Oklahoma Bets on School Counseling Corps to Address ‘Mental Health Deserts’

‘Our kiddos come from heavy trauma,’ one counselor said of the need for a $70 million investment in student mental health services

Nehemiah Woods hasn’t seen his dad in almost five years. They only talk once a month when the boy, now 11, phones his father, who is in prison.

But those calls take a toll. Afterwards, the fifth-grader frequently turns defiant and impulsive. He hurls insults at classmates attending his school near Oklahoma City.

That began to change last fall, when the Mustang Public Schools hired Maggie Maples, a recreational therapist who uses games and art to help children with emotional problems.

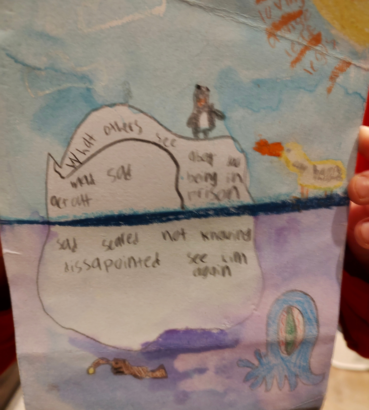

Maples had Nehemiah draw a picture of an iceberg to help him visualize the deep feelings beneath his outward behavior. They’ve worked on puzzles to improve concentration and made slime to practice following directions.

“Maggie has helped him to surface some of those emotions that he didn’t know existed,” said Jessica Maxwell, his mother. “He’s more open to talking to someone who is not mom.”

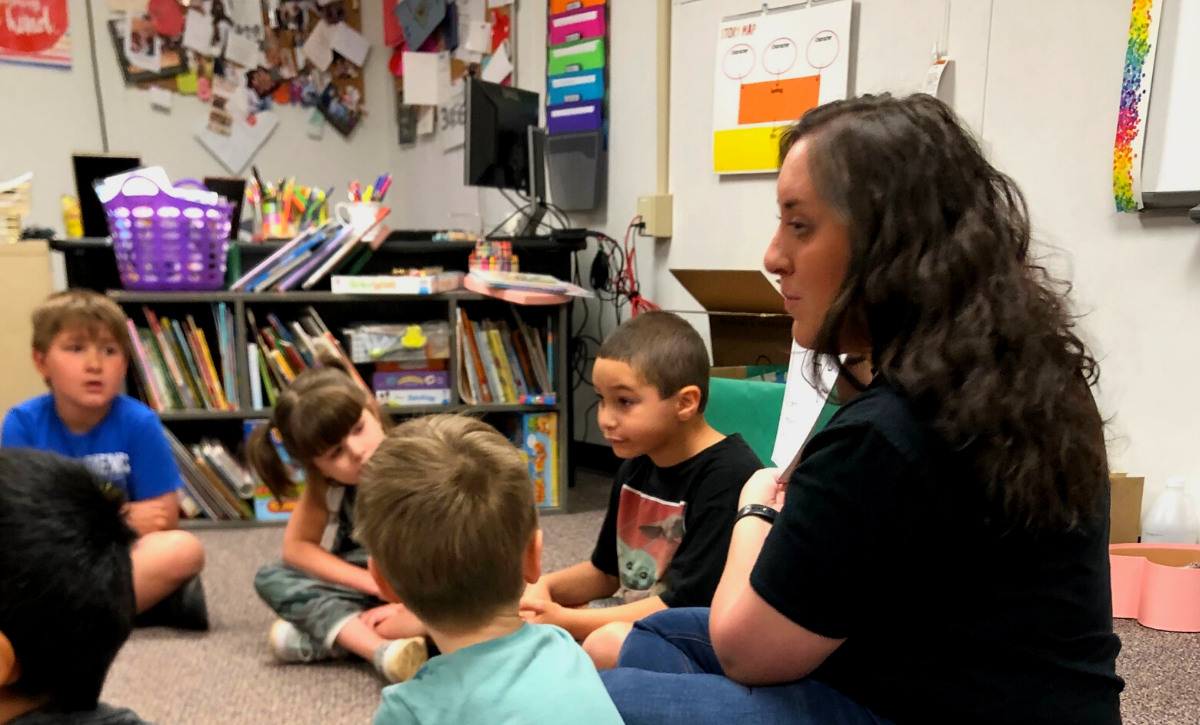

Maples is part of the Oklahoma Counseling Corps, a new effort to increase the number of mental health professionals in Oklahoma schools. She sees children individually and serves groups of students “who can’t make it through a typical school day,” she said.

The new grant program aims to fill a void in a state where the counselor-to-student ratio far exceeds the 1-to-250 goal set by the American School Counselor Association. The average school counselor in the state is responsible for almost 400 students. Caseloads in some states are even larger — as high as 716 students in Arizona and 665 in Illinois.

Prior to the pandemic, the state legislature repeatedly rebuffed state Superintendent Joy Hofmeister’s request for $58 million to hire 1,000 new counselors.

“It’s been five years of trying to bring greater awareness to the way our children have really suffered,” said Hofmeister, a Democrat who is running for governor this year. “When the relief dollars came, we knew exactly what we wanted to do.”

The state put $35 million in American Rescue Plan funds toward hiring 300 counselors and other mental health professionals, with 181 districts matching it with another $35 million.

A recent state-by-state “report card” on school mental health showed that of the 54,000 students in Oklahoma with major depression, 30,000 don’t receive any treatment. Meanwhile, many counselors, who often have teaching credentials, have been reassigned to cover classroom shortages.

Oklahoma educators, like their colleagues across the country, say more students this year have needs that require attention from mental health specialists, including depression, anxiety and thoughts of suicide.

But on Tuesday, the National Center for Education Statistics released data showing that around half of schools surveyed nationally — 56% — say they are equipped to provide mental health services to students who need them. Schools cited large caseloads, a lack of licensed professionals and inadequate funding as the primary obstacles.

Meanwhile, many teachers say they face resistance from students who had less structure during school closures and quarantines.

“Students’ needs have really changed,” Maples said. “You asked the kids to be flexible for two years, and then you have to have some flexibility when they come back.”

The Calm Waters Center for Children and Families trains school counselors and teachers to better understand how the grief that comes with having a parent in prison or losing a family member to COVID affects children. The center offers free support groups to over 80 Oklahoma City-area schools, said Erin Engelke, executive director, adding that the number of groups has tripled in the past year, with many children of incarcerated parents among the participants.

Oklahoma has the highest incarceration rate in the nation and an abundance of what Hofmeister called “mental health deserts.” Roughly 30,000 children in the state each year have a parent in prison.

Those children often isolate themselves because they feel shame and don’t have appropriate ways to express anger, said Hannah Showalter, assistant program director at Calm Waters. Children in the support groups learn yoga, breathing exercises and mantras — like “I’m not alone” and “It’s not my fault.” They pretend their words are “shame spray” to chase away the “shame monsters,” she said.

‘Heavy trauma’

Letisha LeBlanc, formerly a mental health specialist for a youth services agency, used to see some of those children when the Okmulgee Public Schools, south of Tulsa, referred them for therapy. Prior to the state grant, the district didn’t have elementary counselors. Now LeBlanc works for the district, talking to students on the playground and greeting them in the hallways.

“Our kiddos come from heavy trauma,” LeBlanc said. Nine have lost a parent this year. Many live with grandparents, have witnessed domestic violence and suffer from chronic neglect.

LeBlanc lets students know she’s available to talk before negative feelings fester.

Funding for the Counseling Corps is temporary, making the initiative a bit risky. Using relief funds to hire staff is exactly what school finance experts advise districts not to do.When funds dry up, positions that schools have come to depend on are often cut.

Hofmeister is taking a gamble. She hopes the grant program will be effective enough to convince lawmakers to continue paying for the positions when relief funds run out in two years.

“We will have a nice set of data for the legislature to show a high return on investment,” she said. “This is something that they need to continue to help us support.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)