Teachers Unions Say They Need More COVID Tests Before Reopening Classrooms. But Experts Are Warning About the Limitations, Expense and Tradeoffs in Focusing on Swabs

For anxious teachers nationwide pushing for widespread COVID-19 testing before they return to the classroom, Los Angeles Unified Superintendent Austin Beutner believes he has the answer.

The district has tested roughly 400,000 staff members, students and their families for the coronavirus since September, using a Microsoft-developed website that tallies positive cases and thoroughly tracks whether contacts have been traced. The program involves three universities, two health care companies and a pair of labs — one of which sold Beutner on its ability to return results by 5 a.m. each morning.

“We think we’ve built a system that is as complete as we know,” said Beutner, an early convert to the notion of testing as the route to reopening schools. “If we know more than half the people who have the virus have no symptoms, why would you not test?”

But there’s a hitch. Despite the sophisticated regimen — embraced by the teachers union and expected to cost $150 million — schools in Los Angeles still haven’t reopened. Countywide case rates haven’t fallen to an acceptable level.

Los Angeles Unified’s approach is what many teachers across the country are clamoring for. And with President Joe Biden in office, they now have the political support they’ve wanted in Washington for a major investment in reopening schools. But locally, disagreements between unions and education officials over the extent of COVID-19 testing — and in some cases, vaccines — are derailing plans to bring students back. In Chicago, the nation’s third largest district, teachers are on the brink of a strike after voting to reject in-person learning. The standoffs could imperil Biden’s promise to open most K-8 schools within the first 100 days of his administration.

Reliable and frequent testing is expensive and, many researchers say, unnecessary: While the data is useful, schools have safely opened without it. Biden, however, appeared to side with Chicago teachers earlier this week.

“We need testing for teachers, as well as students,” he said. “We should be able to open up every … school, kindergarten through eighth grade, if, in fact, we administer these tests.”

Chicago teachers are not alone. Unions in New Jersey and Fairfax County, Virginia, also plan to hold out for more extensive measures. But as Los Angeles demonstrates, testing is often not enough. A continued post-holiday surge in cases, propelled by a new and more virulent COVID strain, is fueling the pushback at a time when teachers have lost over an estimated 530 of their own to the pandemic.

While not dismissing their concerns, some experts say the unions are shifting the goalposts of what constitutes a “safe” reopening.

“If the unions felt this strongly that testing was so important, that’s what they should have been putting forward back in September,” said John Bailey, a fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute who writes extensively about the pandemics’ impact on schools. “This isn’t following the science. This is following the politics.”

Testing is not mitigation

As it strives to take control of pandemic response in its early days, the administration sent conflicting signals this week. While Biden supported Chicago teachers’ calls for testing, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a paper concluding there is “little evidence that schools have contributed meaningfully to increased community transmission” as long as they were vigilant about other safety practices.

Bailey said the conflict reflects a misunderstanding over the purpose of testing.

“Testing by itself is not mitigation,” he said. “Testing is one more layer to risk mitigation.”

Dr. Kanecia Zimmerman, an associate professor of pediatrics at Duke University whose research was cited in the CDC paper, added that there can be downsides to widespread testing. One is creating a false sense of security that could lead students and staff to ease up on more basic cleanup procedures like wearing masks and washing their hands.

Other unintended consequences, she said, can result if a student from a low-income family tests positive. The family would have to quarantine and parents might not be able to work. Beutner noted that he’s facing such resistance from Los Angeles families opting not to test because they don’t want to know the results.

“While I wholeheartedly believe in testing in general and its importance, the availability of a testing kit merely scratches the surface of what’s needed here,” Zimmerman said. “Testing alone won’t stop spread. Benefits and harms of testing must be considered.”

‘Carefully and slowly’

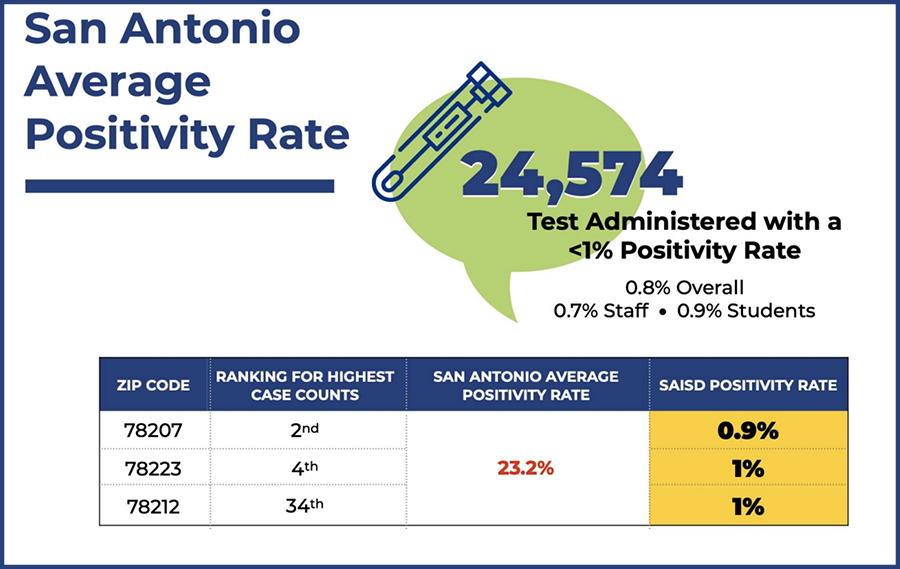

In Texas, where districts must give families the option to keep their children in school, the San Antonio Independent School District was among the first to reopen. About 30 percent of the district’s roughly 49,000 students now attend in person.

When schools reopened after Labor Day, testing wasn’t broadly available. The district initially tested adults, high school students and those in afterschool programs using what is known as a “rapid” test — fast and affordable at about $5 each, but not always reliable. Through a partnership between the state and a nonprofit, the district now offers PCR testing — a more accurate nasal or throat swab that detects the virus’s genetic material.

The weekly tests are optional, but among those who have taken them, the results show less than a 1 percent positivity rate. District spokeswoman Vanessa Barry said there’s still some pushback from teachers who prefer all learning be virtual, but “we’re doing everything we can.”

Emily Oster, a Brown University economics professor, works with education groups to manage a national COVID-19 school tracker. She’s a strong proponent of increased testing — if for no other purpose than to build trust among teachers.

“A huge reason to do this is that it will help people feel more comfortable and confident at school,” said Oster, who is tested twice a week at Brown and takes her children weekly to a drive-in testing facility at the Roger Williams Zoo in Providence. The clinic texts her the results by the time she gets home. “No one wants people back at school being anxious.”

But putting off in-person learning until both staff and students are vaccinated — as a Fairfax Education Association leader suggested — is “a very unfortunate position,” Oster said. Reaching that level of protection against the disease might not happen until 2022.

Eileen Chollet, the parent of a special needs student in the Fairfax district, agrees.

Her daughter Caroline Ma, who has speech, intellectual, coordination and other needs, attended school in person for 22 days last fall, but doesn’t learn well in front of a screen. Her case is one of several that sparked the U.S. Department of Education to investigate whether districts are providing appropriate services for special needs students while school buildings are closed.

Chollet also happens to be a scientist who conducts COVID-19 risk analysis. So she has some opinions on the value of testing.

“A COVID screening swab once a week is just not very effective,” she said. “But I’m for it if it makes the teachers feel better.”

Meanwhile, some union leaders say they’ve been blindsided by politicians’ moves to return to school. That happened in New Mexico this week when Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham said in a virtual State of the State address that schools will begin reopening Feb. 8.

Albuquerque Federation of Teachers President Ellen Bernstein calls that premature. “We’re trying really hard to avoid the open, close, open, close, open, close,” she said. “Doing it carefully and slowly is better.”

That political push-pull is likely to spread now that legislatures are back in session. In Iowa Thursday, lawmakers passed a bill requiring districts to offer families the option to send their children to school.

‘Building the ladder’

As districts struggle to reopen, the type of coronavirus testing they conduct might become an obstacle. Scope and frequency matter. Beutner described random sampling as merely “testing the mood,” and Zimmerman said a “scientifically sound” program in schools would require testing everyone multiple times a week.

American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten outlined the plan she’d like to see in an op-ed this week with Dr. Rajiv Shah, president of the Rockefeller Foundation, a nonprofit that addresses global issues like disease and famine. They argued that “robust” testing is the key to reopening schools before a vaccine becomes widely available. The foundation’s plan calls for testing 300 million students per month.

But such an initiative would carry a huge cost. Weingarten and Shah estimated testing for the spring semester at roughly $22.7 billion. But they didn’t identify who should pay for it.

The federal relief bill passed in December gives Title I schools $54 billion, or roughly $1,000 per student. With PCR tests costing around $30 each, a weekly program would quickly eat up those funds, said Georgetown University’s Marguerite Roza, a guru to districts hoping to stretch their federal dollars as far as possible. Biden’s pandemic recovery proposal includes $130 billion for reopening, as well as an additional $50 billion for testing frontline workers, including teachers.

Deborah Gist, superintendent of the Tulsa Public Schools in Oklahoma, hopes the plan makes it through Congress. The district is part of a Rockefeller Foundation pilot program that funds rapid tests. Supply is a problem, however. The district plans to open schools in mid-March, but would only have enough tests to last about six weeks.

“We very strongly believe that a system of regular rapid testing to preemptively identify exposure is the best way to have in-person instruction,” Gist said. Those who turn up positive are referred for a PCR test.

But Roza argues it’s unwise for districts to spend most of their relief funds this way. Due to its expense, testing has the potential to draw scarce funds away from addressing the chief educational outcome of the pandemic: learning loss at a staggering scale. Experts have predicted — and some districts are reporting — that students are as much as a year behind where they would have been in reading and math had the pandemic not occurred.

Roza thinks Weingarten’s proposed $22.7 billion, for example, might be better spent on students’ academic futures. She suggests a “parting gift” of $10,000 to graduating seniors toward their first year in a public college or university so they won’t take on debt.

To her, districts fall into two categories. Open districts are “so much further along” in addressing learning loss, she said, naming Superintendent Pedro Martinez of the San Antonio district as an example.

“The other ones are still digging their hole and getting deeper and deeper,” she said, “and he’s already building the ladder to get out.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)