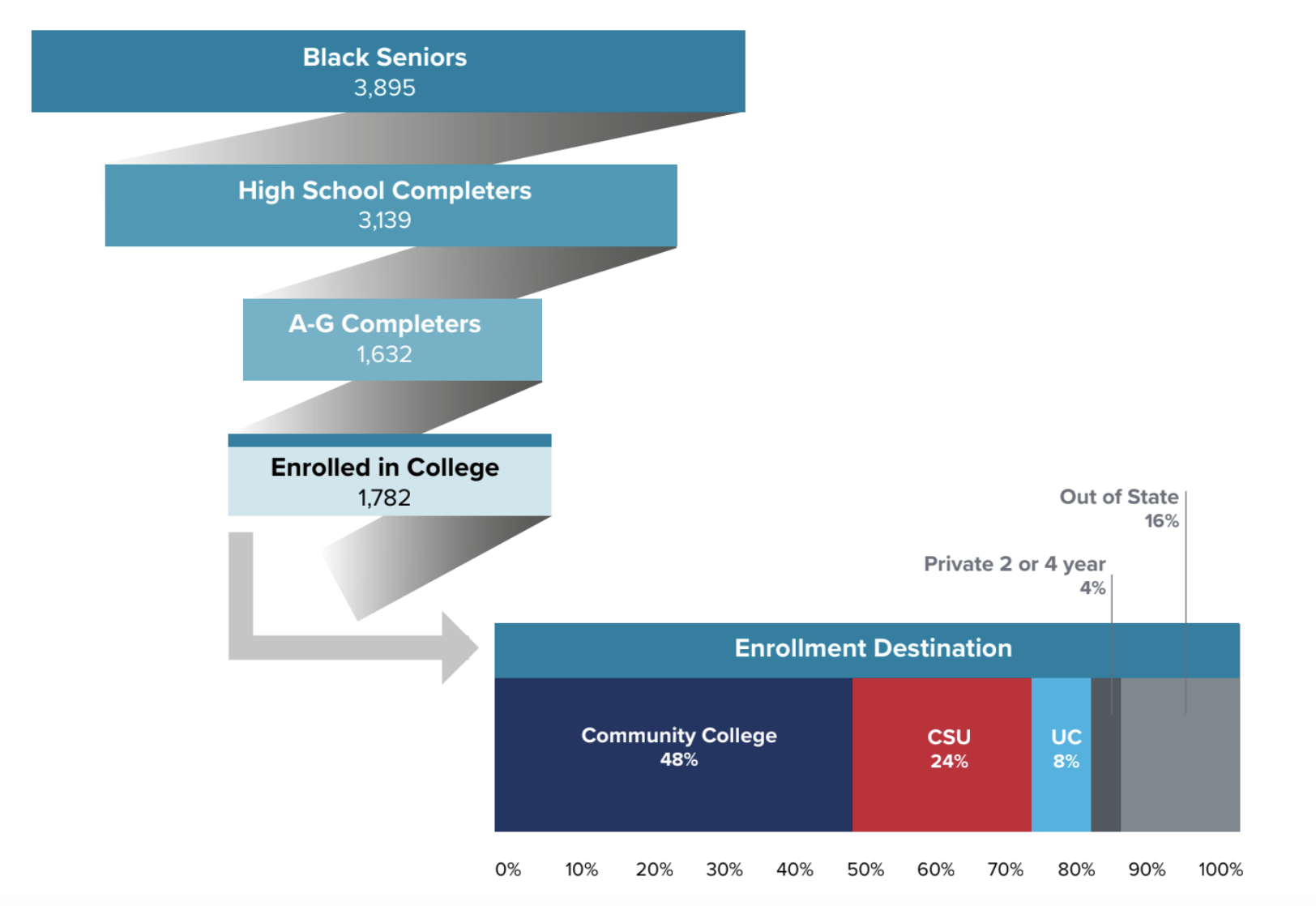

While the report focuses on getting more students into four-year universities, data shows that almost half of the Los Angeles district’s Black and Latino students who enroll in higher education attend community college. And once enrolled, they’re often placed in remedial courses that don’t contribute toward a degree. Those in remedial classes are also less likely to transfer to a four-year school, research shows.

In 2017, California passed a law to reduce the number of students in remedial courses. Community colleges must consider multiple factors throughout a student’s four years of high school, including grade point average, before deciding that the student is “highly unlikely” to pass a credit-bearing course.

But the Los Angeles Community College District’s nine campuses “have been slow to adopt and implement” those reforms, according to the new report. Three of the schools have reduced the number of remedial courses available in English, thereby placing more first-year students in college-level courses. But none has taken similar steps in math, the report said.

Less than 10 percent of Black and Latino students earn a degree or certificate within three years of enrolling in a Los Angeles community college, the report finds, and they are far less likely than white students to transfer to a four-year university within four years — 13 percent compared to 46 percent.

The report recommends community colleges place more students in transfer-eligible English and math courses during their first year.

One of Carvalho’s first steps, Dow said, should be forming a partnership with Francisco Rodriguez, the chancellor of the community college district, to address the report’s recommendations.

Of the 28,047 Latino students who graduated in 2021, 17,352 completed the required courses, and of those, 14,125 enrolled in college, the report shows.

“There has to be a focus from the district to ensure that students are enrolling in college,” Dow said. “What is happening to these students who aren’t going anywhere?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)