‘This is a Pressure Cooker’: A Third of Teachers Faced Abuse and Threats Last Year. Researchers Say Behavior Has Likely Gotten Worse

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A third of teachers faced verbal abuse or threats of violence from students and parents last school year and almost half were looking to leave their jobs, according to alarming data released last week. But how much worse are working conditions now?

The researchers who surveyed almost 15,000 school staff members on student behavior and toxic school environments plan to find out.

This week, the American Psychological Association launched a follow-up survey to keep tracking the extent of violence against school staff and its effect on educators’ decisions to stay in their jobs.

“This will give us strong comparisons across time,” said Susan McMahon, chair of the task force behind the survey and an associate dean in the College of Science and Health at DePaul University.

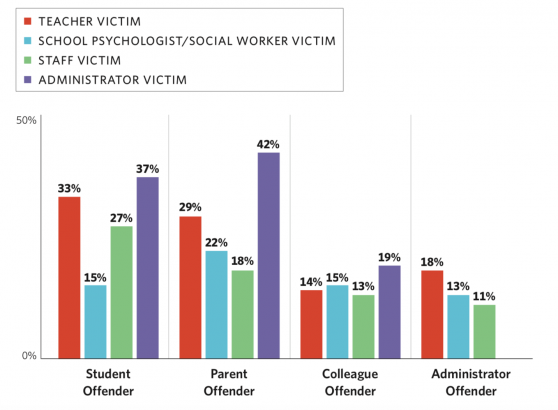

The current study showed 37 percent of administrators have been harassed or threatened with violence from a student, 42 percent have experienced similar treatment from a parent and 15 percent have been the victim of a violent incident involving a student.

Those findings reflect responses collected during the 2020-21 school year, when many schools remained closed. Recent reports from district leaders and professional organizations suggest schools are now seeing even more defiant and aggressive acts from students and that teachers aren’t waiting until the year is over to walk away.

“The fact that many schools were hybrid or online during the time of the survey makes these rates even more concerning,” McMahon said. “Not only are schools operating in person, the effects of the pandemic are extensive in terms of lost loved ones, lost learning, health issues and the stresses related to COVID-19.”

The results come weeks after President Joe Biden drew attention to student mental health as part of his State of the Union address and followed up by signing a federal budget that includes $111 million to increase the supply of school counselors, social workers and psychologists. The researchers point to federal legislation that would further increase both staff training in mental health and positions for those professionals. But they also say school climate has deteriorated and adding more staff alone won’t fix the problem. The researchers analyzed over 7,000 written responses, in which staff expressed the need for more security personnel and said they’ve faced “belittling” comments from parents and the community.

“We’re asking for more than just mental health money,” said Ron Astor, a public affairs and education professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, and a member of the task force. “This is a pressure cooker. We need clear guidelines around issues of civility.”

A February survey from the National Association of Secondary School Principals also pointed to rising concerns over harassment, with 34 percent of principals reporting online threats from parents and 29 percent reporting in-person threats from parents.

Elliot Duchon, a former superintendent in the Jurupa Unified School District, near Los Angeles, said political strife and escalating fights over masks and curriculum have contributed to a breakdown in school climate. In some districts, parents encouraged their children to go to school without masks before districts dropped mandates.

“Parents are literally teaching their kids to disobey school rules,” said Duchon, now a consultant with F3Law, a California firm specializing in education.

A look that ‘meant trouble’

Tracy Cooper, a veteran school bus driver in the Orange County Public Schools in Florida, who testified during a Thursday Congressional briefing on the survey findings, said a parent threatened to have her fired because she enforced the district’s mask policy.

“Luckily for me, I’ve only had one student threaten to physically attack me,” she said. A boy “had this look on his face that meant trouble” and then tried to push her down as she walked through the aisle, she said..

Maggie Maples, a recreational therapist in the Mustang Public Schools, near Tulsa, said she’s arrived at schools this year to work with students only to find they’ve been suspended.

“Eighth-grade boys can get a little violent,” said Maples. “There are a couple kiddos who are really defiant when it comes to agreeing with teachers. They cuss them out or make threatening comments.”

The data shows some educators have had enough. Researchers found between 23 percent and 43 percent of respondents wanted or planned to quit the profession. The rates across regions were fairly similar, ranging from 35 percent in the Midwest and West to 38 percent in the South. State-level surveys, including those in Mississippi and Texas, point to similar results.

Now a year later, local reports show some followed through on those intentions. In the Philadelphia School District, 169 teachers left between December and mid-February, and the Denver Public Schools lost more than 50 teachers shortly after the school year began. Experts, however, say it’s too soon to conclude that teachers are quitting at higher rates than in a typical year. A number of factors, including more open positions fueled by federal relief funds, could contribute to staff vacancies.

“We really are in the middle of a crisis right now,” said Autumn Rivera, a sixth grade science teacher from Colorado and one of four current finalists for national Teacher of the Year. “It’s very rare for teachers to leave in the middle of the school year.”

Not all schools are experiencing the same uptick in violent outbursts. Michael Brown, principal of Winters Mill High School in Carroll County, Maryland, north of Baltimore, said he braced himself for a rash of discipline issues last fall.

While there were a few “rough patches” around the holidays, that’s no different than a typical year, he said, adding that students seem to be grateful for school experiences that they missed while schools were closed. When the school held an outdoor homecoming dance, students stayed until the end despite occasional rain.

“It’s almost like a reintroduction to everything,” Brown said. “Just having the normal things that they had taken for granted has really helped to reduce some of those behaviors.”

Disclosure: Linda Jacobson co-authored several books with Ron Astor on students from military families and students facing school transitions.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)